By the autumn of 1995, Kangchenjunga — the world’s third-highest peak — had seen both remarkable achievements and serious tragedies. Its unpredictable weather and steep faces made it particularly treacherous. This season would be no different.

Ascents before 1995

The first successful ascent of 8,586m Kangchenjunga came in 1955, when a British team reached the summit. From then until the start of autumn 1995, 122 climbers had summited the mountain. Of those, 52 did so without supplemental oxygen.

But the mountain’s dangers were evident. By February 1995, 33 people had died on its slopes. Notable losses included Polish climber Wanda Rutkiewicz, who disappeared in 1992 during a solo attempt. In the autumn of 1994, an avalanche killed Russian climbers Ekaterina Ivanova and Sergey Jvirbiva at 6,700m. Just two weeks later, on October 23, Yordanka Ivanova Dimitrova of Bulgaria perished in another avalanche at 8,300m.

Wanda Rutkiewicz. Photo: Facebook

Spring and summer, 1995

In the spring of 1995, an Italian-Czech expedition led by Simone Moro targeted the Southwest Face without bottled oxygen. They pushed hard but abandoned their attempt at 8,000m in deep snow that made progress nearly impossible. This effort was part of Moro’s broader “Kangch Crossing Challenge,” which involved Kangchenjunga and Yalung Kang that season.

By autumn, the climbing community was reeling from a major disaster elsewhere. In the summer of 1995, K2 claimed several lives in a series of storms and accidents. Climbers heading to Kangchenjunga that autumn carried the weight of those events.

Four of the five points of the Kangchenjunga massif, with the main summit on the right. Photo: Peter Hamor

Six teams

That autumn, six expeditions converged on Kangchenjunga. Most focused on the Southwest Face route, which led to the West Col and then the Northwest Ridge, a path known for its technical demands.

The Italian Kangchenjunga Expedition, led by Sergio Martini, planned to use bottled oxygen on their ascent via the Southwest Face route. Martini, an experienced climber with ten 8,000m peaks already completed, aimed to add Kangchenjunga to his list.

A U.S.-Spanish team, led by Magda King Nos Loppe, also targeted the Southwest Face. They used oxygen for sleeping but abandoned their climb at 8,100m, citing exhaustion.

The Swiss-French team, led by Erhard Loretan, followed the same route. Loretan, on the cusp of completing all 14 of the world’s 8,000m peaks, was climbing with partner Jean Troillet and others.

A French party under Michel Pelle attempted the same route with oxygen but stopped at 8,200m due to a lack of fixed ropes.

Benoit Chamoux, Pierre Royer, and Riku Sherpa climbed on the Southwest Face without bottled oxygen. Chamoux, who had summited 12 of the 8,000’ers (plus a subsidiary peak on Shisha Pangma that he counted as his 13th), was filming a documentary with Royer.

Finally, a Japanese team led by Hirofumi Konishi tried the Southwest Face without oxygen but turned back at 8,400m due to fatigue and route difficulties.

These teams shared camps and routes, creating a collaborative yet competitive atmosphere at Base Camp.

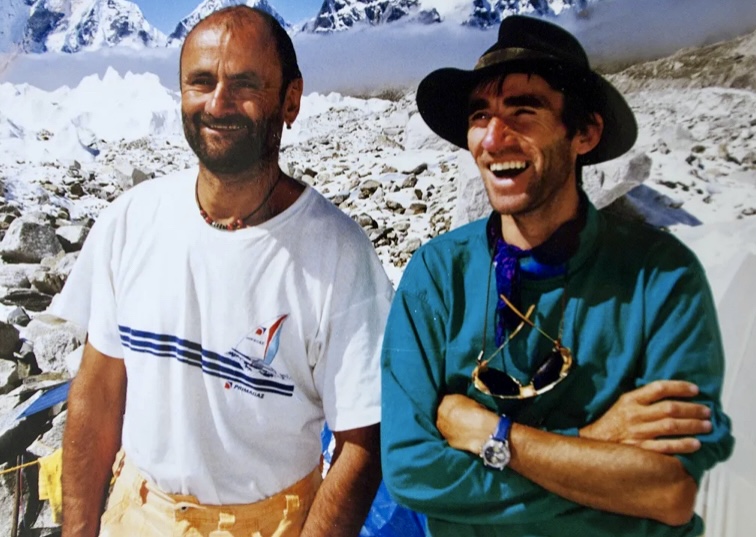

Jean Troillet, left, and Erhard Loretan at Kangchenjunga. Photo: Memorial Loretan

Summit push begins

On October 3, activity ramped up. Chamoux’s team moved from Base Camp directly to Camp 3, then established their highest camp on October 4. The next day would prove pivotal.

Eight climbers from three teams — the Swiss, French (Chamoux’s group), and Italian teams — set out from camps at around 7,800m on the Great Shelf, a vast plateau on the Southwest Face. No one carried bottled oxygen for the ascent. The group included Loretan, Chamoux, Martini, Troillet, Royer, and three Sherpas hired by Chamoux to assist with filming.

Loretan and Troillet left their bivouac at 2 am, while Martini, Chamoux, Royer, and the Sherpas departed from nearby at the same time. They climbed together until about 9:30 am, reaching around 8,250m at the intersection of couloirs leading to the ridge.

