In 1914, explorer Fitzhugh Green shot and killed his Inuit guide Peeawahto. Green was a member of the Crocker Land Expedition, which set out to find a mysterious island that Robert Peary allegedly spotted off northwestern Ellesmere in 1906.

The expedition leader, Donald MacMillan, had been north once before, as one of Peary’s assistants. An ambitious man, MacMillan hoped that the discovery of Crocker Land would make his reputation. The expedition was affiliated with the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH).

Expedition leader Donald MacMillan. Photo: Library of Congress

The published account of the murder had always seemed strange to me. In a storm on northern Axel Heiberg, Fitzhugh Green’s dogs are buried and die. Peeawahto won’t slow down for Green, who is on foot. Green, convinced that he is being abandoned, shoots Peeawahto in the back, appropriates his team, and rejoins the others. MacMillan’s laconic summary of the event: “Green, inexperienced in the handling of Eskimos…had felt it necessary to shoot his companion.”

Searching for clues

Except for one brief detour, I’ve covered the Crocker Land Expedition’s entire route from Greenland to the northern tip of Axel Heiberg. In particular, to better understand the murder, a partner and I manhauled 700km to the scene of the crime near Cape Thomas Hubbard. I then visited Bowdoin College in Maine and the AMNH in New York to look over the expedition journals.

Bowdoin College has Green’s journal. Between the tattered brown covers and pemmican stains, fear lurks between the grandly penciled lines. Green would write some forty books in his life, all bad. But the journal is, at its key moments, unaffected. It shows a man overwhelmed with panic.

MacMillan’s journal is in New York.

“Not our favorite topic,” commented the librarian when I asked for Crocker Land material. “Wasn’t someone killed on that expedition under museum auspices?”

At the AMNH, I found the photo of Peeawahto that heads this story.

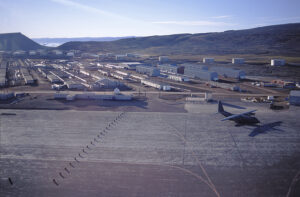

Where MacMillan and his men overwintered in Greenland. The two huts are modern hunting cabins. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

The expedition begins

The Crocker Land Expedition overwintered in Greenland. The following February, with an army of 19 men, 15 sleds, and 165 dogs to lay depots, MacMillan set out for northern Axel Heiberg and the Arctic Ocean.

As they advanced and laid down supplies, all of MacMillan’s party turned back to Greenland except MacMillan, Green, and two Inuit, Etukashu and Peeawahto. Peeawahto (Piugaattoq, in modern orthography) had previously served with Frederick Cook, as well as with Peary and Knud Rasmussen, who described him as “a comrade who was ready to make personal sacrifices in order to help and support his companions.”

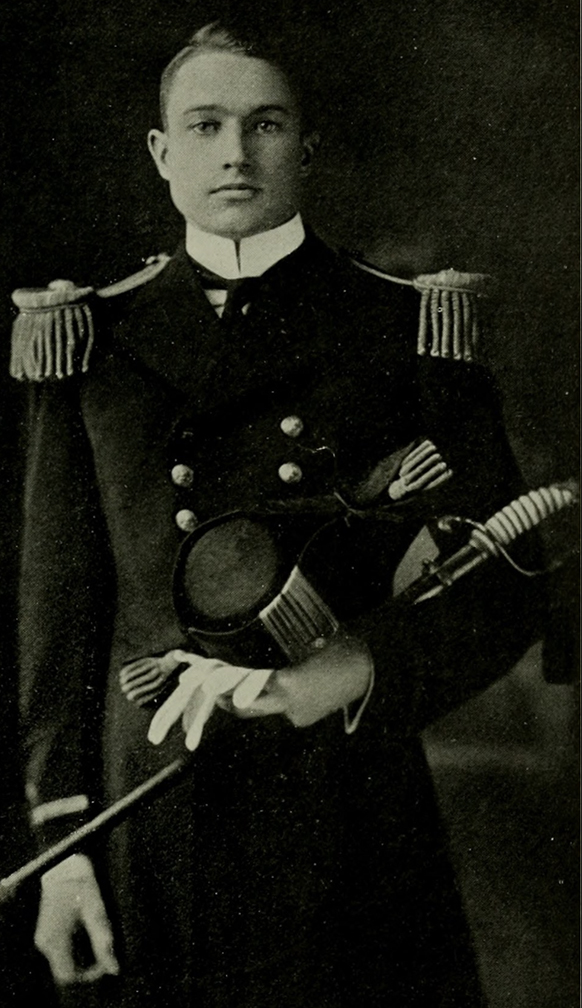

Fitzhugh Green as a naval academy graduate. Photo: Wikipedia

Fitzhugh Green, a 25-year-old naval ensign, came from good old stock. His great-great-grandfather had been a large Virginia landowner in the 1600s. As a young man, he was talkative and ingratiating, with a tendency to fawn over his betters –- and he expected those whom he considered his inferiors to defer to him. This made his dealings with the Inuit condescending at best.

