At 63, Borge Ousland is still doing long, hard polar trips. These days, it’s usually in the company of Vincent Colliard, 39, as they work their way through crossing the world’s 20 largest ice caps for their Ice Legacy Project.

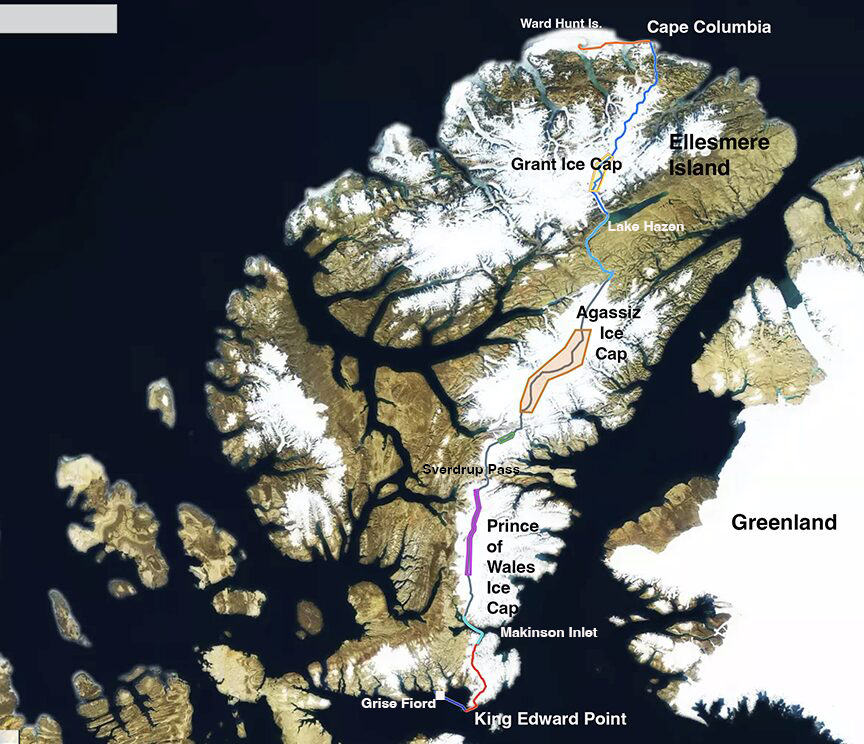

In 2025, they completed the longest of their joint ice cap crossings, a 1,100km journey from north to south across Ellesmere Island in the Canadian High Arctic, the tenth-largest island in the world. It took them 49 days, and they ticked off four ice caps in the process — the Grant, the Agassiz, the Prince of Wales, and one unnamed ice cap at the southern end of the island.

Ousland has been doing first-class endeavors in the polar regions since 1990, when he and Erling Kagge became the first to ski unsupported to the North Pole. In the 35 years since then, a handful of others have made their mark on modern polar expeditions. No one, however, has done as many important firsts as Ousland — crossing Antarctica, skiing solo across the Arctic Ocean, going to the North Pole in the dark season — twice. In some ways, he’s the polar version of Reinhold Messner.

Colliard, who grew up surfing and boxing in southern France, began as a protegé. He sought out Ousland and joined him to cross the Northwest Passage by trimaran. They did their first ice cap crossing together in 2012.

Antarctic speed record

Since then, Colliard and Ousland have skied across 13 ice caps, and Colliard has also established himself as a fine traveler in his own right. In 2024, he broke Christian Eide’s excellent 2013 Antarctic speed record from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole. Colliard averaged about 50km a day for 1,000km.

The route. Image: Ousland/Colliard

Polar bear intro

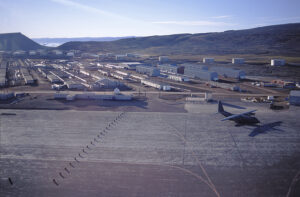

They began their Ellesmere Island expedition on April 27 from Ward Hunt Island, a small satellite just off the coast of northern Ellesmere. For Ousland, it was a homecoming: Ward Hunt has been the starting point for most modern North Pole expeditions, including his own in 1990. But now, his direction was south rather than north.

First, they started by skiing east for four days to Cape Columbia, at 83˚06’33”, the northernmost point of Canada. To add an extra element of interest, they’d decided that rather than just cross the ice caps, they’d also try the first unsupported north-south crossing of the island. Two other parties had covered that distance, in 1990 and 1992, but both had had multiple resupplies.

A polar bear approaches out of the whiteness. Polar bears do not blend into the snow, but are greyish in overcast and yellowish in sunlight. Photo: Ousland/Colliard

By late April, the worst of the winter is over. It’s still cold, but the sun’s growing strength makes windless days pleasant. Just east of Ward Hunt, they ran into one of their two close calls on the expedition — a brush with a young polar bear, which approached them briskly.

Ousland, who had dealt with too-curious bears several times before, chased it off with an aerial flare. (These flares, typically part of marine emergency signal kits, are very effective when fired at a polar bear. Unfortunately, they can’t be used as mid-range deterrents on other species of bears further south, because the burning magnesium would start forest fires.)