Benoit Chamoux at K2 in 1986. Photo: Benoit Chamoux

A fatal slip

Tragedy struck suddenly, according to Miss Hawley’s report for the American Alpine Journal. One of Chamoux’s Sherpas, Riku (a 33-year-old from Sankhuwasabha), lost his balance while sitting with his rucksack on. He fell to his death, tumbling down the slope. The other two Sherpas descended immediately, leaving Chamoux and Royer without support. Riku’s body lay at 7,600m, passed by climbers daily, but it was too difficult to move.

The Swiss and Italian climbers felt the French party was moving too slowly, so Loretan, Troillet, and Martini pressed ahead. However, Martini soon doubted the route, wary of a rock pillar and strong winds. He waited half an hour for the Swiss to return but, with no sign of them, turned back at 8,200m below the West Col at 8,350m. He attempted a couloir alone but found the snow-on-rock conditions too dangerous in the bitter cold and descended.

The Southwest Face of Kangchenjunga. Photo: Philippe Gatta

Loretan and Troillet forged on, reaching the West Col at 11 am. They found an “easy way” along the rock-and-snow ridge connecting the main summit to Yalung Kang. Despite extreme cold and swirling snow from high winds, they summited at 2:35 pm. The wind eased at the top, allowing a brief stay before they started down at 3 pm. They reached their camp at 7,300m by 5:30 pm. Loretan stayed overnight with teammates, while Troillet continued to Base Camp, arriving at midnight.

With this ascent, according to the valid list of the time, Loretan became the third person — after Reinhold Messner and Jerzy Kukuczka — to summit all 14 8,000ers. At 36, he was also the youngest. Back in Kathmandu, he downplayed the feat: “It’s something done.” He preferred to eye future projects, like Makalu’s unclimbed West Face.

The disappearance of Chamoux and Royer

As Loretan and Troillet descended the ridge around 4 pm, they met Chamoux and Royer still ascending, now alone after the Sherpas’ departure. Royer, carrying his cameras, radioed at 4:30 pm that he was turning back due to exhaustion. An hour later, Chamoux radioed that he was also too tired to continue. He claimed to be 40m below the summit but couldn’t find the way down the ridge. He had lost sight of Royer, who had given him the radio. Chamoux bivouacked on the ridge, just above the West Col.

At 8 am on October 6, Chamoux radioed Troillet for descent guidance. Climbers saw him reach the col, but Chamoux then vanished on the north side. Neither he nor Royer was seen again.

Erhard Loretan. Photo: Cordada

A search began immediately. On October 6, Michel Pelle and a client reached Camp 4 but saw nothing. The next day, two of Pelle’s Sherpas fixed ropes to 8,200m. Chamoux’s surviving Sherpas refused to search, upset that no aid was given to Riku Sherpa after his fall.

Aerial searches by helicopter and plane yielded nothing. Climbers on nearby Gimmigela used telescopes to scan Kangchenjunga’s North Face and summit area, but spotted no trace of either man.

Martini’s second attempt and discoveries

Martini, recovering from his first summit bid, descended to Base Camp. On October 12, he and teammate Abele Blanc headed up again, reaching Camp 2 at 7,200m. On October 13, they made Camp 3. On October 14, they summited via Loretan’s route in six hours. Though planning an oxygen-free climb, they used another team’s oxygen to ensure they could search for Chamoux and Royer.

Near the West Col, they found some clues: footprints in wind-hardened snow, a bivouac spot, and items including two ice axes (one long, one short), Royer’s small backpack with two cameras, two harnesses draped on a rock, and a radio propped higher up. Martini brought the backpack to Base Camp, and his Aosta teammates later took it to Europe.

Yet they found no bodies. Loretan speculated that Chamoux and Royer fell down the North Face. Martini thought they might have died among the rocks near the col, hidden from view, perhaps freezing after resting without the strength to rise and continue. The area had no crevasses to swallow them.

Sergio Martini on Makalu in 1985. Photo: Archive Almo Giambisi

Competition and risks

At Base Camp, teams discussed whether competition among top climbers (Loretan, Chamoux, and Martini) had added unnecessary risk. One French climber called it a “fatal challenge” for Chamoux, racing Loretan for the 14 peaks title.

“The Swiss were much faster. Loretan is the best,” he said.

An American climber was direct: “The French were not well acclimatized. They tried to keep up with the Swiss, and they killed themselves.”

Reports noted Chamoux’s team had vomited at Camp 3 on September 17 and descended abruptly, not returning to high altitude until the summit push. Troillet remarked that the Chamonix climbers were highly competitive.

Chamoux’s group had pushed from Base Camp to Camp 3 on October 3, then to their high camp on October 4 before the ill-fated attempt. The Swiss, recovering from minor ailments in early September, had acclimatized with a foray to 7,400m on October 15, sleeping at 7,300m before bad weather hit.

The season ended with mixed emotions. The Japanese and U.S.-Spanish teams abandoned high up. Pelle’s French team reached 8,200m but no further. Loretan’s historic completion and Martini’s perseverance were notable, but three people died: Riku Sherpa, Benoit Chamoux, and Pierre Royer. The season demonstrated the fine line between ambition and survival in the Death Zone.

Kangchenjunga from Gangtok, Sikkim. Photo: Johannes Bahrdt