European Green Crabs have inundated part of the coast of British Columbia. To combat this invasive species, the Haíɫzaqv Nation, which manages the land, set up crab traps along all the beaches, baited with fish. In the last few years, though, the traps in the Bella Bella area have turned up with significant damage. So they set up cameras to catch the perpetrators.

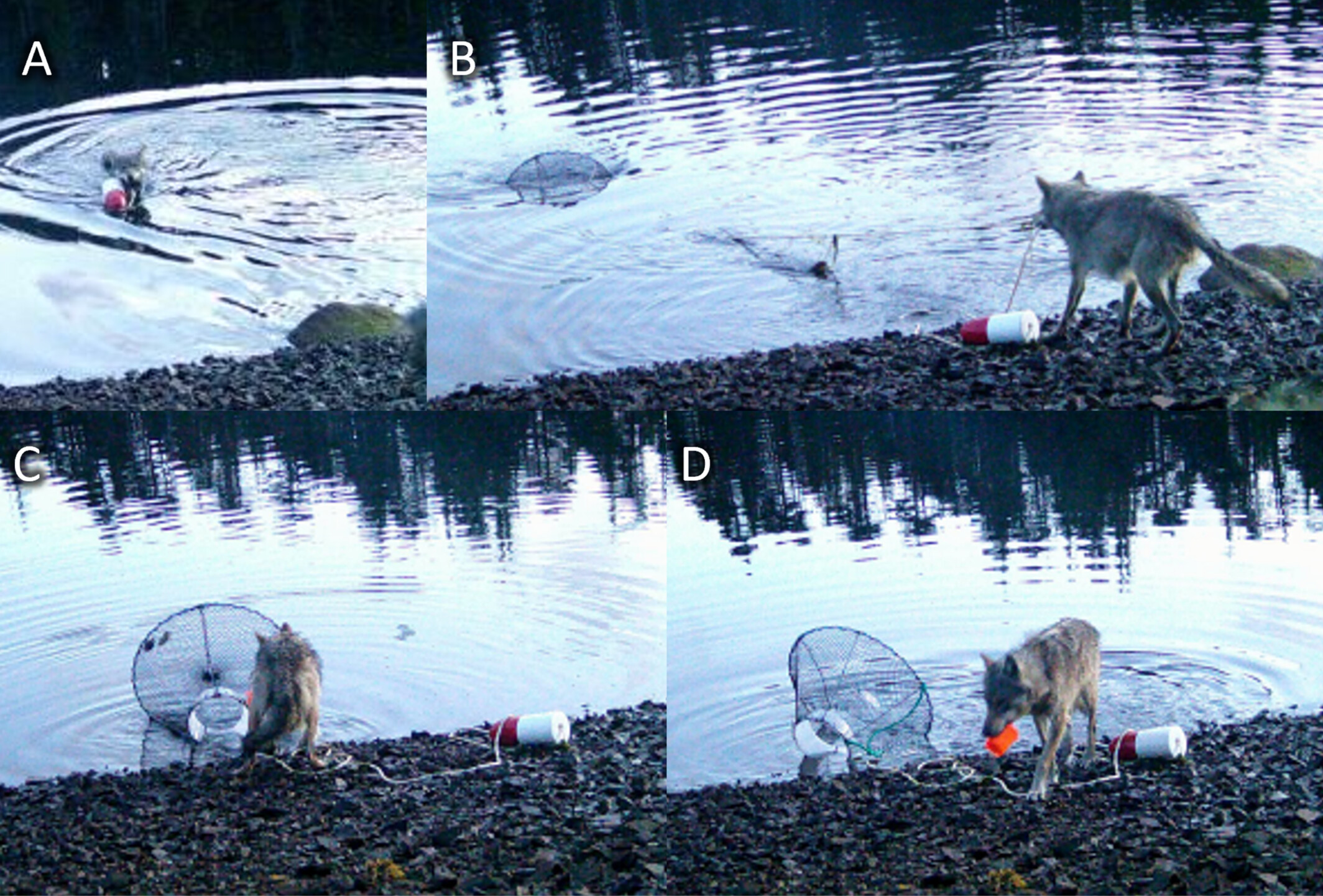

Almost immediately, the cameras caught remarkable footage of wild wolves feeding from the traps. A lone female wolf waded out at high tide and emerged carrying the trap’s buoy in her jaws. Then she pulled on the line to reel in the crab trap. Once the trap was on the beach, she tore open the netting and removed the bait cup, eating the tasty bait inside.

A new study explores the meaning of this behavior. Does this count as wolves using tools? How did they figure this out, the study asks, and just how much more common is tool use than we previously believed?

A wolf confidently trots toward a crab trap, which it knows holds food. Photo: Artelle et al

How did they learn this?

This is impressive behavior. It requires the wolf to connect and understand the relationship between a yummy fish treat, a rope, a buoy, and a (completely submerged) trap.

It was an efficient process, too. The whole affair took just three minutes. The wolf moved with purpose, clearly understanding the sequence in which she had to perform certain actions.

Researchers who studied the clips are still wondering how well the wolves really understand the mechanics involved in their trick. It’s possible, the paper suggests, that wolves learned to retrieve and open the traps through trial and error, then memorized the steps without fully understanding them.

It’s also possible they learned from watching people. When resource management officials stopped to check the traps and switch out bait, they could have inadvertently shown observing wolves how to retrieve traps. But officials raise the traps from a boat; they don’t drag them to shore.

We also don’t know how widespread this behavior is. Cameras did catch another individual retrieving a partially submerged trap, but so far, only the first female wolf has shown the ability to reel in a trap that’s completely hidden underwater.

Bait theft is a complex, multi-step process. This female wolf worked hard for that fish and I believe she deserved it more than the crabs. Photo: Artelle et al

The ‘tool use’ debate

Only rarely do researchers get a chance to observe wolf behavior in the wild. Is this level of sophistication common across wolves, and is this just the first time we’ve seen it? Thanks partially to the work of the Haíɫzaqv Wolf and Biodiversity Project, wolves in this area have minimal conflict with humans. Has their comparatively comfortable situation made them more confident and curious than other wolf populations?

The biggest question is more one of definitions, though. Namely: Does this count as tool use? Since tool use is considered a key marker of intelligence, categorizing wolves as a tool-using species would be significant.

The study cites “using an external object to achieve a specific goal with intent” as the common understanding. By this metric, the clip is definitely evidence of wolves using tools. But the most current comprehensive work on animal tool behavior (titled, creatively, Animal Tool Behavior) sets a higher standard.

“The animal must produce, not simply recognize,” this definition runs, “[the relationship] between the tool and the incentive.” So, if the wolves were tying ropes to the cages themselves, then it’d be tool use. Just using an existing rope doesn’t count.

Is it still tool use when animals appropriate human tools, rather than creating their own? The paper answers with an interesting analogy: The authors are writing their paper on a computer, “whose inner workings [they] do not fully understand.” Nevertheless, their use of this tool is certainly evidence of higher thinking.