In a remote stretch of northern Quebec, scientists have uncovered pieces of Earth’s crust that are more than 4 billion years old. These ancient rocks, from the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt (NGB) rock formation, are the oldest-known rocks on the planet.

Geologist Jonathan O’Neil from the University of Ottawa found the rocks with his research team in 2008. He and his team proposed that the rocks were 4.3 billion years old. This made them Earth’s oldest rocks, which formed just a few hundred million years after the Earth itself, in what is called the Hadean eon.

Other scientists weren’t convinced. Different studies and dating methods placed the rocks between 3.3 and 3.8 million years old. Since then, their age has been the subject of much debate.

O’Neil has now spent over a decade studying these rock formations. His new study looks at intrusion rocks from the NGB. They formed as molten magma cut through existing layers of rock and hardened. Two separate dating methods suggest the intrusion rocks are indeed 4.16 billion years old.

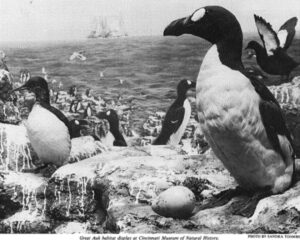

Christian Sole, Hanika Rizo, and Jonathan O’Neil, co-authors of the new study, stand on the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt in northern Quebec. Photo: Jonathan O’Neil

Hell on Earth

They formed as the molten magma pushed its way through the volcanic rock that was already there. This means the volcanic rock must be older than the newly studied intrusion rock.

“The intrusion would be 4.16 billion years old, and because the volcanic rocks must be older, their best age would be 4.3 billion years old, as supported by the 2008 study,” O’Neil explained to Reuters.

Both sets of rock came into existence during the Hadean eon, the geological period between 4.5 and 4 billion years ago, when the Earth was new and resembled a ball of molten lava. The period is named after Hades, the Greek God of the underworld. At that time, the planet was hot and violent, a hive of volcanic activity with surface temperatures of around 230˚C — typical pizza-baking temperature.

Originally, researchers did not believe there was much rock formation during this era, but recent evidence suggests otherwise. Even during this chaotic and witheringly hot time, Earth had started to form a solid crust. This means that conditions for life could have started far earlier than we used to think.

“These rocks and the Nuvvuagittuq belt being the only rock record from the Hadean, they offer a unique window into our planet’s earliest time to better understand how the first crust formed on Earth and what were the geodynamic processes involved,” said O’Neil. “Since some of these rocks were also formed from precipitation from the ancient seawater, they can shed light on the first oceans’ composition…and help establish the environment where life could have begun on Earth.”

Close-up view of the volcanic rocks dated at 4.3 billion years old. Photo: Jonathan O’Neil

A rare find

Finding rocks this old is almost unheard of. Most of Earth’s original crust has been recycled by plate tectonics or worn away by erosion. These rocks offer a unique window into what the planet was like over four billion years ago.

The NGB lies within Inuit land near the town of Inukjuak, and the growing interest in the rocks is starting to worry the local community. All further rock sampling in the area has been paused, partly due to their concerns about preserving the land. Previous scientific studies have damaged the area, with large chunks of rock being removed.

“There’s a lot of interest in these rocks, which we understand,” said Tommy Palliser of the Pituvik Landholding Corporation. “We just don’t want any more damage.”

They want to put protections in place that would allow research using only non-invasive techniques.