In Australia, when they say “you’ve got Buckley’s chance,” it means you have little to no chance. This is ironic, considering that ex-convict William Buckley managed the impossible: Buckley escaped from a prison sentence, survived the Australian wilderness, integrated with an Aboriginal tribe, and received an official pardon for his crimes.

Background

Buckley was born in 1776 into a farming family in Cheshire, England. The details of his early life are not known, except that he was sent to live with his grandfather at a young age. This was probably an economic decision because his grandfather was able to provide him with a decent education and an apprenticeship.

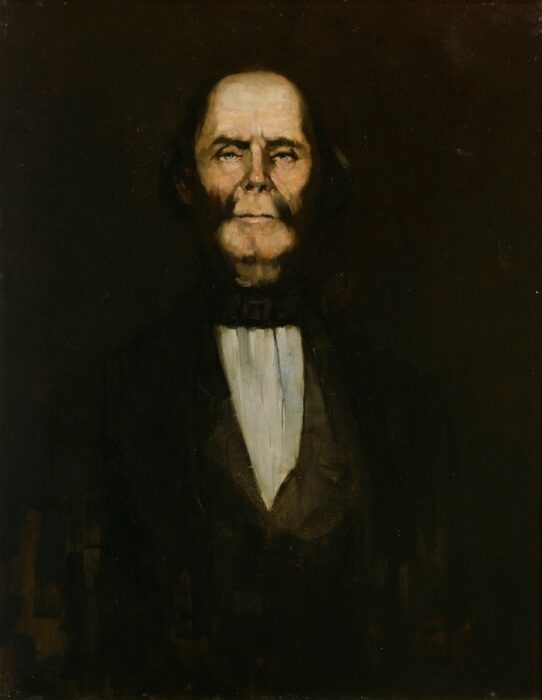

Buckley grew to a burly 6 feet 5 inches tall with bushy hair and eyebrows. Many considered him ugly due to a brief run-in with smallpox. At 15, he learned bricklaying, but seeking more adventure, he soon joined the military, first in the local Cheshire militia and then with the 4th (King’s Own) Regiment of Foot, which fought during the Napoleonic Wars.

According to some sources, authorities then caught Buckley stealing a bunch of cloth, though Buckley insisted he was carrying it for a lady. In 1803, the court sent Buckley to serve a 14-year-to-life sentence in the one place every Englishman dreaded: Australia. Since the American Revolution, Britain’s prisons had become overcrowded, and the newly settled continent needed a labor force.

Not dying here

The convicts and British officers sailed for the Pacific in the spring of 1803 on HMS Calcutta. Several convicts died on the way, but most of the 500 souls arrived safely in Sullivan Bay in southern Victoria in October. Convicts were now laborers who lived in huts and worked long hours in the sweltering heat. Not only did they have a very poor supply of fresh water and food, but they were also unable to construct decent houses. The trees were unsuitable building material, and the soil was inadequate. This wasn’t a life; it was a death sentence.

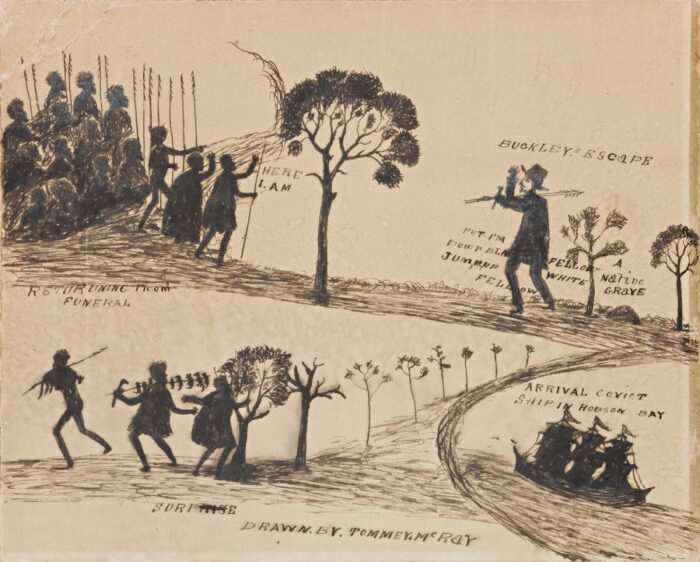

Illustration depicting Buckley’s escape and encounter with the natives. Photo: Tommy McRae

Buckley and a group of five convicts decided that escaping was their only chance to survive. They planned to go north to Sydney (then called Port Jackson). In December, the group took their chance during a deluge. They took what little food, water, and weapons they could find.

