This new ExplorersWeb series covers winter climbing areas around the world. Internationally known climbers, who honed their skills in their home ranges, provide the introduction.

Here, the young mountain guide and Piolet d’Or winner Tim Miller of Glasgow gives us a taste of the frost and “nick” of a Scottish winter.

“Scotland in winter is, as the cliché goes, the place to have big adventures in small mountains,” says Miller.

By adventure, he means an arctic-like experience that you should not underestimate, even though the highest peak in Scotland (and the UK) is Ben Nevis, at a modest 1,345m.

Is Nick there?

“The Scottish winter is pretty unique,” Miller told ExplorersWeb. “To begin with, the weather is pretty often bad, with frequent rain and blizzards. If someone wants to wait for a sunny, windless day, he might be able to go out very few days in the entire season. There is no choice but to gear up and be ready to face a good dose of bad weather.

“Second, we have a strong sense of climbing ethics here. No bolts or any other permanent protection is permitted,” Miller said. “Rather, we’ll use lots of the gear also used in summer like nuts, hexes, and things that you can hammer in, like lots of peckers, pitons…Cams are not so good because the cracks are usually filled with ice*.

Tim Miller demonstrates a pecker during the video chat. Photo: Angela Benavides

Early in the season, Scotland typically lacks water ice. That comes later, Miller says. Instead, there’s a peculiar kind of mixed climbing on very soft, thin ice. “That is, all white with hoar frost and rime,” explains Miller. “If you see the black rock, it’s not yet ready.”

Winter mixed climbing is always done on that shiny, silvery surface. Local climbers refer to a face in good condition for winter climbing as “in nick.”

“It’s also important to make sure that the turf on the rock surface is frozen as well, to prevent damaging it as much as possible,” Miller warned. “That requires cold conditions.”

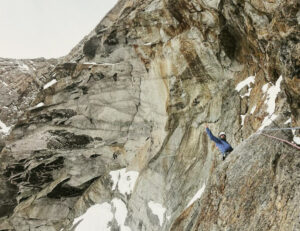

Mixed Scottish winter climbing. Greg Boswell with Robbie Phillips and Hamish Frost. Photo: Greg Boswell/Instagram

Weather: bad is good

For a visiting climber, Scottish winter climbing seems to require a lot of checking. Climbers from warmer locales (like this writer) might interpret its typical conditions as the right ones not to go climbing.

“Yeah, it’s kind of funny,” Miller admitted. “Often you spend the whole day inching every centimeter of marginal gain up the wall, and you need the entire day to complete a three-pitch route.”

Days are short at these northern latitudes, and most of the approach takes place while it is still dark. Snow and spindrift may make navigation difficult.

At least, the winter season in Scotland is extensive. Conditions can be great from November to mid-April but “it’s hard to predict,” says Miller. “This year, for instance, there were routes ready in October, but then we got a warmer spell in mid-December and the mixed routes disappeared quickly. Last year, November and December were great, then January was warm.”

Approaching a climb in northwest Scotland on a good enough day. Photo: Tim Miller

The Cairngorms, one of the most popular winter climbing areas, have a subarctic climate. Sometimes, blizzards are almost too strong to stand up in, and there are few physical references for orientation on the featureless plateaus.

Also, the climbing is so slow that it will likely get dark again before you finish. That means returning to the car in pitch darkness.

“In the end, you may have a 13-14 hour day only to climb three pitches,” says Miller, “but that’s why it is a big adventure although the mountains are small!”

Where to go

For Miller, Scotland has featured prominently in his learning process as a climber.

“It’s a great training field for higher objectives (such as the Himalaya) with trad climbing in summer and then winter climbing,” he said.

Miller on a new route in Foinaven, northern Scotland some weeks ago. Miller and Hamish Frost (author of the photo) covered “a large part of the very long and bleak approach through the darkness and the rain”…on mountain bikes. Read more on Miller’s Instagram post.

“Generally speaking, the west coast of Scotland has more mountaineering than climbing, while in the East coast is the opposite,” Miller said.

The most popular areas for winter climbing are in the Cairngorms. Some of its cliffs are relatively high so enjoy good conditions often. They are also relatively accessible from the park.

“Glencoe is also a great spot, and for water ice and gullies, the classic is Ben Nevis,” he says.

Have a look at the posts by local guru Hamish Frost, who is currently working on a book about the best climbs in Scotland. He recorded the video below by drone of Matt Pavitt on Fallout Corner in the highly popular northern Corries (Cairngorms).

According to many local climbers, the overall best place lies in Scotland’s northwest corner. It is becoming increasingly popular, despite its isolation. “But the best hard, mixed climbing is in Torridon,” Miller said. He also mentions the Isle of Skye.

Some more popular spots can get a bit crowded. This includes the northern Corries and, of course, the classic ice routes on Ben Nevis such as Point Five Gully or the 300m Orion Face. Check the video of its solo climb by Dave MacLeod, below.

In those places, you need to go with a backup plan because of the possibility of crowds. On the other hand, there are so many places in Scotland where you can spend the whole day on the mountain and meet no one at all.

Listen to the locals

Tim Miller is aware that the Scottish winter game may not be easy for foreign visitors. Things are much easier if we know local climbers, who are quite tuned in about when the routes are in proper condition.

“A great chance is the week-long winter meet that the British Mountaineering Council organizes every two or three years,” Miller suggested. “On these occasions, foreigners are paired up with climbers from the UK.”

The BMC organized the last meeting in 2020. (Below, a video of the international meet in 2014). Miller also noted the huts in Scotland are basic refuges, nothing like the civilized mountain hotels in the Alps. As for climbable conditions, Miller summarized his approach in one phrase: Make sure it is cold enough.