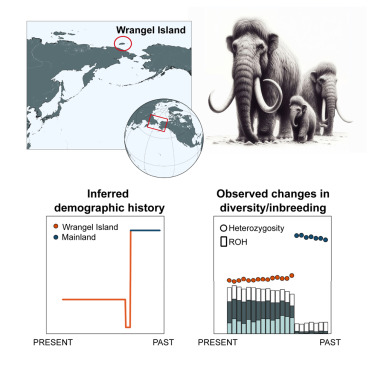

Ten thousand years ago, as the Pleistocene ended and the Holocene began, sea levels rose and trapped a small group of woolly mammoths — possibly as few as eight — on Wrangel Island off the Siberian coast.

What happened next is what science calls a “bottleneck event.” It’s when a species faces a combination of a tiny population and external factors like environmental pressures, disease, or hunting. Meanwhile, the genetic variation thought to be necessary for a species to recover drops below a minimal threshold.

Many scientists believe that such bottlenecks spell the end of a species — an increasing concern given the planet’s accelerating biodiversity loss.

But, as a new paper in the journal Cell demonstrates, the Wrangel Island mammoths might provide some hope for modern species.

A mammoth tusk in a Wrangel Island streambed. Researchers analyzed genetic data from 21 mammoths — including 14 from Wrangel Island — for their new paper. Photo: Shutterstock

How? Well, although the Wrangel Island herd eventually died off, they made it another 6,000 years on their desolate island, eventually reaching a population of 200 to 300.

Four thousand years ago isn’t all that long ago in the vast scale of history. It’s remotely possible that the last Wrangel Island mammoth took its final breath as the capstone of the Great Pyramid of Giza was lowered into place. The point is that woolly mammoths were around for a long time.

More importantly, genetic research conducted by the paper’s authors indicates that it was an unrelated disaster — likely something related to a changing climate, disease, or both — that ultimately spelled doom for the Wrangel mammoths, not inbreeding.

Bottlenecks, genes, and mammoths through the centuries

To reach their conclusions, the scientists studied genetic information from 21 woolly mammoths, including 14 post-bottleneck individuals from Wrangel Island. The data spans some 50,000 years — especially valuable given how difficult it is to study long-term changes in modern endangered species.

It turns out that the genetic changes weren’t powerful enough to cause a population meltdown, i.e. mutations that prevented the mammoths from breeding or caused them to die out. In fact, something of the opposite may have occurred.

A graphic from the paper published in the journal ‘Cell.’ Image: Marianne Dehasque et al.

“Rather than accumulating high-impact mutations, the Wrangel Island population underwent a gradual purging of such mutations,” they note in the paper.

“As a consequence, the last surviving mammoths on Wrangel Island had fewer high-impact mutations compared with the ancestral mainland population,” the scientists continued.

Hope with a side serving of caution

In addition to offering a new toolset to scientists monitoring genetic diversity in contemporary endangered species, the paper serves as both hope and warning for the Earth’s current biodiversity.

On the hope side, the Wrangel Island mammoths seem to prove that recovery from a bottleneck is possible (they share this story with cheetahs, which also bounced back from a bottleneck around the same time).

On the other hand, the Wrangel Island herd did eventually succumb to some kind of disaster. Researchers point out that it’s possible the original bottleneck event — and the limited genetic variation that followed — may have still contributed to the herd’s eventual extinction, especially if disease was involved.