A few hundred years ago, only the wealthy and adventurous indulged in leisure travel. A generally uninteresting Englishman of the 1770s who went to Florence and wrote an account of the experience could expect his boring book to be a massive success. Nowadays, I doubt he’d get over a dozen email list subscriptions.

Today, well over a billion people travel internationally every year. The general growth of the middle class and improvements in transportation are huge parts of this, but another factor is the invention of commercial travel packages. We owe this to one man: a woodturner turned temperance activist turned commercial tourism tycoon named Thomas Cook.

A modern Thomas Cook shop in Belgium. Photo: Shutterstock

Spreading the good word (by train)

Born in Derbyshire in 1808, Thomas Cook left school at the age of ten to work, first as a gardener and then as a woodturner. He hated woodturning, apparently, and pivoted again to work in a printer’s shop. It was his work there, printing books for the General Baptist Association, which led to his induction in the Baptist movement, specifically the fight for temperance.

By age 20, Cook changed careers again, becoming a Bible reader and missionary for the Association of Baptists. Over the next year, he later recalled, he walked over 3,000 kilometers, trying to convince people to stop drinking alcohol. In 1841, he realized that walking was slow. He could convince people not to drink so much faster by train.

By then, he was high up in the South Midland Temperance Association. He was also the founder of the presumably beloved-by-children Children’s Temperance Magazine. With this resumé, he approached the Midland Counties Railway Company and organized a special train charter to bring Leicester Temperance Society members to a meeting in Loughborough.

That train left Leicester’s Campbell Street Station bound for Loughborough on July 5, 1841. Nearly 500 passengers paid one shilling to hop on board. Also on the train was Cook’s seven-year-old son, John Mason Cook, who will be important later. A marching band and cheering crowds greeted their arrival. And that, history generally agrees, was the first publicly advertised special railway excursion.

This sounds mean, but I think there’s something a little scary about this picture of Thomas Cook. I can’t put my finger on it, but something is definitely off, perhaps behind the eyes. Photo: The Thomas Cook Archive

From humble beginnings to Great Exhibitions

The first train venture was such a rousing success that Cook soon began organizing them on a regular basis. By 1845, he had officially moved to Leicester and took up organizing railway trips as a career.

They were still small-scale, local trips, but Cook was already demonstrating a gift for travel innovation. Remembering his time as a printer, he began printing trip handbooks. He was also contracting with hotels along the way, issuing hotel tickets which became a familiar standard of late 19th and early 20th-century travel.

