Everyone loves spiders. The only thing everyone loves more than spiders is a lot of spiders all in the same place. The only way this scene could be improved, popular opinion holds, is if the many spiders are in a pitch-black flooded cavern deep underground, which smelled like brimstone.

Well, fantastic news. A recent study unveiled a massive subterranean spider colony, with a gigantic communal web, living in a sulfuric cave on the border between Greece and Albania.

A female Tegenaria domestica perched on the massive spiderweb in Sulfur Cave. Photo: Urak I et al

Many individuals, several species

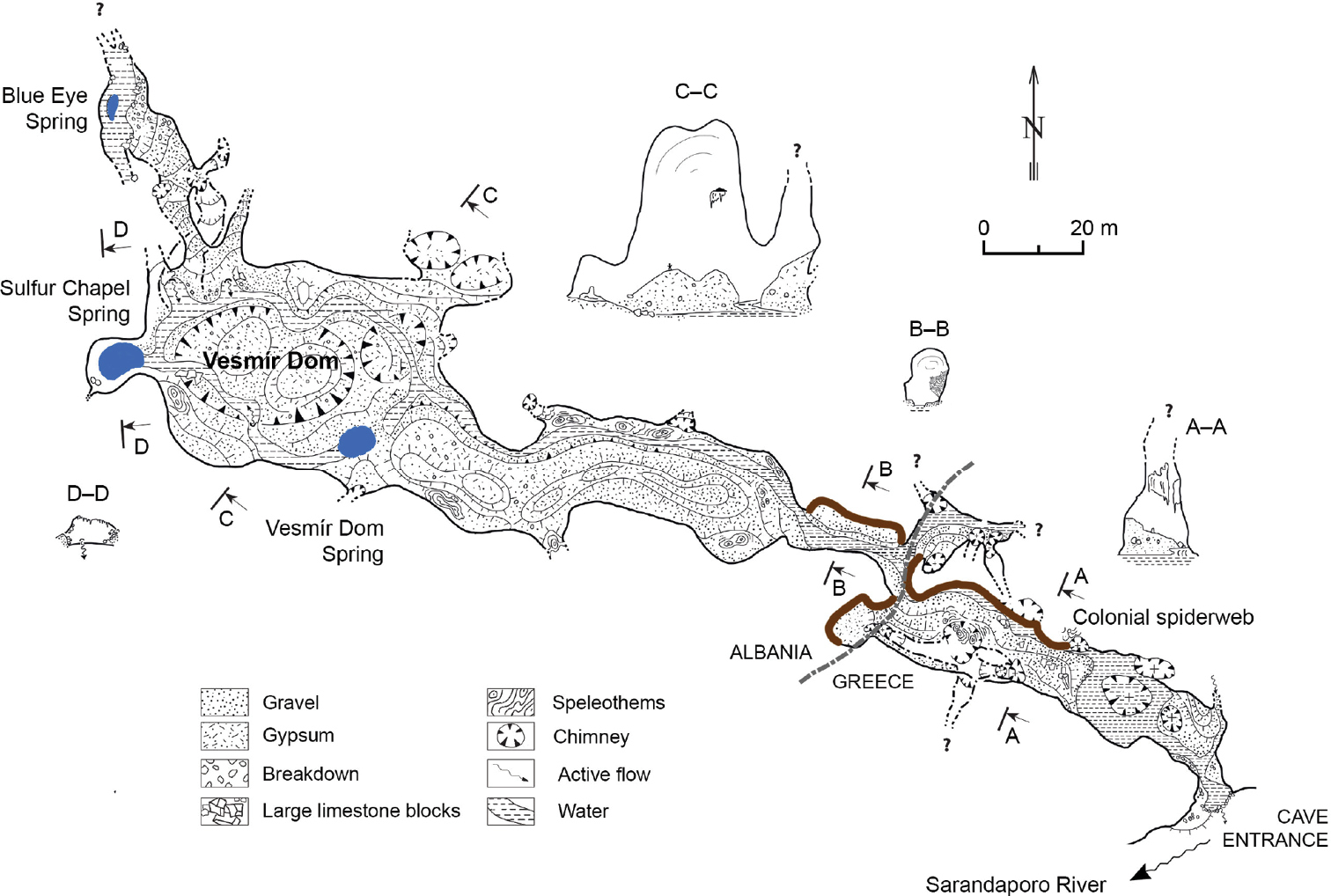

The world’s largest spiderweb (that we know of) occupies over one hundred square meters of surface area. Starting about 50 meters from the cave’s entrance, this region is permanently dark. The passage is narrow and low, and the bottom is covered by a sulfur-rich stream. Some sections of web have grown so heavy with silk and spiders that they’ve detached from the wall.

While the scene could have emerged from JRR Tolkien’s worst nightmares, the spiders themselves are not giant. In fact, the Arachnes who wove this tapestry come from several different species, working together over generations to build a veritable spider citadel.

The most populous are the Tegenaria domestica, or Domestic House Spider, some 69,100 strong. As suggested by their name, T. domestica often lives near humans. While they are considered endemic to Balkan caves, this is the first time they’ve been observed building large, colonial webs.

Their primary collaborators are approximately 42,400 Prinerigone vagans. Smaller than T. domestica, the research suggests that the lack of light prevents T. domestica‘s predatory instincts from triggering at the sight of their diminutive cohabitants. P. Vagans has also never been known to form colonies before.

Every square meter of the colony is crawling with somewhere between a few hundred and a few thousand spiders, 110,000 spiders in all. They are outnumbered, however, by their prey.

A map of Sulfur Cave, with the spiderweb section indicated in brown. Photo: Urak I et al

Why so many spiders?

These spiders are predators, and so they congregate wherever there is the most prey. The study, led by Istvan Urak of the Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania, estimated there were more than 200 small chironomid flies for every spider. A type of non-biting midge, around 2,414,440 individual Tanytarsus albisutus flies feed the attercop metropolis in Sulfur Cave.

This massive, dense swarm hovers above the sulfuric stream, which runs along the cave floor. This section of the cave represents a rare type of ecosystem, where life thrives without any sunlight.

In 2024, a team from the Emil Racovitza Institute of Speleology visited Sulfur Cave, following up on earlier reports of unusual animal abundance, including a massive spider colony. The team identified 30 invertebrate species living in a self-sustaining chemoautotrophic ecosystem.

Chemoautotrophic means the bottom of the food chain turns inorganic materials into energy, instead of using energy from the sun as plants do in most ecosystems. Microorganisms in the stream convert sulfur into energy-rich biofilm (slime) which is eaten by larvae. The larvae turn into insects (like the non-biting midge) which are eaten by the predators (spiders).

This unique lifestyle seems to be changing the traditionally surface-dwelling populations within it. In the 2025 study, Urak’s team genetically sequenced the P. Vagans and T. domestica in the cave. Both species were genetically distinct from nearby, above-ground populations.