Although whaling is an ancient practice, just how ancient it is and who the first whalers were, is unclear. But the discovery of the world’s oldest harpoon in southern Brazil has completely rewritten that hazy history.

Until recently, evidence placed the earliest whalers in the Northern Pacific Rim, the North Atlantic, and the Arctic. Groups like the Nuu-chah-nulth of Vancouver Island have been hunting whales for up to 4,000 years. By comparison, Inuit and their Thule ancestors in the Arctic have only hunted whales for about 1,000 years in their sealskin kayaks. The earlier Arctic people, the Dorset, did not have kayak technology and had no means of hunting whales.

But whale hunting seems to have begun in South America rather than North America. A new article reveals that the practice is at least 1,000 years older than we believed. And it was going on in Brazil.

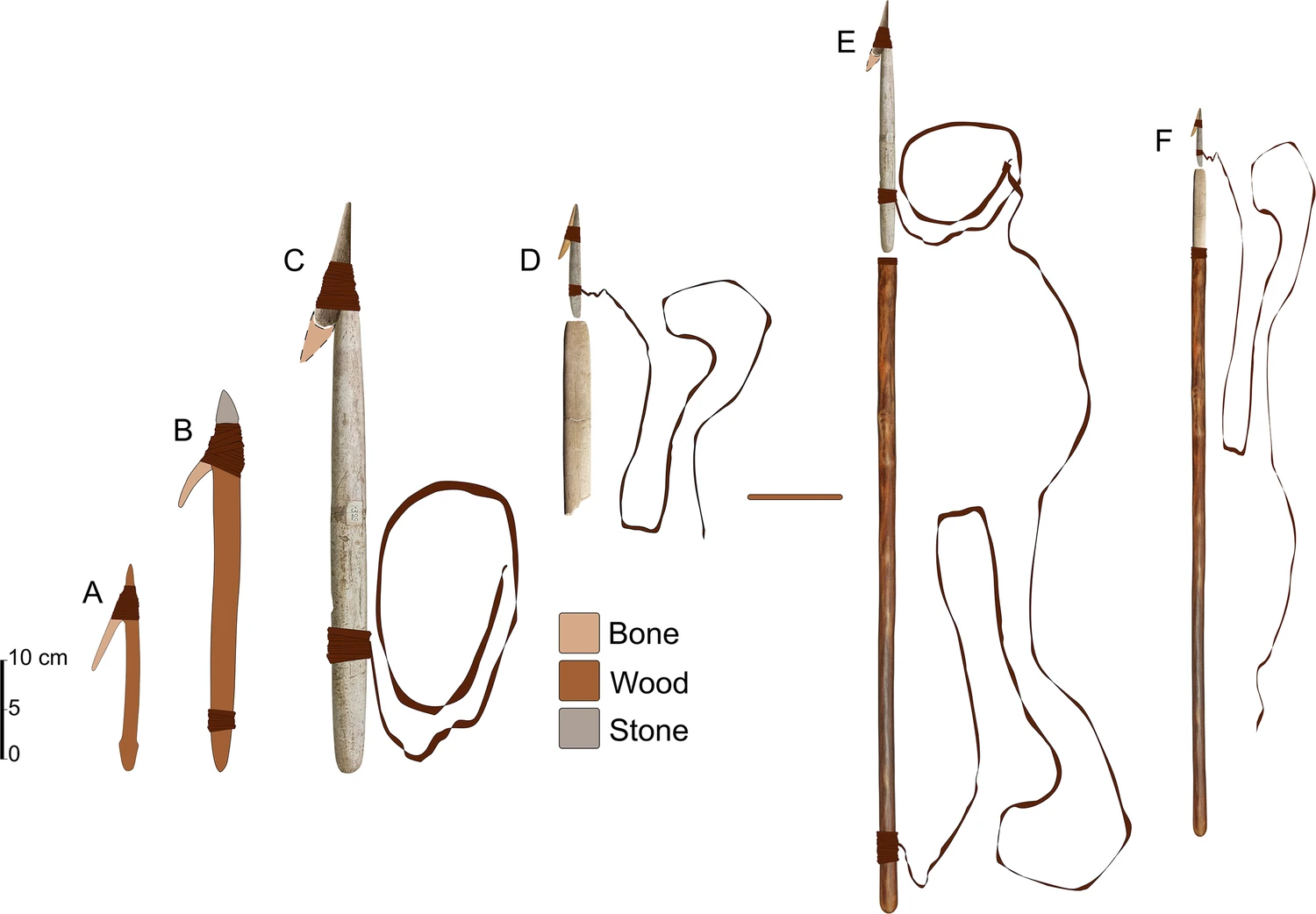

A reconstruction of the oldest known harpoons, from what is now Brazil. Photo: McGrath et al

Shell heaps

The southern coast of Brazil was once home to a group of people who left behind shell mounds called sambaquis. They vary in size and content, but their relevance here is that people used them as middens — i.e., trash heaps. And there’s nothing archaeologists love more than a good trash heap.