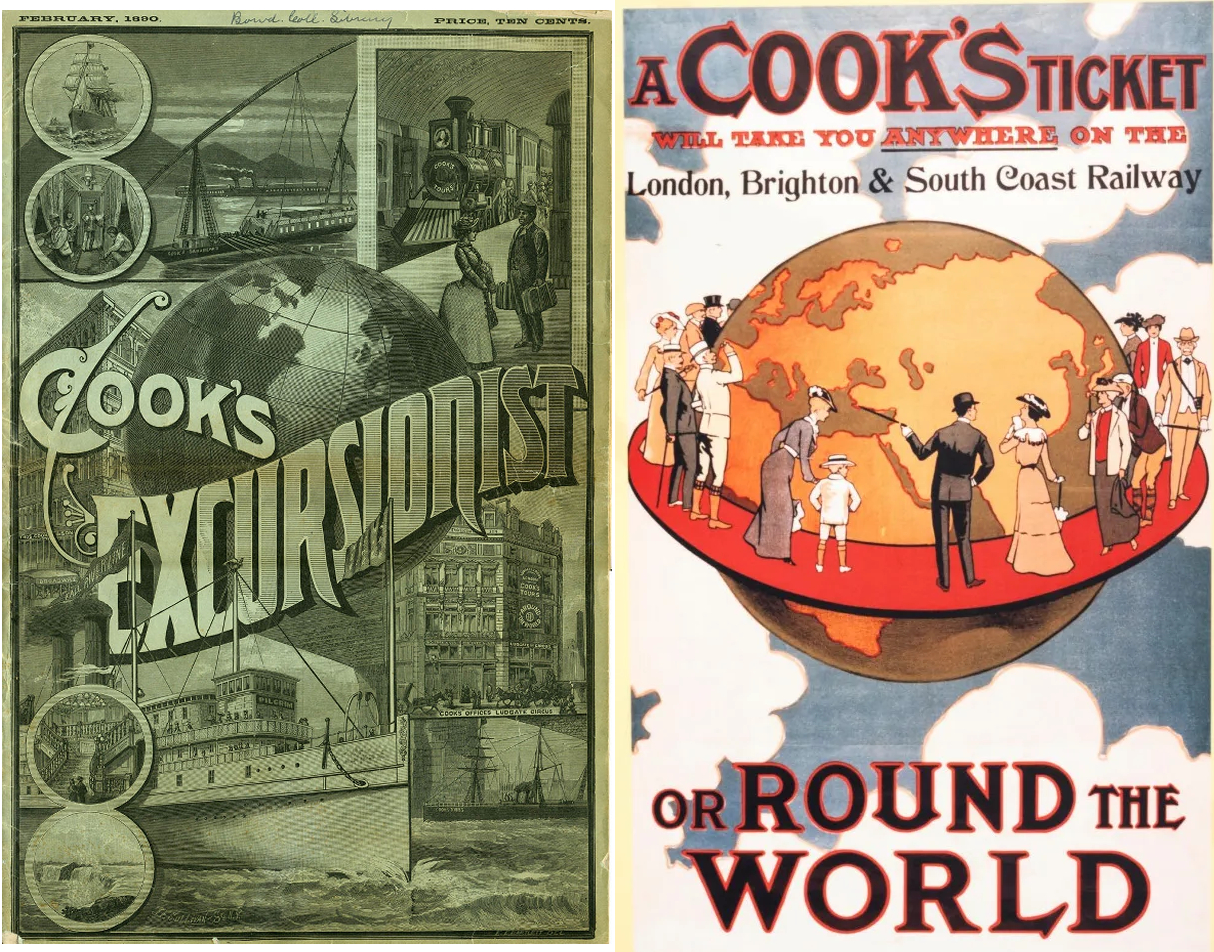

In the late 1840s, Cook began publishing his magazine, called The Excursionist, and planned to expand his trips outside Britain. In 1850, Crystal Palace architect Sir Joseph Paxton contracted Cook to organize the transport of workers, and then visitors, to London’s Grand Exhibition. By the end of the Exhibition, Cook had arranged the transportation of over 150,000 people.

Four years later, when the Exhibition was in Paris, Cook organized trips from Leicester to Calais. Cook’s energy and ambition were impressive, and every year his excursions went farther, and his name became more and more like a byword for “travel.”

Left, the cover of an issue of Cook’s ‘Excursionist.’ Right, an Edwardian era poster for the Thomas Cook travel agency. Photo: Thomas Cook Archive

Thomas Cook and Son

Thomas Cook seemed to have a genuine passion for travel. In the early years, he personally led many tours. As his company expanded, he acted as both scout and advertiser for new tours. In 1872, Cook went on a 222-day tour of the world, writing letters back to The Times. Two years later, he invented the traveler’s check, which I’m assured is something our older readers will recognize.

Of course, when the owner of a company is galavanting about the globe, that doesn’t leave much time to actually run the business. By the 1860s, that honor fell to his son, John Mason. The younger Cook was raised in the chaos of his father’s emerging rail travel empire. While Thomas loved travel, his son had a keen head for business. In 1864, he became an official partner, and the company became Thomas Cook and Son.

John Mason and his father seemed to have a contentious relationship about how the company should be run. By 1878, John Mason had won the tussle, and Thomas departed with a fixed pension. He used this to build a number of coffeehouses in Leicester. Meanwhile, John Mason turned to aggressive expansion, contracting with more railroad companies.

