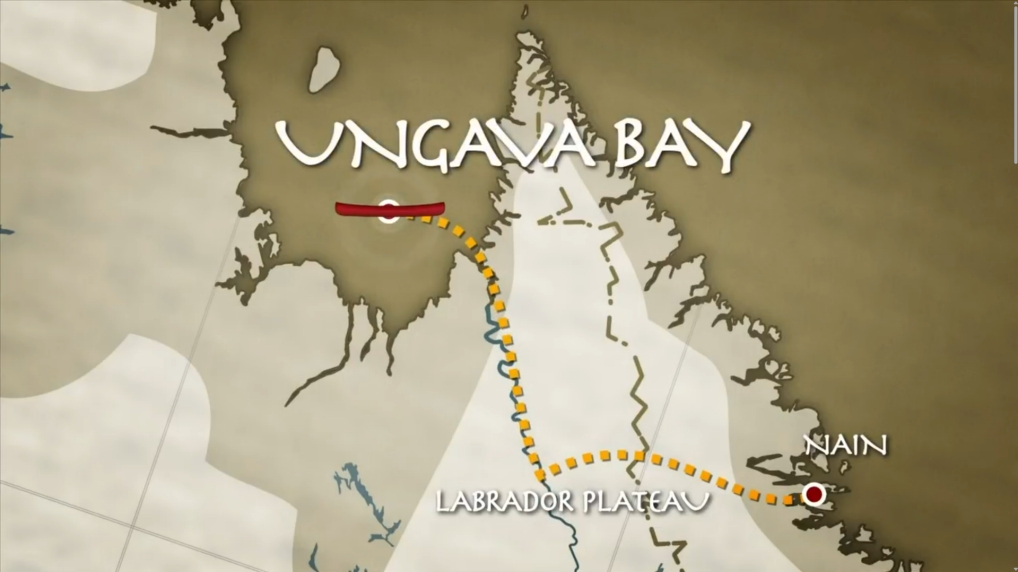

Kitturiaq chronicles a 620km canoe expedition across the Labrador plateau down the George River in Canada’s northern Quebec. Professional adventurer Frank Wolf undertook the journey with partner Todd McGowan.

A map of the planned route from Nain to Ungava Bay, by way of the Labrador Plateau. Photo: Screenshot

Wolf is bold in adventure planning and is perfectly willing to be bold in filmmaking, too. The film’s narration is delivered by a fictional mosquito who chooses to tag along as an unofficial third party member. In fact, the Inuktitut word for mosquito gives the project its title.

Meanwhile, the Kitturiaq, named Malina, shares the story of explorer Hesketh Hesketh Prichard. (Evidently, his parents felt that one “Hesketh” wasn’t enough.) Through Malina’s narration, the story of the Briton’s failed 1910 attempt to complete the route unfolds simultaneously to the main action.

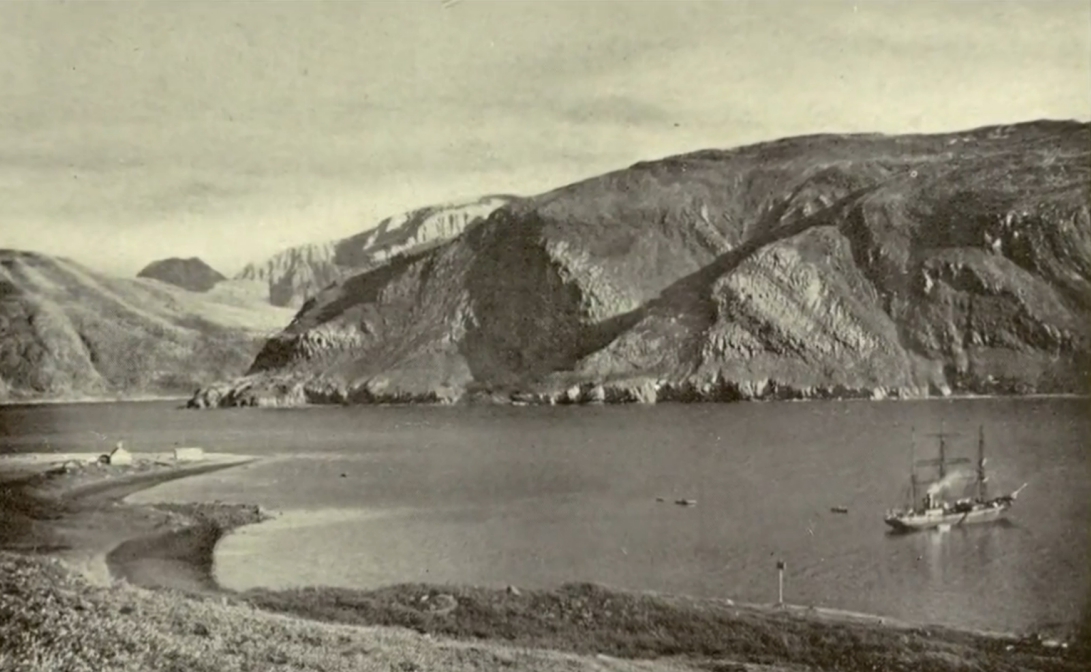

Prichard’s ship, the ‘Harmony,’ brought his expedition to Nain in 1910. A few years later, in 1918, the Harmony brought the deadly Spanish flu to northern Labrador. Photo: Screenshot

The journey begins in Nain, now the northernmost town on the Labrador coast and the administrative capital of the Inuit region of Nunatsiavut. There, Wolf interviews local community leaders about the land his upcoming journey will take him through.

