When Yellowstone erupts again, as it certainly will, it won’t matter whether people live in Bozeman, Montana or Cody, Wyoming — they’ll be just as dead. But new seismological research has finally nailed down where exactly the eruption will breach the ground. If you want to die by magma instead of ash, the northeast of the park is the place to be.

Hikers need not worry. A team from the United States Geological Survey (USGS), publishing last week in Nature Geoscience also measured the percentage of rock in Yellowstone magma reservoirs that’s actually melted. They found that none of it is near levels where an eruption is imminent.

Mount Saint Helens, before and after a lateral eruption blew up half the mountainside. Photo: USGS

Yellowstone magma close to the surface

When Mount Saint Helens erupted in 1980, most of the upper part of the mountain broke off and slid down the slopes in a massive avalanche. What was left behind was a caldera. This crater-like divot in the rock isn’t fed by a narrow vent like typical volcanoes. Instead, a large magma pool sits right below a shallow surface rock layer.

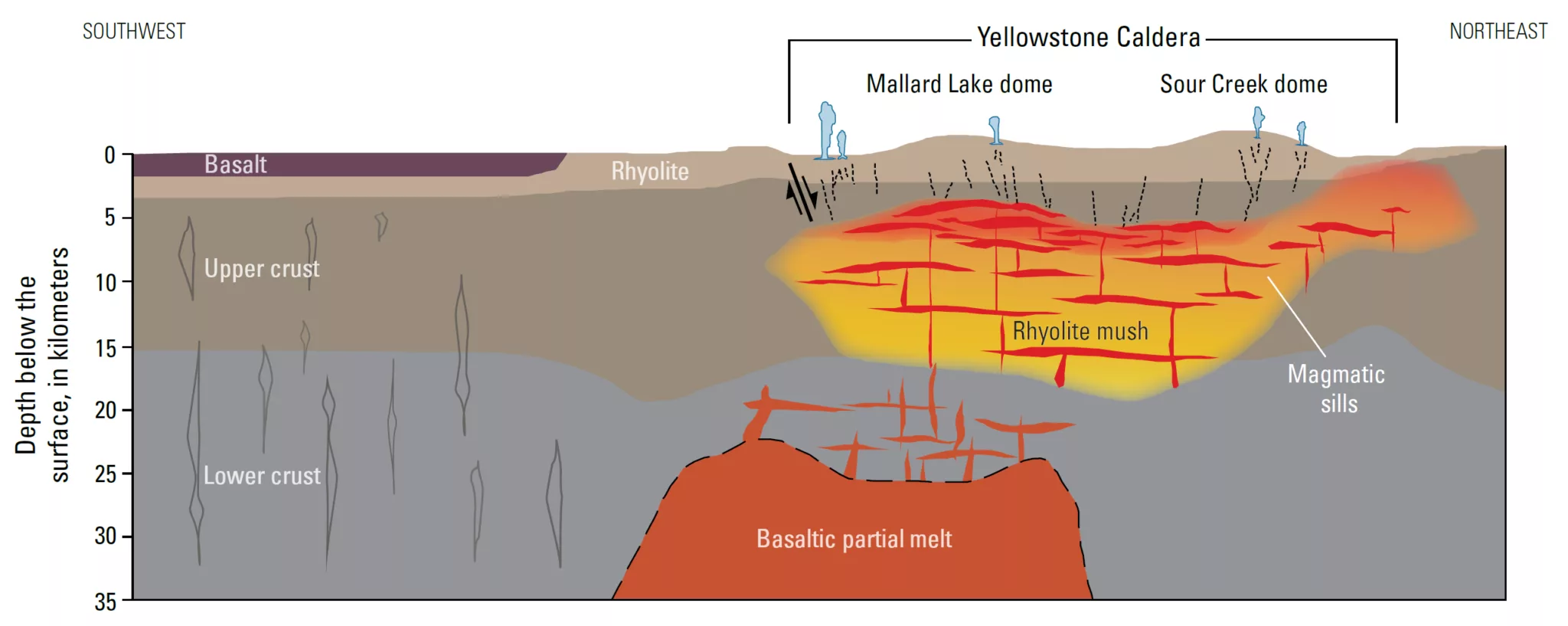

That’s what lurks beneath the surface at Yellowstone National Park. But unlike Mount Saint Helens, the Yellowstone caldera doesn’t just have one magma reservoir underneath it. It has four.

The Yellowstone caldera has a long history. It erupted at least three times before, mostly recently 70,000 years ago. Previous eruptions have left the northeast relatively untouched, but that will change when the next eruption comes.

To locate magma, the USGS team used a network of stations that measured the conductivity of material deep into the ground. This method, called magnetotellurics, relies on the fact that solid rock is very resistant to electric currents. As soon as rock starts melting, however, electric currents can flow through it. So magma appears on the magnetotellurics measurements as pockets of high subterranean conductivity.

These magma hotspots aren’t really underground pools like aquifers but rather a honeycomb mix of solid and melted rock. As long as the melt percentage stays below 40%, the different pockets in the honeycomb can’t gather enough pressure to erupt out of the ground. The largest melt fraction found in the new research is only 18%, and that won’t increase much within the next few decades.

Magnetotelluric stations like this one in Antarctica were installed all over Yellowstone. Photo: Kerry Key/Columbia University

Where the magma runs deep

A schema of the Yellowstone magma system in the northeast. Photo: Yellowstone Volcano Observatory

Although the USGS identified pockets of melted rhyolite rock under all of Yellowstone, channels of magma connect the northeast rhyolite melt pockets to deeper reservoirs of molten basalt. Magma made of rhyolite produces characteristic volcanic ash, but basalt is the real driver of eruptions because it flows more easily. That means it can circulate heat from deep within the Earth, pushing molten rhyolite to the surface.

Right now, the volume of magma under Yellowstone is larger than in any of the previous eruptions. It’s hard to know how much of that will still be there when the caldera finally blows.