Ancient Egyptian pharaohs, including the famous Hatshepsut, sent sea voyages to trade with the distant kingdom of Punt. Centuries of ancient explorers like Hannu and Nehsi voyaged to Punt, bringing back golden riches, spices, incense, ebony, ivory, and exotic animals.

Punt was a land from poems and stories, of golden mines and sweet-smelling resins, far away over the sea. Its association with the aromatics used in worship gave it the name “Land of the Gods.”

By the end of the New Kingdom era, however, it had fallen into legend. Today, the kingdom survives in Egyptian records and a handful of artifacts. We know it existed, but historians still debate where the kingdom of Punt actually was, and who lived there.

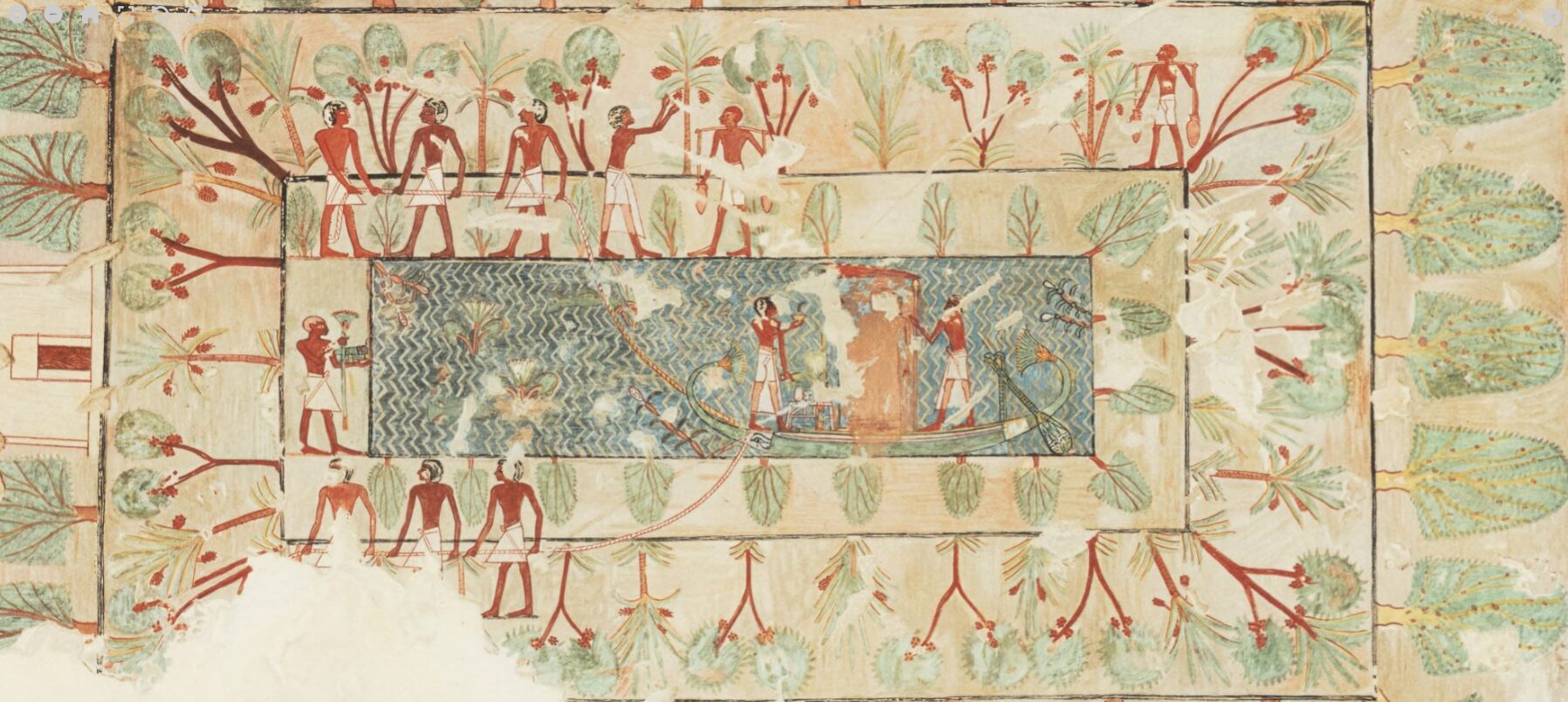

Painted on the wall of a tomb, this artwork from the 15th century BCE shows men from Punt. The men are bringing gifts, representing their main exports. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Punt in the Old Kingdom

We don’t know for certain when the Egyptians and the people of Punt, also anglicized as Pwenet, first came into contact. The first recorded expedition occurred under the 5th-dynasty pharaoh Sahure, in the 25th century BCE. Sahure invested heavily in Egypt’s navy and trade networks, sending expeditions to the Levant, Sinai, and Punt.