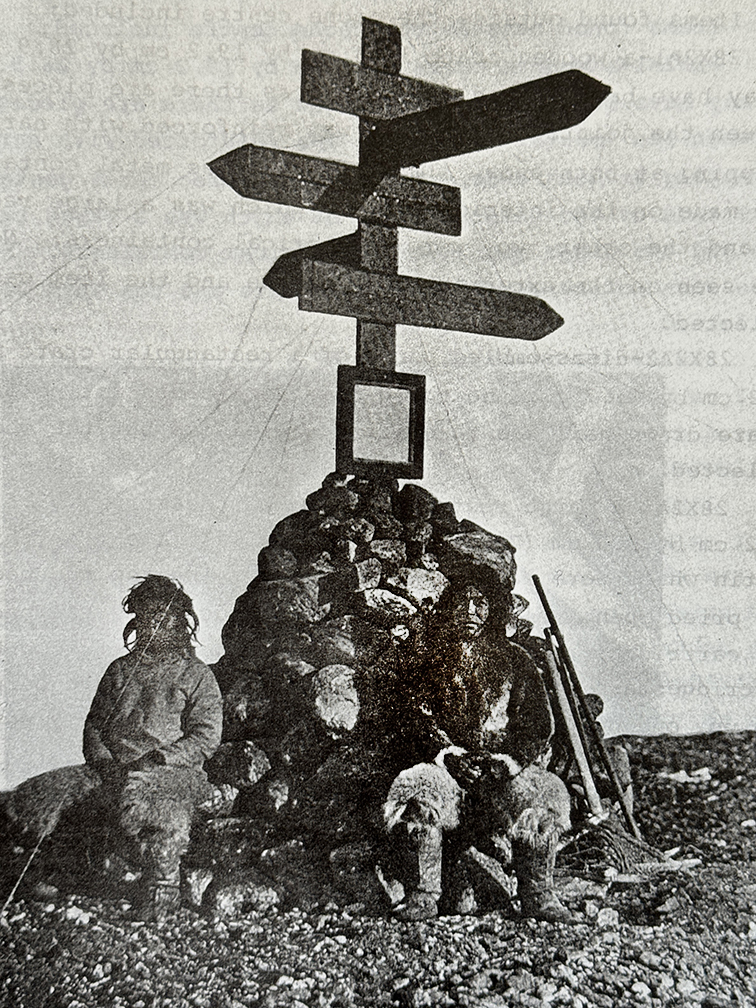

At Cape Columbia, they thrilled to the sight of explorer Robert Peary’s signpost from 1906. Though the signpost had tumbled down, the cairn was still in place, and the arms stuck visibly out of the snow.

The Peary signpost at Cape Columbia, 1906. Photo: Robert Peary

Vincent Colliard beside the signpost. A weathered wooden ski, stuck in the snow beside the cairn, is likely a Canadian military ski from the 1950s. Photo: Ousland/Colliard

First ice cap

From Cape Columbia, they doubled back slightly and went south down Markham Fiord and up a glacier onto the Grant Ice Cap. Ellesmere Island snow tends to be fairly good, and after dealing with a little soft snow, they climbed high enough, over 2,000m, that firmer snow allowed steady progress. They exited the ice cap by the Henrietta Nesmith Glacier, at the southwest end of Lake Hazen, the world’s largest lake above 80˚ north.

A few days’ travel through low, braided river valleys led to a glacial ramp up to their second and largest Ellesmere ice cap, the Agassiz. They followed it to an exit point above another channel called Sverdrup Pass, named after one of Ousland’s famous countrymen, Otto Sverdrup, who explored many parts of Ellesmere Island between 1898 and 1902.

Sverdrup Pass was a notoriously difficult route during the Age of Exploration. Until recently, a glacier blocked the narrow canyon, forcing detours over hills swept bare of snow by strong west winds. Ousland and Colliard had it easier — just one short rappel into the canyon. But they almost didn’t get to that rappel. As they were descending off the ice cap, Colliard fell into a crevasse. His sleds followed him in and lodged above him while he was on a ledge.

Colliard in a crevasse. Photos: Ousland/Colliard. Composite: ExplorersWeb

A little complacent

They admit that they’d become a little complacent after 26 uneventful days. They’d rarely roped up until then. But after Ousland extracted him from the icy tomb, the shaken travelers camped to recover — and were much more cautious thereafter.

“The snow bridges were very thin, barely 20cm,” Ousland told ExplorersWeb. “Alaskan glaciers moved faster but had more snow. You felt more secure on them.”

From Sverdrup Pass, they quickly ascended onto their next ice cap via one of the benign glacier tongues that slide down from the south. Spring was well underway by then, even on the high ice caps. When they reached Makinson Inlet and skied over to Bentham Fiord to access their last ice cap, the warm snow globbed on their climbing skins. For a while, it was like skiing in high heels.

They decided to descend the ice cap onto the sea ice of Jones Sound via the Jakeman Glacier. A researcher had died in a crevasse on this glacier a few years ago, but the skiers had no incidents. The advantage of choosing the Jakeman was that it ended in the frozen ocean, so they did not have to portage their sleds and gear over what was now, in June, snowless land.

King Edward Point marked the southernmost corner of Ellesmere Island and the successful completion of the expedition. It is also the edge of the North Water, the Arctic’s largest polynya. From here, they had just a few more days to Grise Fiord. Photo: Ousland/Colliard

Completing the traverse

They made a quick detour to the east to touch King Edward Point, the southernmost tip of Ellesmere, completing their north-to-south traverse. Then they reversed course and hurried over the sea ice for a few days to the little Inuit hamlet of Grise Fiord, the northernmost community in Canada and the end of their 49-day, 1,100km crossing.

Ousland and Colliard celebrate their arrival at Grise Fiord. Nowadays, some young Inuit snowboard those couloirs on the background mountain. Photo: Ousland/Colliard

Except for the brief lapse at the crevasse, the expedition was noteworthy for its consistent mileage, quiet competence, and lack of drama — exactly how an Arctic expedition should be undertaken.

Vincent Colliard and Borge Ousland at the Banff Mountain Film Festival last month. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko