In May of 1622, the English East India Company ship Tryall became the first English ship to sight the coast of Australia. Shortly after, it became the first ship to sink off the coast of Australia.

The story of the Australia’s oldest shipwreck covers 400 years, from a suspicious sinking to a pair of castaway journeys, a court case, a geographical mystery, and a modern scandal involving the misuse of explosives at an archaeological site.

A diver investigates the wreck of what archaeologists are pretty sure is the ‘Tryall’. Photo: Western Australian Museum

The maiden launch of the Tryall

The Tryall (also spelled Triall, Tryal and Trial) set sail from Plymouth on Sept. 4, 1621. She was a British East Indiaman, a mercantile vessel built to travel between England and the Global Southeast, then called the East Indies.

Owned by the British East India Company, her generous hold was filled with textiles, silver, and supplies bound for Batavia — present-day Jakarta, Indonesia. This was to be her maiden voyage, and an inspection by EIC officials at the docks found her in good condition.

Her Captain was John Brookes. The other key man aboard was Thomas Bright, the EIC’s representative, or “factor” for the voyage. One hundred and forty-three seamen rounded out the crew, and after a brief pay dispute, they sailed for the Cape of Good Hope.

This stage of the journey went fine. They arrived at the tip of Africa, took on fresh supplies, and set off for Batavia on March 19. By a new, dangerous route.

This ship is a reconstruction of a Dutch East Indiaman, about the same size as the ‘Tryall.’ Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Another way to India

At the turn of the 17th century, the standard route from Cape Town to Batavia came from 15th-century Portuguese explorers, who used the seasonal monsoon winds to cross the Indian Ocean. It took about 12 months.

The Dutch decided that if they were going to steal the spice trade from Portugal, they had to do better than that. So Hendrik Brouwer took an alternative way in 1611. It became known as the Brouwer route.

The new route cut travel time in half by ducking down into the Roaring Forties and using their strong westerly winds to cross the Indian Ocean. The key was the timing of that northeast turn. Too early, and you’d end up in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Too late, and you’d crash into Australia.

They didn’t know that yet, though. A few Dutch explorers had sighted some islands off the Australian mainland, but no one suspected a whole continent might be in the way.

The problem with that all-important turn is that, at the time, there was no good way to determine longitude at sea. Ships would have to make the turn using dead reckoning, which is a fancy nautical term for “guessing.” In 1620, the British EIC decided to copy the Dutch and sent Captain Humphrey Fitzherbert to test the route.

He had a great time and gave it a thumbs-up, so they gave Captain Brookes a copy of Fitzherbert’s journal and told him to do the same thing.

This map of the Brouwer route shows the Roaring Forties, a band of strong westerly winds between 40 and 50 degrees latitude. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The wreck of the Tryall

Brookes was nervous about the new route. In Cape Town, he met Captain Bickell, another EIC Captain. He asked Bickell if he could borrow one of his experienced mates to help navigate, and Bickell gave him permission. But Bickell’s ship, the Charles, was on its way home, and none of her mates were willing to delay their return to help.

Brookes had to sail on, with only the 1620 journal and imperfect charts as a guide. The Tryall descended to 39 degrees latitude, and the Roaring Forties drove them east.

On May 1, they spotted land. They had just become the first Englishmen to see Australia. Brookes and Bright both describe a great island, because from their perspective, a pair of points made the coast look like an island. Brookes turned north for the run up to Java, but was kept in place by contrary winds. Finally, on May 24, he was able to head north.

The next day, late in the evening, in calm seas, the Tryall struck rocks. Brookes ran up on deck, giving orders to tack west, hoping to dislodge her. A strong, brisk wind began to blow as water flooded into the ship, the sharp rocks tearing her timbers apart. It was too late, Brookes realized, to save her. He “made all ye meanes I could to save my life and as manie of my compa[ny] as I could.”

He launched the ship’s two boats. Ten, including Brookes, climbed into the skiff, while 36, including Thomas Bright, piled into the pinnace. Less than six hours after striking rocks, the fore-part of the Tryall broke up. Ninety-seven died.

Paintings tend to show ships driven onto rocks by a storm. Running right into them in calm weather is less dramatic. Photo: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Brookes’ story

Brookes’ skiff launched first. With him were nine sailors and a cabin boy, who would definitely be eaten first if it came to cannibalism. They had several cases of spirits and kegs of water, but only four pounds of bread. They landed briefly on a low island, now known to be Barrow Island, then set off again.

On July 5, they arrived in Batavia, and Brookes sent his report to his EIC superiors. Fitzherbert must have overlooked the land they sighted on May 1, he explained. “He went 10 leagues to ye Southwardes of this iland,” Brookes asserted, before making the northeast by east turn. Brookes said that after sighting this land, he also made a northeast by east turn.

That Fitzherbert had missed the rocks was pure chance; his ships had sailed right past destruction without realizing it. The wreck of the Tryall could have happened to anyone. The EIC agreed. So they gave him another ship, the Little Rose, to explore the area around Sumatra. When he got back, they put him in charge of the Moone.

This Dutch map from 1627 records the position of Trial Rocks as given by Brookes. Photo: National Library of Australia

The wreck of the Moone

Brookes was taking the Moone back to England with a few other EIC vessels. But the Moone was wrecked off the coast of Dover, and with her went £55,000 worth of cargo, about $14,000,000 today. John Brookes and the ship’s master, Churchman, began accusing each other of misconduct, and the EIC threw them into prison.

In court, Brookes made multiple lengthy speeches protesting his innocence. He also stressed, once again, that the Tryall wreck was not his fault. Regarding the Moone, Brookes blamed the ship’s poor condition, calling it worm-infested and half rotten.

Witnesses, however, testified that he had discussed deliberately sinking the ship back in Cape Town. He was accused of deliberately sinking the ship in an elaborate heist of the valuable cargo. In fact, when the wreck site was examined, most of the cargo was missing. Multiple eyewitnesses also claimed Brookes had used the confusion of the sinking to break open and pilfer a chest of jewels.

The court case dragged on for years before finally being settled out of court. While he was never convicted, Brookes had lost all of his money and reputation. But with all the back and forth about stolen diamonds and the Moone, his claims about the Tryall went unchallenged. There was one man, however, willing to challenge John Brookes: Thomas Bright.

Churchman and Brookes spent several years imprisoned in Dover Castle. It was being used as a prison, though the Duke of Buckingham was also there, making alterations to the great tower. The EIC appealed to him to bring the trial to an end, but he was busy being assassinated at the time. Interesting guy. Photo: Historic England Archive

Bright’s story

In a series of letters, Thomas Bright gave his side of the story. The fact that they’d hit the rocks at all, he claimed, was due to Brookes not keeping a proper lookout. Once the ship was struck, he described Brookes rushing to provision his own boat. He even personally betrayed Bright (“like a Judasse”) by promising to take him, then launching the skiff while Bright wasn’t looking. The skiff then made straight for Java without waiting to see what became of everyone else.

The pinnace, or longboat, launched an hour and a half after the skiff, with 36 men aboard. They had a couple of pounds of bread, some bottles of wine, and a single barrel of water. The sea was too rough to do anything but keep in sight of the crumpling ship, weathering the waves, until morning. In daylight, they made for a nearby island.

They spent a week on a low, uninhabited island, now known as North West Island. There, they repaired the pinnace and tried to stock up on provisions for the journey ahead. Bright kept himself busy drawing maps and charts of the surrounding area, becoming the first Englishman to map parts of Australia.

The pinnace successfully reached Java in late July. Bright was furious at Brookes and the lies he had been spreading. He wrote detailed letters and drew maps and charts laying out Brookes’ deception — but they went unheeded, and then were lost.

The islands where Bright landed are now better known for being a British nuclear test site in the 1950s. Photo: Montebello Islands Conservation and Marine Park

The search for the Trial Rocks

Both the British and Dutch East India Companies (referred to as EIC and VOC, respectively) were concerned that their trade route had secret, deadly rocks somewhere along it. Brookes advised the company to avoid going too far south, theoretically avoiding the Trial Rocks but also reducing speed.

In 1636, the VOC sent a pair of ships under Gerrit Tomaszoon Pool. His instructions included “trying in passing to touch at the Trials,” to gather information about their exact location. But he didn’t find them.

As the years went on, sailors and mapmakers alike were confused as to where the rocks were and whether they existed. By 1705, the Commodore of the Dutch Ships reportedly didn’t believe they were real, at least not in the position Brookes had indicated.

By the late 18th century, even the story’s origins were hazy. A 1780 directory of the East Indies claimed that the Trial Rocks were “discovered by a Dutch ship in 1719.”

In 1803, English Captain Matthew Flinders took many soundings in the area on his way back from Timor. He spent weeks searching for the rocks despite the fact that illness was rampant aboard ship.

Finally, he concluded that “the Trial Rocks do not lie in the space comprehended between the latitudes 20° 15′ and 21° South, and the longitudes 103° 25′ and 106° 30′ East.” Thus concluded, they set sail, hoping to get better food for the sick, as “the diarrhoea on board was gaining ground.”

His hard-won findings convinced the British Admiralty, which declared the Trial Rocks nonexistent.

An 1820 map shows the Trial Rocks in what we now know is an incorrect position. Photo: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

The (re)finding of the Trial Rocks

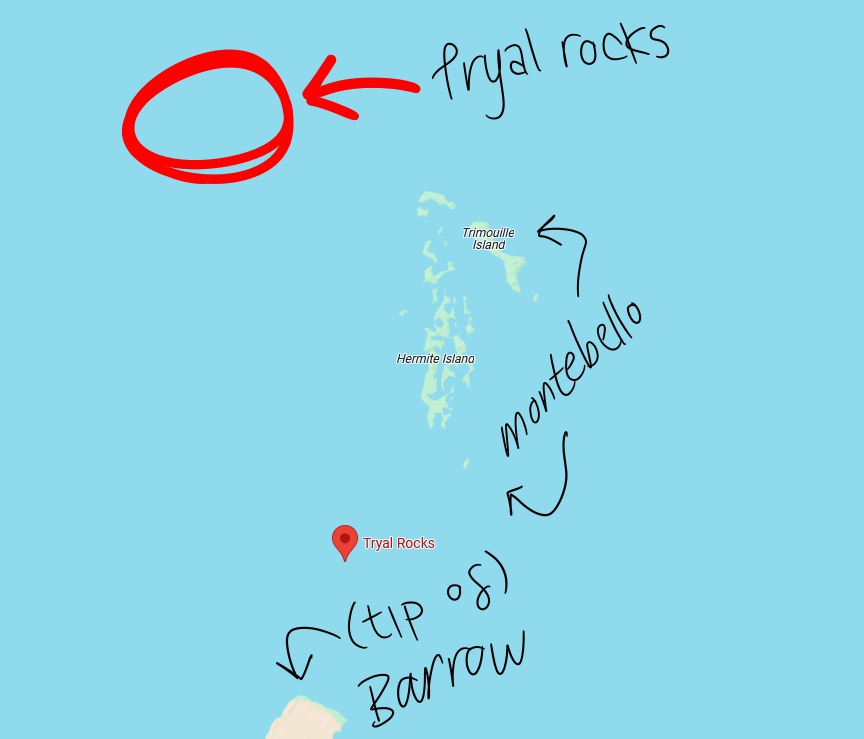

Today, we know that the Trial Rocks lie just off the Montebello Island group, off the coast of Western Australia. The definitive identification of the Trial Rocks came in fits and starts, being repeatedly made and then forgotten.

In 1818, the Greyhound had a run-in with the rocks, managing to avoid being sunk through luck and good spotting. As she was captained by one Thomas Richie, the rocks became known as Richie’s Reef. Two years later, another brig passed through the area and had a look-see.

Aboard was Lt. Phillip Parker King, who recorded his belief that the Trial Rocks were, in fact, located around the area of Barrow Island and the Montebello Islands. The next Admiralty chart placed Richie’s Reef to the northwest of Montebello, and a second, separate set of Trial Rocks between Montebello and Barrow. They were only wrong by 42 kilometers, which was at least an improvement.

Enter Australian historian Ida Lee. She uncovered the letters by Bright and Brookes and consulted Rupert Gould. Before he became really into the Loch Ness monster, Gould was a member of the Hydrographer’s Department at the Admiralty, a respected expert on cartography and naval history.