An important record of the Old Kingdom, the Palermo stone, records the wealth Sahure’s Punt expedition brought back to Egypt: 80,000 units of myrrh, 6,000 of electrum, and 23,000 staves, possibly of ebony. We don’t know what the units of measure were, but 80,000 anythings of myrrh is a great deal of myrrh. They also brought frankincense cuttings, which Sahure attempted, without success, to cultivate in Egypt.

For the remainder of the Old Kingdom, trade with Punt continued, though the expeditions were infrequent. The voyage would have been long and dangerous. In fact, the last Old Kingdom pharaoh, Pepi II, had to send an expedition to collect the body of the previous, failed expedition’s leader.

Under the very long reign of Pepi II, who ascended to the throne at age six and died between 62 and 94 years later, several expeditions went to Punt. His records also reference an expedition that occurred around 60 years earlier, in the reign of Djedkare Isesi.

Apparently, Djedkare Isesi’s expedition had brought a dancing dwarf entertainer back from Punt. Pepi II, then eight, very much wanted a dwarf of his own. In a letter to the expedition leader, Harkhuf, Pepi II expressed that he was far more excited to see the dwarf than he was for all the tribute.

This is one of several scenes from the funeral complex of Sahure, showing a naval expedition. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Forgotten, rediscovered, forgotten again

Following the end of Pepi II’s reign, the Old Kingdom collapsed. A changing climate left the region temporarily dry, leading to famine, worsening political instability. Egypt collapsed into multiple decentralized and intermittently warring regions. Massive trade expeditions fell by the wayside, and Punt was half-forgotten.

This chaotic First Intermediate Period eventually settled back down under the 11th dynasty, beginning the Middle Kingdom era. Around 2000 BCE, Pharaoh Mentuhotep III sent a trading voyage to Punt, reopening the route, or perhaps forging a new one.

His official, Henu, traveled across the desert from Koptos (now Qift) to the Red Sea, along a route called the Wadi Hammamat. From there, he sent ships out of the port of Wadi Gawasis. The ships made it to Punt, loaded up on myrrh, and came back. Mentuhotep III was so proud of the success that, as pharaohs were wont to do, he had someone carve it in stone and park the stone along the Wadi Hammamat.

Throughout the subsequent 12th dynasty, regular trade with Punt continued out of Wadi Gawasis. Myrrh and other aromatics were an especially important product of Punt because they served in religious rituals.

But boat-building is a privilege afforded only to those with access to timber. When Egypt broke apart again around 1630 BCE, foreign Hyksos kings ruled the north, and therefore the timber trade out of the Levant. No more timber, no more Punt.

A model of a rowed vessel from the 12th Dynasty, 1981–1975 BCE.

Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Hatshepsut expedition

One of the most famous Ancient Egyptian rulers, the Pharaoh Hatshepsut, was notable not only for being a woman but for being a great builder who led Egypt into a period of prosperity. She accomplished this, at least partially, through her expedition to Punt.

When she took the throne, it had been at least 200 years since the last Egyptian voyage to Punt. The end of the Middle Kingdom, the chaotic Second Intermediate Period, and the beginning of the New Kingdom had left Wadi Gawasis abandoned, the harbor filled with silt, and their trade routes forgotten.

Enter Hatshepsut. After the death of her husband-brother Thutmose II, she became regent for her young son-nephew, Thutmose III. A few years into her “regency,” she gave up the pretense and adopted the full title and regalia of a reigning monarch.

In the ninth year of her rule, according to inscriptions at her temple, Hatshepsut heard the voice of an oracle: The great god Amun-Re himself instructed her to search for the lost Punt and reforge the path to the land of myrrh.