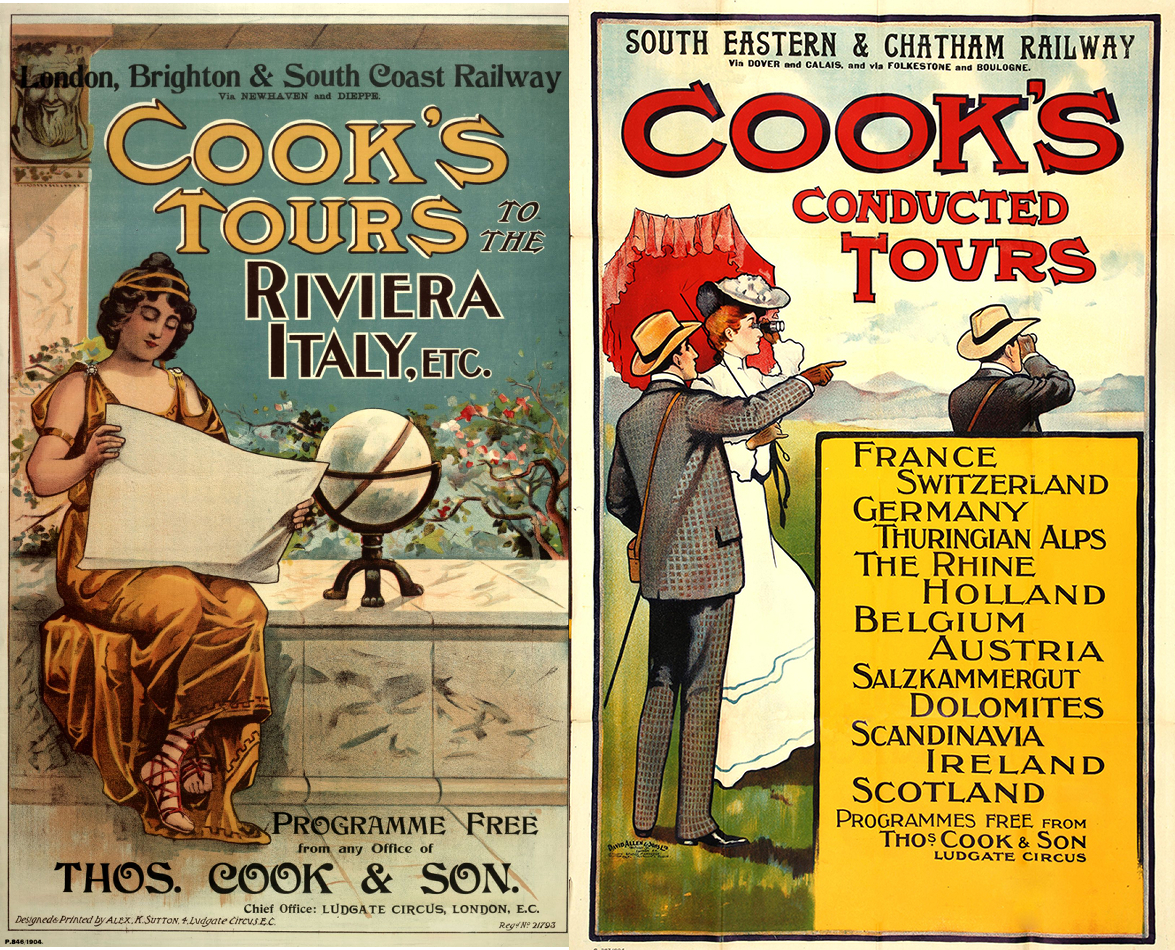

Cooks’ Tour posters from the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. Photo: Thomas Cook Archive

Let’s take a Cook’s Tour

What would it be like to take one of the Thomas Cook company’s tours at their heyday, at the end of the 19th century? Let’s take a look at one of their most popular and widely advertised tours in this period, a trip to Egypt.

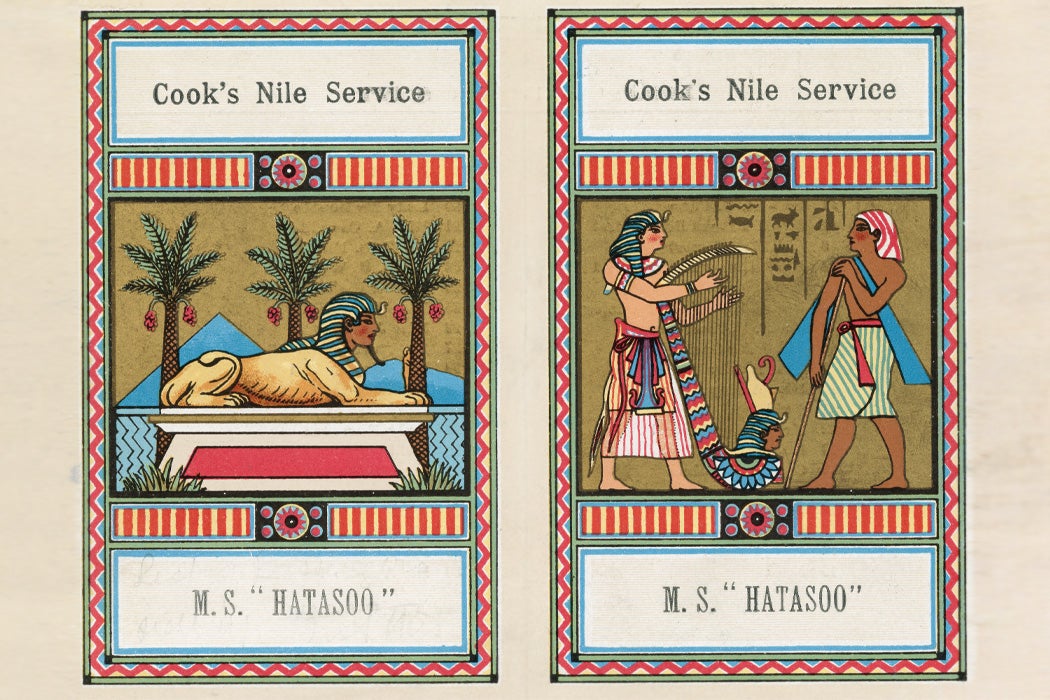

The first Cook’s Tours to Egypt arrived in 1869, led by Thomas Cook himself. By 1880, Egypt was a British holding, and Cook’s company held absolute rights over river travel on the Nile. Evolution in transport technology meant Cook’s could offer a 20-day Nile excursion on a luxurious steam paddleboat, instead of the three-month-long dahabiyyah sailboat journey.