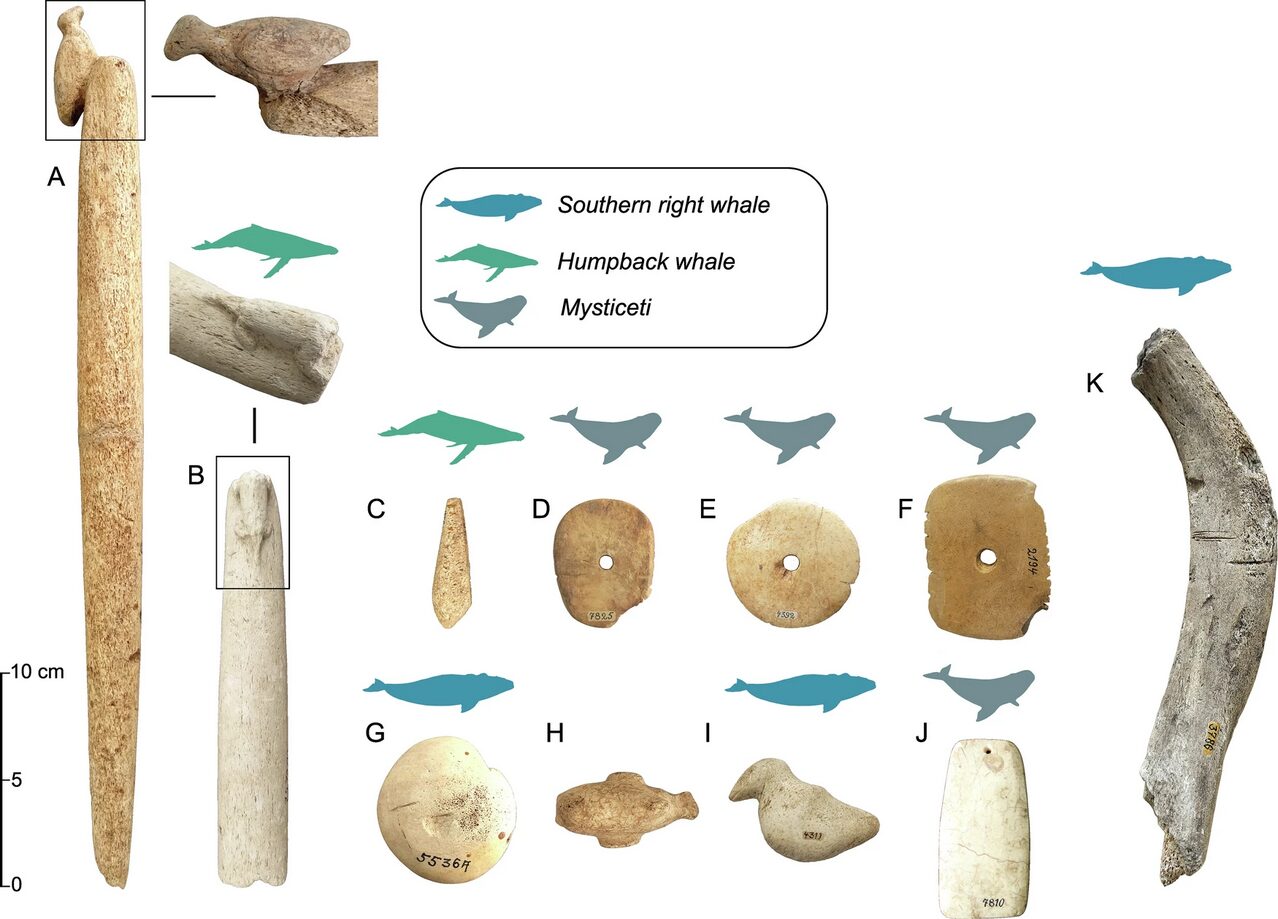

The team, led by Krista McGrath and Andre Colonese from Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, focused on sambaquis from Babitonga Bay. These contain hundreds of whale bone fragments and tools, which the team analyzed in depth. They were able to identify the remains of southern right whales, humpback whales, blue whales, sei whales, sperm whales, and dolphins. Many of them bore cut marks, showing that people had processed them with sharp tools.

Collections of whale bones, and evidence of people using whale materials, are not enough to prove a culture hunted whales. Upper Paleolithic sites around the Bay of Biscay, for instance, show that people there were processing and using whales, but whether they obtained them by hunting or by scavenging dead whales that washed ashore is unknown. In the Babitonga Bay sambaquis, however, archaeologists have a smoking gun. Or rather, smoking harpoon.

Some of the many artifacts made of whalebone, found in sambaqui sites. Photo: McGrath et al

The whalers of 5,000 years ago

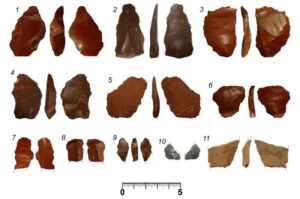

They found over a dozen ancient harpoons, or parts of them, from three different sites. A wooden foreshaft was fitted with a bone barb and sometimes a sharp stone point. These parts would have been joined with sinew or fiber lines.

Radiocarbon dated to over 4,900 years ago, these tools prove whale hunting beyond a doubt.

“These communities had the knowledge, tools, and specialized strategies to hunt large whales thousands of years earlier than we had previously assumed,” said Katie McGrath, the study’s lead author, in a press release.

Whaling and whalebone materials seem to have held high cultural significance. Whalebone products have turned up in graves and as part of funerary monuments. These ancient whalers also carved cetacean remains into elaborately worked artifacts, like 19th and 20th-century whalers did scrimshaw — designs and images etched into a sperm whale’s tooth. Whalebone objects likely had ritual significance, the sort of item that would be buried with someone.

The evidence also shows the distribution of the whales before industrial hunting. Humpback whales were once common much further south than they are currently. As their population recovers, they may move southward, back into their old haunts.