Alternatively, she saw it as a way to continue her program of expansion without the logistical complications of conquering (and then ruling) land outright. Egyptologist Pearce Paul Creasman proposed this interpretation, describing Hatshepsut’s exploration missions as an attempt to legitimize her power.

Either way, she sent a great fleet, declaring, “I will lead the army on water and on land, to bring marvels from God’s land to this god.”

An image from her temple shows Egyptian soldiers marching off to Punt at Hatshepsut’s command. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Glimpses of Punt at Deir el-Bahri

The expedition appears to have gone swimmingly. Nineteenth-century British expeditions looking for trade routes were usually lucky to escape with their lives, but the Ancient Egyptian trade expeditionaries returned successfully and heavily laden with riches.

Lavish illustrations and inscriptions, preserved on the walls of Deir el-Bahri, Hatshepsut’s massive mortuary temple complex, tell the story of her expedition.

Hatshepsut chose a man named Nehsi to lead. Nehsi was a high court official of Nubian (a kingdom mostly encompassed by modern-day Sudan) descent, serving as her chief treasurer.

His expedition comprised five ships, all 21 meters long, carrying a force of 210 men. They also brought a large statue of Hatshepsut to put in Punt once they arrived, though whether this was intended as a gift or more of a flag-planting is ambiguous.

The relief wall in Hatshepsut’s funerary complex shows ships traveling to and returning from Punt. Photo: Creative Commons

In addition to their large statue, the Egyptians brought “bread, beer, wine, meat, fruit, and everything found in Egypt.” In exchange, they got a wealth of luxury and exotic goods: myrrh, whole living myrrh plants, other aromatics, gold, ebony wood, leopard skins, baboons, cattle, monkeys, hounds, eye paint, and slaves.

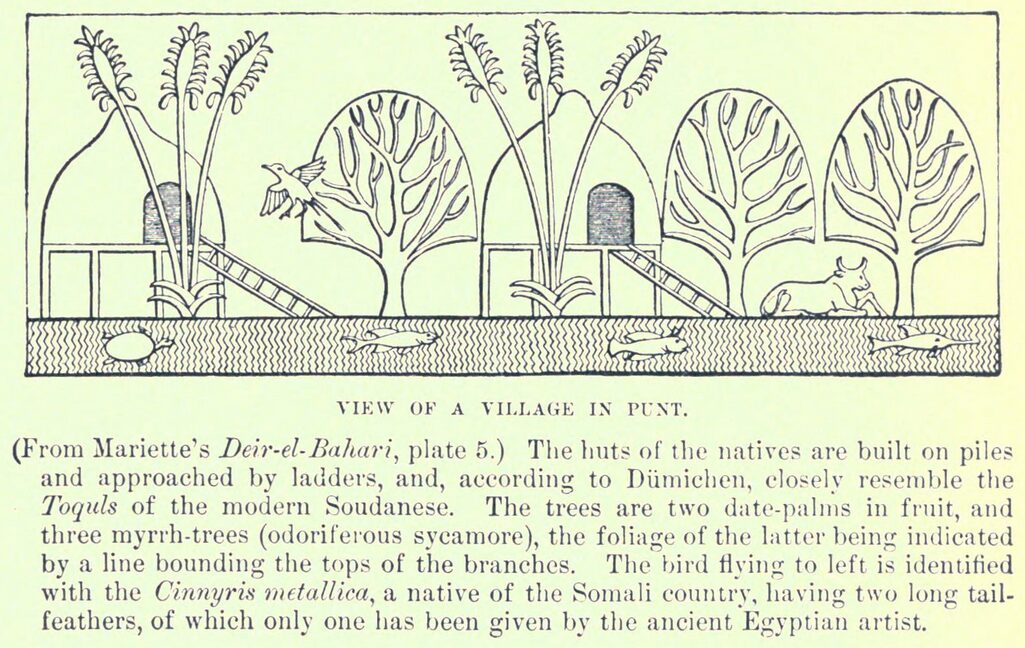

The relief showed the land of Punt populated by giraffes, rhinos, ibexes, donkeys, and birds, with ebony and date-palm trees. Puntite houses were round huts on stilts. What the relief wall doesn’t show, however, is how exactly they got to Punt.