He replied confidently: Richie’s Reef was the Trial Rocks, and Captain Brookes had intentionally deceived everyone about where the rocks lay.

Left, the site of the wreck as described by Bright. Right, Montebello island chain. Drawn by Rupert Gould. Photo: UK Hydrographic Office via WA Museum

Captain Brookes’ great deception

Have you ever really messed up at work? I mean really, really messed up? Imagine if you messed up so bad that nearly a hundred people had died and a huge ship full of valuable trade goods had been lost. Would you lie about it? Be honest.

The truth was that the rocks hadn’t been anywhere along the Brouwer route. Brookes had gone too far east, overshooting his turn so badly that they’d sailed right into the coast of Australia. Realizing he went too far, Brookes then headed directly north, instead of northeast, running into the Trial Rocks.

When it came time to write his account, he claimed to have turned earlier and been headed northeast. He told the same lie about the skiff journey, claiming to have traveled northeast instead of east. If he had actually traveled northeast from the Trial Rocks, he would’ve missed Java entirely.

Brookes had lied about where the rocks were to disguise his mistake, claiming they were hundreds of kilometers west of their actual position. This was not an innocent deception. As the men who died on the Tryall could tell you, knowing where hidden rocks lay was a matter of life and death.

Bright had tried to get the real story out in his letter. But that had been lost to the depths of the archives until Ida Lee. In 1934, Lee published her article, and henceforth, the rocks were placed in the correct location. Except, apparently, on Google Maps, which inexplicably gives the pre-1934 location.

How did this happen? Photo: Google Maps/Ravings of a madman (the author)

The Tryall gets blown up

No one actually went looking for the wreck until the late 1960s. Two men from a group called the Underwater Explorers Club, John MacPherson and Eric Christiansen, got Gould’s report from the Admiralty Hydrographic Office. A few years later, Christiansen led a small party of divers to the wreck site. For our purposes, the most important member of this group was Alan Robinson.

They dove at the Trial Rocks in May 1969. On the southwestern side of the rocks, they found an old anchor, then another, and then cannons — it was a wreck site. They reported the find to the Western Australia Museum and collected a finder’s fee equivalent to about $18,500.

The WA Museum organized an expedition, but poor weather prevented them from doing much diving. In 1971, they came back with more funding, but when they dove down to the site, they found it had been vandalized — with explosives. The reef itself was damaged, along with some of the cannons and anchors, and the various smaller artifacts one would expect around the site were nowhere to be found.

The suspected culprit was Alan Robinson. A notorious figure in Australian maritime archaeology, Robinson was a treasure-hunter who frequently came into conflict with the laws around salvage and cultural artifacts. He was acquitted of the charges regarding the Tryall site, but we’ll probably never know the truth.

Robinson died in jail while awaiting trial for attempting to murder his ex-wife, so was unable to confess about using blasting gelatin on Australia’s first shipwreck.

These coins, produced in 1711, were recovered from the wreck of the ‘Zuytdorp’, another sunken ship Robinson was accused of pilfering. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

An active archaeological site

Several more expeditions visited the damaged wreck site. Like many of the most famous Australian shipwrecks, any write-up of work on the Tryall site must mention the contributions of Dr. Jeremy Green. Green wrote the book on maritime archaeology, and by the discovery of the Tryall, had already led the investigations of the Batavia and Vergulde Draeck.

It was Green who led the 1971 dives and who gave the first tentative identification of the wreck as that of the Tryall. Because of all the missing artifacts, it’s difficult to say beyond a shadow of a doubt that the ship found on Trial Rocks is really the Tryall. In addition to the location, Green used the cannons and anchors to confirm that they were looking at the remains of an English merchant ship from the early 17th century.

Divers investigate the wreck site at Trial Rocks in 1985. Photo: WA Museum

Subsequent dives have provided further evidence that this is, in fact, the Tryall, such as the makeup of the ballast stones. The most recent expedition took place in 2021, where they confirmed that there were no other wrecks in the area. Since we know that the Tryall wrecked there, and there is only one wreck, it must be the Tryall. After centuries of doubt, we finally have certainty.

The Western Australia Museum recently completed the restoration of one of Tryall‘s cannons, which is now on display in the museum.