Alchemy — the pseudo-science of turning base metals into gold, finding a cure-all elixir, or a potion for eternal youth — obsessed many pre-chemists of the Middle Ages. But not only men pursued these mysteries. Female alchemists became some of history’s earliest scientists. While chasing alchemy’s occult will o’ the wisp, they found cures to common ailments and designed apparatus that is still used in laboratories today.

Why did women gravitate toward alchemy?

Alchemy attempted to transmute ordinary metals like nickel and copper into valuable ones like gold and silver. However, its overarching goal was to attain perfection. Something called the philosopher’s stone was the magical key to this pursuits.

Women explored alchemy via medicine, cosmetics, “kitchen chemistry,” and religion, according to Sajed Chowdhury of Leiden University. They developed medicine and ways to better care for their families. They invented distillers to create ointments, fragrances, and other concoctions. It was alchemy in a domestic setting.

Alchemy carried an air of secrecy and mystery. “Secrets were a form of currency,” according to one author, by which one could acquire power and influence.

Nor was it just a medieval art. In the ancient world, perhaps the most notable female alchemists were Cleopatra the Alchemist, Mary the Jewess, and Hypatia.

Cleopatra the Alchemist

This Cleopatra was born in the 3rd century AD, 300 years after her more famous namesake died. Not much is know about her except that she lusted after gold, pursuing alchemy in the hope of amassing wealth.

Her single surviving text, the Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra, continues to baffle historians. It contains a series of cryptic symbols with very little context, including a snake devouring its own tail.

Historians believe that Cleopatra the Alchemist could have been a pseudonym or even a group of alchemists. In ancient Egypt, only the nobility practiced alchemy, suggesting that Cleopatra came from the upper echelons of society.

Whatever her identity, Cleopatra the Alchemist may have left behind a valuable apparatus called the alembic. This instrument consists of two vessels connected via a tube to distill liquids. It is still in use today, with modern modifications. However, some sources attribute the invention to Mary the Jewess or another alchemist.

Mary the Jewess

Mary the Jewess. Photo: Wikipedia

Mary the Jewess also lived around the third century AD. Her male contemporaries referred to her as Moses’ Daughter or Mary the Prophetess, although there is no record that she was even Jewish. Her background is a total mystery, except that she is credited as the first Western alchemist. She appears in the writings of other alchemical figures, like Zosimos of Panopolis, who describes her as a wise sage.

Mary specialized in creating laboratory equipment, new techniques, and new substances. She managed to produce silver sulfide and possibly discovered hydrochloric acid. She is credited with inventing the tribikos, another distilling apparatus. Additionally, she created the kerotakis, which collected vapors, and the water bath, sometimes called Maria’s Bath or bain-Marie — essentially a double boiler.

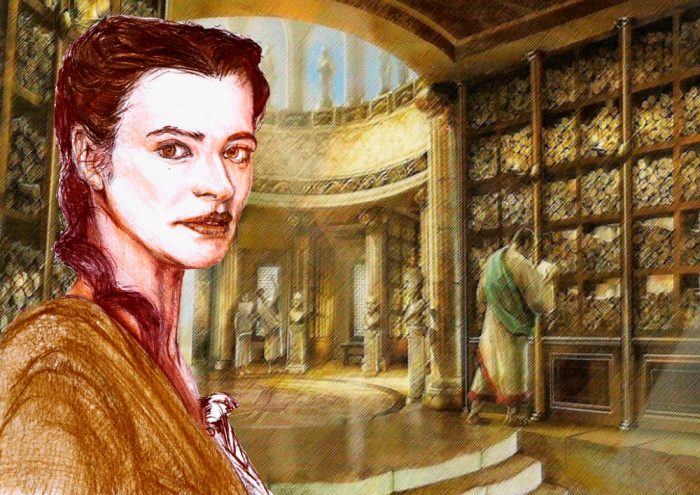

Hypatia

Around 350 AD, Hypatia lived, studied, and taught in Alexandria. The daughter of a mathematician and scholar, she took up teaching to people of all faiths.

A brilliant mathematician and inventor, she invented instruments for astronomy as well as alchemical apparatus like the hydrometer, which measured the density of liquids.

Isabella Cortese

Isabella Cortese published The Secrets of Lady Isabella Cortese in the mid-1500s. In it, she describes herself as a learned and well-traveled woman who has mastered alchemy.

Her book was popular with both sexes. Even Queen Elizabeth I took her advice on beauty and anti-aging techniques. She provided recipes for creating the philosopher’s stone, for dying one’s hair, detoxing, and even curing erectile dysfunction.

One example is a recipe for “face color” which calls for white-feathered pigeons, bread soaked in goat’s milk, silver, and gold.

Caterina Sforza

Caterina Sforza. Photo: Lorenzo di Credi

Caterina Sforza, the Countess of Forlí, had an affinity for cosmetics and medicine. She was highly educated in Latin and the classics. She had her own special herb garden for her experiments from which she produced fine fragrances and skin-lightening creams. Her manuscript Experimenti contained over 450 recipes for hair bleaching, treatment of wounds, and cures for fevers.

Unlike some women of the time, she did not hide her alchemical pursuits. Rather, her power and influence through a strategic marriage and political shrewdness added to the reputation of her alchemy skills.

Christina, Girl King of Sweden

Christina of Sweden. Photo: Sebastien Bourdon

Alchemy even enthralled royalty. Christina, the “Girl King” of Sweden, took an interest after meeting alchemist Johannes Franck. She examined the work of the Rosicrucians, an esoteric intellectual movement that combined metaphysics, mysticism, Christianity, and Hermeticism.

She hoped that Stockholm would one day become a center for learning, a sort of “Athens of the North.”