This shriveled stump proclaims to be the remains of a myrrh tree, brought back from Punt and planted at Deir el-Bahri. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The rulers of Punt

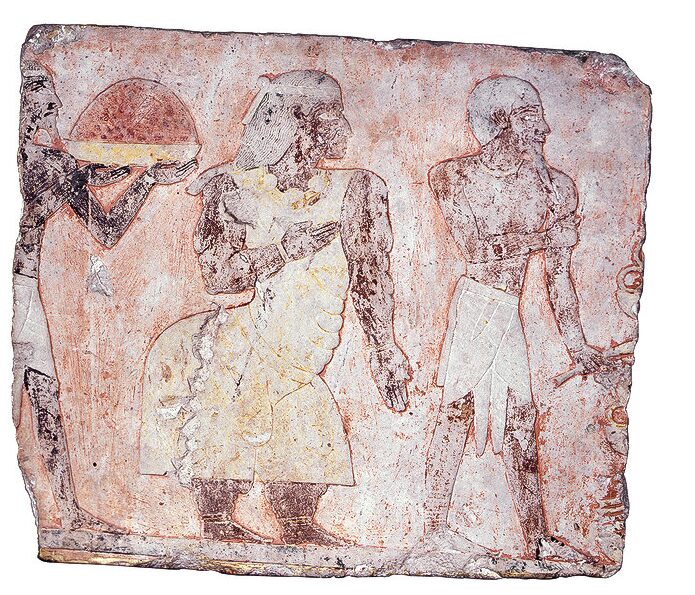

In Punt, Hatshepsut’s emissaries met with the king, Parehu, and his wife, Ati. Ati is depicted far outside the typical idealized norm in Egyptian art, with a wide lower body and rolls of fat. Egyptologists have debated why she is depicted this way. Is it an offensive or humorous caricature, a representation of a medical condition, or a stylized rendering of a normal, large woman?

Parehu, king of Punt, and his wife Queen Ati. Photo: The Global Egyptian Museum

Some even interpret it as a clue to Punt’s location. It may depict steatopygia, a type of build where substantial adipose tissue accumulates in the thighs and gluts. This build is found most frequently in the Khoisan people of Southern Africa and in some indigenous groups in Central Africa.

How to become a lost kingdom

The trade relationship that Hatshepsut established outlived her. In the 19th dynasty, another of the most famous pharaohs recorded an expedition. Ramesses II, known as Ramesses the Great, sent an expedition during his reign from 1279 to 1213 BCE.

An inscription in one of his temples records the king sending an expedition to Punt, which returned with incense and aromatic plants. As a result, “the marvels of Punt are secure, all the noble houses prosper.” Curiously, this inscription appears alongside a list of his conquests in Asia and the Middle East, not his conquests in Africa.

An inscription of Ramesses III provides more details. His great ships, heavy with Egyptian goods, were “sent to the great Sea of Muqed; [then] they reached the mountains of Punt without any misfortune befalling them.”

On the return trip, having exchanged their Egyptian goods for Puntite, the merchant fleet sailed to ” the mountain of Koptos,” the same Nile port by the Red Sea from which Henu had sailed about 850 years earlier.

After this, we stop finding mentions of the kingdom of Punt as a real place. But it retained a presence in Egyptian culture into the Ptolemaic period. It was associated, though the sacred myrrh, with divinity, magic, and botanical splendor. Punt’s distance from Egypt made it an exotic and almost unreal land. Punt appeared in love poems, religious hymns, and popular fairy tales.

His fragrance has come from Punt,

And his talons are covered with resin,

But my yearning is toward you.— From a New Kingdom love poem

The myrrh tree produces valuable aromatic resin. Photo: Shutterstock

Arabia? Sri Lanka? Sudan?

When early Egyptologists (in many ways indistinguishable from graverobbers) heard of Punt as the land of perfumes, they immediately thought of the Arabian Peninsula. In the height of Victorian orientalism, they recalled the famous “perfumes of Arabia,” and that settled the matter. Then excavation began at Deir el-Bahri, uncovering the relief wall.

Based on the people, buildings, plants, and animals in the relief, archaeologists concluded that Punt must be somewhere in Africa. But whether this African kingdom was just south of Egypt itself, around the region of modern-day Sudan, or as far as the Horn of Africa, they weren’t sure.

