Most readers will not be familiar with the Ashat Wall in the Gissaro-Alai, and that’s not surprising. It’s in a remote part of Kyrgyzstan that is rarely visited by climbers. But Olga Lukashenko, Anastasia Kozlova, and Darya Serupova of Russia have just spent three weeks on its sheer granite faces.

The all-female team was alone on the wall, climbing onsight and in harsh conditions, with only one person waiting for them in base camp. Only elite male alpinists had attempted it before, said Olga Lukashenko.

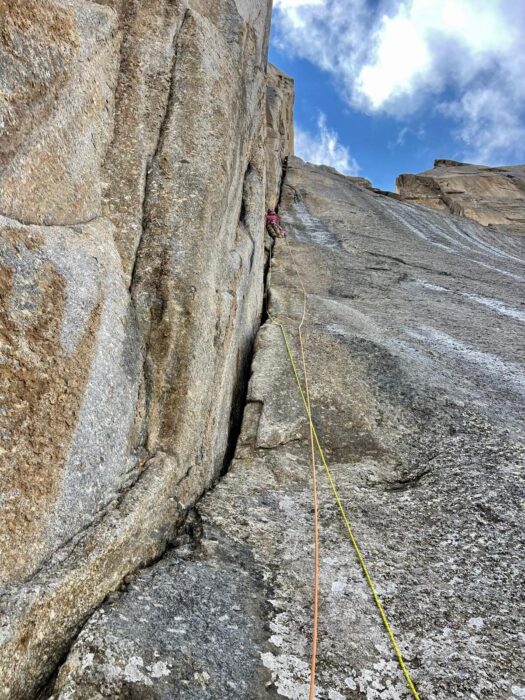

A sunny day during the expedition. Photo: Olga Lukashenko

An added thrill

Lukashenko had long been captivated by 5,282m Sabakh Peak, the highest summit on the Ashat Wall. When she discovered that only elite male alpinists had ventured here before, it further stoked her interest.

“Frankly, I don’t really care about the difference between male and female climbers,” she explained. “I’m just highlighting that this climbing area is genuinely serious and challenging. This discovery [that no women had previously attempted it] only added to the thrill of tackling such an uncharted and demanding climb.”

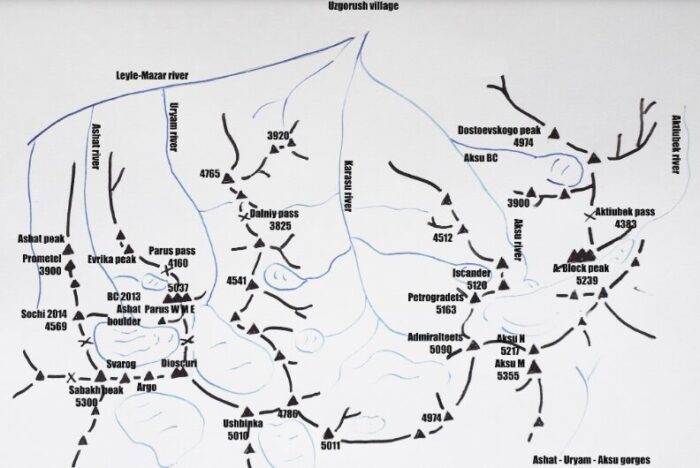

You can find out more about a 2013 expedition to the region led by Piolet d’Or winner Yuri Koshelenko here.

Map of the Ashat, Uryam, Kara-su, and Ak-su (sightly better known) Valleys. Map: Yuri Koshelenko for the American Alpine Journal

Lukashenko won the Steel Angel prize last year (the Russian version of the Piolet d’Or for women), and Kozlova and Serupova were finalists. For the 2024 expedition, the team received a Grit & Rock Expedition grant, promoting women climbers attempting new routes and exploratory expeditions.

“When applying for this grant, you need to have a preliminary route lined up, so yeah, our goal of climbing Argo, one of the points of the Ashat Wall, was pretty clear-cut,” Lukashenko said.

The climbers faced harsh weather conditions on the face. Photo: Expedition team

Getting there

But before climbing Argo Peak, you have to get there.

“The logistics were an adventure,” Lukashenko admitted. The trip involved flying to Osh – “a vibrant city teeming with people and cows, with a bustling marketplace that never stops,” then a long day’s driving to Ozgurush village, the start of their trek. Here, they loaded 200kg of gear and supplies onto the backs of donkeys and horses.

The views from base camp. Photo: Olga Lukashenko

“We set up our base camp about two or three hours from the Ashat Wall, conveniently close to a good water source,” she said. “For our ABC, we found a spot just 40 minutes away…the perfect staging ground for climbing Argo.”

The new route on West Parus Peak. Photo: Olga Lukashenko

Their main goal was the north face of Argo Peak (4,750m). They acclimatized by climbing Western Parus Peak (4,850m) via a new route on the Southwest Face (ED-, 28 pitches, 1,460m long, 1,150m elevation gain, 6c, M3, A2).

“We completed this route, primarily through free climbing, by following a massive corner system in the center of the face over 2.5 days,” Lukashenko said. “We bivouacked once midway up the wall and once near the summit. The slabs in the first part of the climb mainly involved friction climbing. The main difficulty was definitely the very strong wind and wet cracks.”

On a wet wall. Photo: Olga Lukashenko

Then they climbed Argo by a hard new route, notching the first all-female ascent of the mountain.

Their route on Argo. Photo: Russian Alpine Federation

Route details

The team graded the new route on Argo as ED, 29 pitches, 1,250m long, 950m elevation gain, 7b, M5, А3. Lukashenko described the climb as follows:

The first 500m mainly consists of mixed climbing. We started the route along an ice gully, which had completely melted by the fifth day when we were rappelling down. The ice conditions were questionable due to the warm temperatures, so we opted for mixed climbing, placing protection points in the rock and avoiding ice wherever possible. The second half of the wall is significantly steeper. The climbing was engaging, with difficulties up to 7b, though the frequently wet cracks added extra challenges.

Photo: Olga Lukashenko

The main difficulties included the wet, ice-filled cracks, loose rock, rockfall hazards, and unpredictable weather — regular thunderstorms, hail, and snow. Additionally, there were a few sections of demanding aid climbing at A3+, involving vertical, disconnected large blocks. Pulling out a protection point in these sections could potentially cause multiple points to fail and damage the rope.

As Mark Twain once said, “It doesn’t have to be fun to be fun.” This certainly holds true.

The new route on the north face of Argo Peak from a different perspective. Photo: Russian Alpine Federation

Lukashenko says that the three women made all their decisions collectively.

“We did have some lively disagreements, like whether to rappel down on the first day or ambitiously aim for the summit first, but otherwise, all was agreed without any violence or bloodshed,” she said.

Photo: Olga Lukashenko

The team had a rough division of roles: Lukashenko tackled the mixed climbing, Darya Serupova handled the rock climbing, and Anastasia Kozlova focused on the aid climbing.

“But it wasn’t set in stone—things changed and got shuffled around as we went along,” Lukashenko said.

“[The Sabakh area and the Ashat Wall] are fantastic places with immense potential for new routes,” the women concluded.