The standard Cook’s Tour of Egypt in the 1890s did not include fare to Egypt. Rather, tourists made their own way to Alexandria and then went to the Thomas Cook and Son office to book their Nile tour. These cost £50, or £60 for a larger berth. Armed with their Cook’s Handbook for Egypt and Sudan (written in part by the curator of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum), the passengers boarded one of the company’s Nile fleet steamers.

The passengers were conveyed down the Nile on floating hotels, stopping on the shore for excursions to famous monuments. Local laborers waited on shore to carry them in sedan chairs. The guidebook advised that one was not to tip them unless they’d really gone above and beyond, because they were greedy and lazy by nature. Awesome.

The Rameses III, built for Cook in Scotland, could hold 80 passengers. Photo: 1893 Thomas Cook and Son album

The dark side of Thomas Cook

It’s perhaps no surprise that a company founded by a missionary, whose guidebook recommended treating an Egyptian “with a kind but firm hand, as if he were a child,” would be aligned with violent Imperial interests.

As the British Empire expanded, Thomas Cook’s company expanded with it. The relationship was mutually beneficial. Imperial occupation meant the company could offer safer, cheaper tours, massaging local regulations, and acquiring whole ports as well as hotels, rail lines, and waterway rights. Thomas Cook and Son, in turn, provided material and logistical support to Imperial efforts.

In 1882, Thomas Cook fleets transported British occupation troops into Egypt, and carried the wounded out after the battle of Tel al-Kabir. In 1884, the company moved 18,000 troops, 130,000 tons of supplies, 800 whaleboats, and upwards of 60,000 tons of coal from Asyut, where the railway ended, to Wadi Halfa. These troops were being sent to break the Siege of Khartoum, Sudan, then a British holding via Egypt.

The company’s publications also served as mouthpieces for British Imperial propaganda, with articles extolling the civilizing benefits of British occupation in Palestine. In India, Thomas Cook and Son were given exclusive rights to sell tours to Mecca. They also created detailed maps of Bombay for use by the British rulers.

Cook controlled the Nile, and therefore, travel through the entire region. Photo: Thomas Cook Archive

The birth of commercial travel

It may be hard to understand today, when technology has left things like the traveler’s checks, hotel tickets, and to some extent, the whole idea of a package holiday behind. But for the emerging Western middle classes, Cook’s Tours invented and then dominated the very concept of commercial travel.

Thomas Cook died in 1892. His funeral was attended by “the Baptist Union, the Baptist Missionary Society, the National Temperance League, all the great railway companies…various local bodies, [and] upwards of 1,000 mourners,” as well as the mayor of Leicester.

In 1899, John Mason Cook died of dysentery contracted while escorting the Kaiser on a £50,000 tour of the Holy Land. I can only imagine this is how he would have wanted to go.

Thomas Cook’s statue has stood in Leicester since the early 1990s. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Cook in the 21st century?

The business stayed in the family until 1928, and remained prominent over the next few decades. But by the 1950s, newer, cheaper options were emerging. Cook had always sold luxury, and the people wanted the cheapest.

Though Thomas Cook survived the early 1970s recession, it was already shutting down divisions and selling off property. Over the next few decades, it was sold off to one owner after another.

A glimpse at www.thomascook.com in the year 1998. I miss when websites looked like this. Photo: Screenshot (site archived via Wayback Machine)

In 2016, the company celebrated its 175 anniversary. The festivities included actors in period clothing at the Leicester railway station, which sold tickets for one shilling. The choice to mark this date, instead of waiting for 200, indicates that perhaps everyone suspected it would not make it that long.

In September 2019, the company collapsed dramatically. Having failed to secure needed rescue funding, it shuttered without warning. Over 150,000 British customers currently on a Thomas Cook tour were stranded abroad, necessitating the largest peacetime repatriation effort in British history.

Planes were grounded, hotel guests were prevented from leaving, it was a whole thing. It probably drove at least a few stranded vacationers to drink, which, ironically, Thomas Cook would have really hated.