A 600m climb, with canoe

The first stage takes them a little north to the giant Fraser Canyon, which they must scramble up to the Labrador plateau. Malina’s blackfly relatives are thick in the air, just as locals warned they would be.

But it’s the portage they have to make that is the real killer. With no waterway to follow, they have to unload their gear, then drag it and the canoe 600m up a crack in the cliffs called Poungassé to the top of the plateau. Sweat and blood cover them both by the time they reach camp, and McGowan suffers sunstroke. The long subarctic summer day can be blisteringly hot.

McGowan collapsed from the heat, and they had to break for him to rest. Photo: Screenshot

They’re still doing better than Prichard, who took a steeper route and ended up abandoning one of his canoes. Atop the plateau, Prichard saw no waterways — the plateau is mostly swamps and shallow ponds in this area — and abandoned his last canoe, continuing on foot. Wolf and McGowan elect to drag theirs. After a brief descent into fly-induced madness, they’re back on the water.

“People have been here, a long, long time before us,” Wolf reflects, examining a piece of wood. No trees grow on the tundra, so an Inuit hunter must have brought the discarded log on his sled, or komatik, years before. This small moment is a quiet reflection on a core theme of the film.

The paddling and portaging continue. “They’re beginning to act a little strange,” Malina notes. A headnet makes a reappearance.

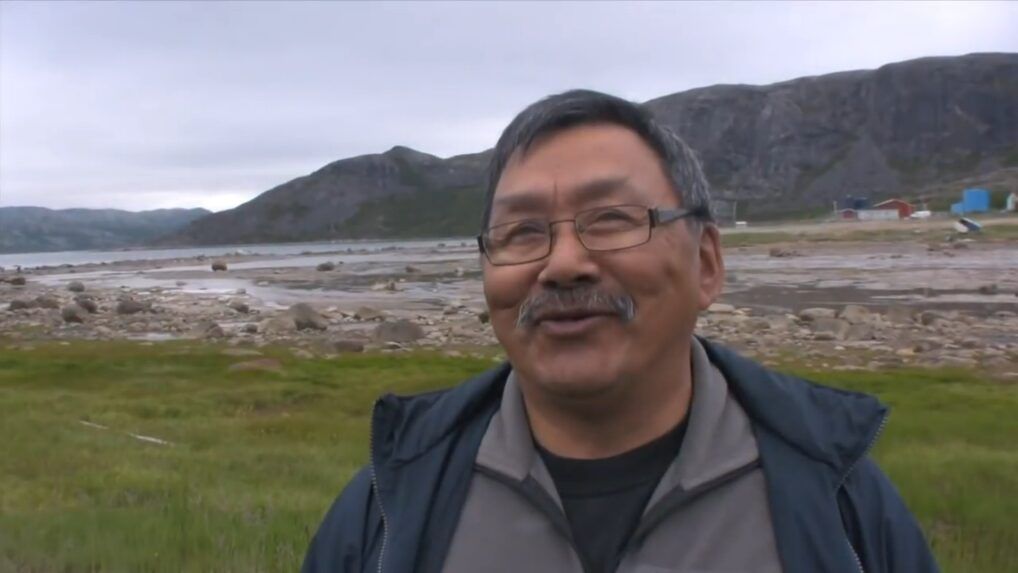

When they make it to Nunavik, they go fishing, while Nain politician Johannes Lampe reflects through a previous interview about how prohibitively expensive food is this far North. Caribou is much more cost-effective than groceries, and fishing is cheaper than buying fish. The land takes care of you, Lampe explains, when you take care of it.

Johannes Lampe was Minister of Culture, Recreation and Tourism for Nunatsiavut at the time of filming. He is currently President of Nunatsiavut. Photo: Screenshot

The George River

When Prichard and his team reached the George River, they hoped to meet the local Innu people. But these elusive people had already passed on to different hunting grounds. Without any canoes to handle the George River, Prichard had to turn back.

But Wolf and McGowan’s portage drudgery paid off, and they still have theirs. Once they reach the George River on day 17, the kilometers begin to fly by. Speaking of flies, they remain innumerable. Soon, the canoeists reach the end of the river at Ungava Bay.