For some, there’s little doubt the so-called “Tully monster” is straight nightmare fuel. For others, it would probably amount to a biological curiosity, not too different from a geoduck or a sea cucumber.

But did this prehistoric wormlike creature that probably looked like a cross between a squid and a one-armed crab have a backbone? Or any bones at all?

That inquiry has hounded scientists ever since the Tully monster’s discovery 70 years ago. And now, they think they’ve finally found the answer.

University of Tokyo graduate student Tomoyuki Mikami and his team published a study April 17 on the curious 15cm beast, which lived in the Carboniferous period 300 million years ago. In it, the researchers draw the conclusion that the Tully monster was — after all — an invertebrate.

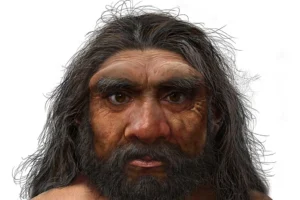

An artist’s rendering of the Tully monster. Photo: Nobu Tamura via Wiki Commons

“We believe that the mystery of it being an invertebrate or vertebrate has been solved,” Mikami said in a press release. “Based on multiple lines of evidence, the vertebrate hypothesis of the Tully monster is untenable. The most important point is that the Tully monster had segmentation in its head region that extended from its body. This characteristic is not known in any vertebrate lineage, suggesting a nonvertebrate affinity.”

The finding could cause little surprise in anyone who’s seen any of the widely available array of rubber fishing lures. It’s possible you’d be more weirded out if it turned out the finned aquatic wriggler had bones.

That’s all except for the bizarre structure at its little end — is that thing a claw or some kind of prickly mouth?

Actually, scientists still don’t know. And that’s part of the Tully monster’s curious command over the paleontological community: Its resistance to general methods of classification.

History of the Tully monster

It all started in the 1950s — in the U.S. state of Illinois, of all places. Amateur scientist Francis Tully was “enjoying his hobby fossil hunting” in an area known as Mazon Creek Lagerstätte, according to the University of Tokyo, when he unearthed the puzzling specimen.

Tully recognized right away that unlike dinosaur bones and hard-shelled creatures that most often become fossils, this petrified creature was soft-bodied. That’s because Tully discovered it in one of the few places in the world where the conditions were just right to preserve soft tissues before they could decay.

View this post on Instagram

Tully certainly had a rare find (which came to define his legacy). And it spurred excitement in the scientific community. Some suggested that it could be a missing piece in the puzzle of vertebrate evolution.

Though it appears that possibility is no longer on the table, research into the Tully monster is not over. The next steps for Mikami and his team involve deciphering what group of organisms it does belong to. It’s possible that it’s a nonvertebrate chordate (similar to a lancelet) or some variety of protostome (a diverse group of animals that includes, among other things, insects, roundworms, earthworms, and snails).

Speaking for myself, I’d just like it if the team could figure out what it was doing with that frightening, spiky extremity. You would not have caught me swimming in Carboniferous period Illinois, that’s for sure.

“There were many interesting animals that were never preserved as fossils,” Mikami said. “In this sense, research on the fossils from Mazon Creek is important because it provides paleontological evidence that cannot be obtained from other sites.”