We know that many expeditions took the route over the desert to the Red Sea coast by way of Koptos. But we don’t know where they went on the Red Sea from there. Further complicating matters, there seems to have been an overland route as well, via the Nile.

There are hundreds of conflicting details between the different accounts. Old South Arabian languages, for example, do not contain the letter ‘P’, making it unlikely they would have a kingdom named Punt ruled by a Parehu. Then again, Ramesses’ inscriptions describe it as part of the Asiatic territories, to the north and east. As soon as an academic raised their theory, another found a point to discredit it.

Locations for Punt include the Levant, Sinai and Eastern Desert, the upper Nile Valley, the Horn of Africa, eastern Africa, and southern Arabia. Based on a dubiously identified plant specimen, a few have even proposed that Punt was an island near modern-day Sri Lanka. Everyone else can at least agree that this is unlikely.

A line drawing of the Puntite village from a late 19th-century Egyptologist. Photo: Public Domain

The port of Wadi Gawasis

With the written record so tangled, archaeologists have increasingly turned to physical evidence. We still have not found any ruins of Punt itself, but we have found the port of Wadi Gawasis, where expeditions to Punt began.

Under Kathryn A. Bard and Rodolfo Fattovich, a joint American and Italian archeological project launched in 2001 to excavate and explore Wadi Gawasis. After nearly two decades of work, they confirmed that the site was the Middle Kingdom port and found clues to the location of Punt.

In one sealed cave, they found over forty sycamore wood boxes with inscriptions on the side. Like a modern packing slip, the inscriptions said the boxes contained “wonderful things of Punt.” They also found broken pottery made by the Ancient Ona people of the Eritrea region, and by the Neolithic Gash Group of modern-day Eritrea and Eastern Sudan.

A study summarizing archaeological finds at Wadi Gawasis and at the Horn of Africa found Egyptian artifacts on both the Red Sea coast of southwestern Arabia and on the coast of Somalia. Based on this and the textual evidence, the authors proposed that Punt may have included both sides of the Red Sea, which engaged in trade with each other.

In other words, Punt didn’t fit any one place because it was actually two places, closely connected by trade across the narrow strait.

Archaeologists found ancient ropes, preserved in a dry cave, at Wadi Gawasis. Photo: ISMEO

Baboon evidence

It wouldn’t be Ancient Egypt without some good mummies, and the Punt mystery is no exception. We don’t have the remains of any Puntites, but we do have something that came from Punt: a baboon.

Baboons are not native to Egypt. Yet the Egyptians considered them– specifically the hamadryas baboon– as sacred animals. For religious ceremonies, Egyptians imported large numbers of the animals, which they often mummified. Punt was an important source of baboons, which are native to both the Horn of Africa and parts of the Arabian Peninsula.

Hoping to shed light on the Punt question, a team led by Dartmouth researchers tested mummified baboons to see where exactly they’d come from. They used isotopic mapping to measure where the two specimens had been born and where they had moved during their lives.

One specimen had lived for many years in Egypt before its mummification, while the other had died only a few months or even days after arriving. But they both had been born outside the Nile Delta. By testing modern baboon populations and comparing, researchers narrowed down the two baboons’ birthplace to an area encompassing modern-day Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti. In other words, they were from the Horn of Africa.

To be honest, I find this thing deeply off-putting. Something about how human the top half of his face is, versus how snout-like the bottom is. Photo: Egyptian Museum of Cairo

Is the case of Punt solved?

All the evidence we have of the Kingdom of Punt comes from the Egyptians. And the inscriptions of Ancient Egyptian rulers were not always accurate regarding their successes. Ramesses II, for instance, put up inscriptions claiming his victory in the famous Battle of Kadesh. His enemies, the Hittites, also claimed to have won the battle of Kadesh. Considering they were the ones who got to keep Kadesh, I’d say Ramesses’ claims may be a tad inflated.

That’s all to say, archaeological evidence is key. Just because an inscription says 3,000 men sailed to the end of the earth, doesn’t mean they did. Archaeological evidence seems to point to the Horn of Africa. That’s what most Egyptologists consider the most likely location.

That doesn’t mean we’ve found Punt. It means we know where to start looking.