They kept to the coastline and ate shellfish, but their main problem was finding fresh water. During their journey, the thrill of freedom soon turned to desperation and doubt. Food ran out, and they were weak and delirious. Two men were recaptured, others perished or turned back, but Buckley was determined. For weeks, he hugged the coastline, scavenging for food and fresh water.

Finally, his luck turned when a group of curious Aboriginals found him and offered him a meal and shelter for the night. Buckley didn’t stay with them for long, probably out of distrust. He continued until he found a spear in a burial mound. He took the spear to use as a walking stick, which proved vital to his survival.

Time with the Aboriginals

Later, the Wallarranga tribe found him hunched over, starving, and exhausted. Because of his white skin, they believed him to be a spirit. Specifically, they thought he was the spirit of a tribal chief who had passed away. The spear Buckley carried belonged to this deceased chief. The tribe believed that the chief had lost his memory from his journey through the afterlife. They gave Buckley food, shelter, and a new name: Muuranong. This was the Chief’s name.

For Buckley, these people were strange. The English considered the Aboriginals barbaric, but Buckley inevitably became attached to this surrogate family, which treated him with dignity, respect, and kindness — far better than his own countrymen had. When the tribes fought, often over disputes over hunting rights, land, or women, the tribesmen made Buckley hide inside a hut with the women for safety.

Buckley recalled:

During 30 years’ residence among the natives, I had become so reconciled to my singular lot that, although opportunities offered, and I sometimes thought of going with the Europeans I had heard were in Western Port, I never could make up my mind to leave the party to whom I had become attached.

Adapting

Over time, Buckley adapted to their way of life. They taught him their language, traditions, and survival techniques such as hunting, fishing, skinning kangaroos, and roasting opossums. He lived among them for more than three decades, and he forgot most of the English language.

He adopted the Aboriginal style of clothing, wearing animal skins. Eventually, he became deeply respected as both a hunter and a mediator within their society. He was given a wife, and it was said he had a daughter with this woman.

William Buckley. Photo: State Library of Victoria

This new life among the Wallarranga was a dream for Buckley, but it came with consequences. Tribal warfare was unavoidable, and sudden death was a reality with which he had to live. Friends and members of his family died in conflicts with other tribes. These losses broke Buckley’s heart, and he headed back into the wilderness. He settled in the Breamlea area near a river and fished to survive. Eventually, some tribesmen found him and stayed with him for companionship.

Reuniting with the English

Until 1835, Buckley had no contact with Europeans. When some tribesmen told him of their plan to kill white men arriving on a ship, he convinced them not to attack. Instead, Buckley approached the Englishmen who had made camp on shore and tried to speak to them in his now broken English. The group was startled to see this wild white man with long hair wearing animal rags. After some tension, they managed to coax him into sitting down and telling his story.

Buckley’s story was so incredible that it earned him a pardon from Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur. Buckley then began a career as an interpreter and diplomat for the British government, while also advocating for peaceful relations and fair treatment of Aboriginals. His new life took him away from his hunter-gatherer lifestyle, but when he returned, the tribe would rejoice.

Joseph Gellibrand, one of the men who encountered him at their camp on the shore, recalled:

Buckley had dismounted, and they were all clinging around him and tears of joy and delight running down their cheeks. It was truly an affecting sight and proved the affection which these people entertained for Buckley.

Buckley eventually moved to Hobart in Tasmania and remarried. William Goodall, a local superintendent, described a gut-wrenching parting between Buckley and the Aboriginals:

When [Buckley] was taken away on the ship, the natives were much distressed at losing him, and when, some time after, they received a letter informing them of his marriage in Hobart town, they lost all hope of his return to them and grieved accordingly.

Buckley died in Hobart in 1856 after falling from a horse-drawn carriage.