Cringeworthy

MacMillan and Green fancied themselves the dauntless explorers leading the happy-go-lucky, childlike Eskimo. Green’s posturing, in particular, was cringeworthy:

“Their life was a sublimely simple fight for food and clothing,” he wrote later. “Mine was a cruel struggle of such labyrinthine intricacy that only the genius could be rich and none be truly contented save the shrewdest philosophers.”

Spring weather is usually good on Ellesmere, but 1914 featured one gale after another. Fighting the north wind was exhausting. Once Green fell asleep chewing his supper. They couldn’t spot wildlife in the blowing snow. Dogs died, and men went hungry. Worried entries about the worn-out dogs recur daily in Green’s journal.

A good spot for a murder

Eureka and Nansen Sounds separate Ellesmere Island from Axel Heiberg Island. As you move up Eureka Sound into Nansen Sound, the high ice cap of Axel Heiberg tapers to low hills. Western storms can now deposit their snow on upper Nansen Sound. The very names reflect the moister climate. Ellesmere’s Black Mountains yield to the White Peninsula.

The mood changes, too. Even in a gale, Eureka Sound feels protected. But as Nansen Sound opens into the Arctic Ocean, there is nothing but exposure. It is the wildest place I’ve ever seen, a good spot for a murder.

On April 14, MacMillan, Green, Etukashu, and Peeawahto struck northwest across the Arctic Ocean toward the hypothetical Crocker Land. Incredibly, they managed to travel 250 kilometers offshore, but of course, they found nothing. There was nothing to find.

A mirage of land over the Arctic Ocean at the very spot on northern Ellesmere Island where Peary claimed to have seen Crocker Land. But a mirage would not have fooled the experienced explorer. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

“I could plainly see that the Eskimos were discouraged,” MacMillan confided in his journal. “Peeawahto did not like the looks of so much open water so late in the year.”

As they headed back to land empty-handed, Green and MacMillan walked to lighten their load. Etukashu and Peeawahto rode, as Greenlanders always did.

They hurried to reach Cape Thomas Hubbard at the northern tip of Axel Heiberg, averaging 50km a day. They touched land on April 28.

A fateful assignment

Since Crocker Land didn’t exist, MacMillan must have felt pressured to bring back as many extras as possible. So although the dogs were exhausted and Peeawahto and Etukashu were impatient to get home, he proposed a four-day split-up.

He and Etukashu would cross Nansen Sound to revisit old Ellesmere cairns. Meanwhile, Green and Peeawahto would close the ring on Axel Heiberg by covering its last unexplored section, the fifty kilometers between its northern tip and latitude 80°55′ on the west coast. Here they were to retrieve Sverdrup’s 1900 cairn message. “All the adventurous blood in my veins boiled up at the prospect,” wrote Green later.

Looking for Sverdrup’s cairn at 80˚55′ on northwestern Axel Heiberg Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Sverdrup’s end cairn has eluded the handful who have looked for it over the last hundred years. It is a great prize. In it, Sverdrup left a note declaring sovereignty over the arctic islands for the King of Norway.

On one manhauling trip, my partner and I spent a day and a half scouring the shoreline for it. We focused on the north side of a small, unnamed bay, which most closely matched Sverdrup’s description. Sverdrup and one of his men spent hours building the cairn. It must have been sizeable, but in an open landscape where nothing manmade escapes notice, we found no trace.

A blizzard hits

Green and Peeawahto never got that far. Shortly after separating from MacMillan on April 29, 13km southwest of Cape Thomas Hubbard, the worst storm of the year hit. It became so violent that Peeawahto quickly built a small igloo near shore, and they sheltered inside it.

Near the scene of the crime. The 1906 Peary cairn atop the northern tip of Axel Heiberg Island. The murder took place below and to the left. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

For the next two days, Green’s journal becomes almost raving. Their stove doesn’t work. Drifting snow keeps plugging their igloo’s ventilation hole. “I was about done for,” he writes. “It was black as night in the hole.”

The next day, April 30, the wind drops a little, and they go outside and dig out Peeawahto’s sled. Green claims that his own sled and dog team are “under 15 to 18 feet of hard-packed snow,” so he gives them up for lost. “We cannot move yet, although to stay here is almost suicidal,” he says.

Retreating to the igloo, they try to melt snow for tea but have more trouble with the stove. “P. refused to make a hole in the roof…The fumes made us both sick, and I vomited several times.”

Conflict and murder

In the early hours of May 1, the wind briefly dies, and Green wants to continue to Sverdrup’s cairn. Peeawahto refuses, saying that MacMillan had instructed them to proceed just one day down the coast.

“I told him that I was master now until we got back to Mac,” says Green, although the argument becomes academic when the storm rises again, and they have to retreat to the igloo.

A little later, they begin their retreat with the one dog team. Green walks to keep his feet warm, but he cannot keep up with Peeawahto, who rides the sled. The storm picks up yet again. A panicking Green orders Peeawahto to slow down. To emphasize his point, he takes the rifle off the sled. But a few minutes later, Peeawahto begins to pull away again.

I fired once in the air, but he kept on. Then I fired twice, knocking him off his komatik. The dogs stopped. I ran up and found the man unconscious. I lashed him onto the komatik…

I must have wandered about for six or eight hours trying to find a familiar landmark. Finally I recognized a rock on the shore and headed for the igloo…

I finally got the snow cleared out somewhat [and took] P. in first. When I tried to do something for him, I found that he was dead.

The situation is an unhappy one. Here I am in a howling blizzard with a dead Eskimo, a strange team, and a few soaking or frozen garments…

Fitzhugh Green during the MacMillan expedition.

Heroic posturing

Green’s later accounts fill in some details that his journal omits. The murder weapon was Peeawahto’s .22 Savage. At the first shot, Peeawahto slumped against the sled’s upstanders. “As the dogs did not stop, I thought that possibly he might still be alive so I shot again, splitting his head open so that his brains fell out.”

With a macabre presence of mind, Green removed Peeawahto’s kamiks –- his own footwear was falling to pieces. They didn’t fit. Green couldn’t stand the dead man’s eyes staring at him in the igloo, so he dragged the corpse outside and left it behind an ice block.

He continues his heroic posturing: “I kept wanting to say, ‘Peeawahto, you lucky dog, it’s all over for you. For me, it’s hundreds of miles of hell, with all the pain and misery of hell, and not one degree of its heat!’ But I wouldn’t let myself say it. I was afraid of being afraid.”

Green retreated the next day toward Cape Thomas Hubbard with Peeawahto’s team. The storm had also forced MacMillan to abort his journey, so he and Etukashu were camped nearby. “Mac, this is what is left of your southern division,” announced an exhausted Green when he pulled up on May 4, driving Peeawahto’s team.

“Good God, Green, is Peeawahto dead?” asked MacMillan.

Scared for his life

Green sketched out the story. Etukashu knew some English and overheard their conversation, but scared for his own life perhaps, he appeared to accept their explanation that Peeawahto had died in an avalanche.

“Etukushu took the news of his friend’s death very complacently,” wrote Green, “and was pleased with Peeawahto’s kamiks, which I brought.”

The wind continued to roar over Eureka Sound on their homeward march. On May 20, they reached their cache on eastern Ellesmere, just 50km across the frozen sound from Greenland.

“What a wonderful day,” wrote Green, “all surprises!…We found the box of supplies: sweet chocolate, marmalade, canned pears and peaches, hash, and a can of corn. My, we were happy!”

Back in Greenland, they continued to maintain that Peeawahto had died during the storm. Thanks to Etukashu, the villagers knew better but said nothing. At least one member of the Crocker Land Expedition was disgusted.

“[Green] did not consider it murder,” wrote their doctor, Harrison Hunt. “Peeawahto was just a savage…I would have to live with and care for a man who had killed my friend…I found my anger hard to control.”

MacMillan unsympathetic

Even MacMillan was unsympathetic. “[Green’s] assertion that if he had permitted the Eskimo to escape with the sledge, dogs and food, he would have starved, is not a sufficient reason for killing one of the best Eskimos I have ever known.”

After his return to America, Green continued to show the total lack of shame that was his greatest asset. In a 103-page article for a naval publication, he prefaced the murder with paragraph after paragraph of poetic babble: “Every sense has its pleasurable side. Sight loves beauty. Hearing revels in music. For touch there is sensuous softness and smoothness…”

His description of the shooting itself is no less surreal. “He that had loomed hostile and a deceit between me and safety lay now crumpled and inert in the unheeding snow…I had baffled misfortune. The feeling sent red gladness to my anemic humor…The present was perfect, ecstatic… I laughed, not fiendishly, but because I was glad…”

Aftermath

Green never went back to the Arctic after 1917, but his four years in the White North allowed him to affect an explorer’s persona for the rest of his life. He lectured widely on his experiences. Many of his books and articles play up those arctic years. He wrote of “my friend Etukashu” and how “I lived with the natives for almost four years, so I know how wonderful they are.” At the same time, casual references to “darkies” and “small brown people” continued to make their way into his godawful prose.

Always a talented sycophant, Green was aide to an admiral, to the president of the Naval War College, and to book publisher George Putnam, for whom Green wrote a gushing biography of Robert Peary. He followed with a biography of yet another arctic faker and establishment hero, Richard Byrd.

The incident does not seem to have harmed Green personally or professionally. He died in glory and honor, and his jottings and family photographs are now preserved at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.