In June 2006, three men shouldered packs heavy with food, light on everything else, and pointed themselves across the empty wilderness of northern Alaska. Their goal was simple — to walk as far as possible with no resupplies, caches, hunting, or fishing, just their clothing and equipment, willpower, and the calories they could carry.

Roman Dial, an Alaskan backcountry legend and now retired Professor of Biology and Mathematics at Alaska Pacific University, called it the longest wilderness walk in America by fair means. With him were Ryan Jordan, a gear obsessive from Montana and publisher of Backpacking Light, and Jason Geck, an Alaskan adventurer and a Professor at Alaska Pacific University. They named the project the Arctic 1000, a nod to the kilometer count if they made it all the way.

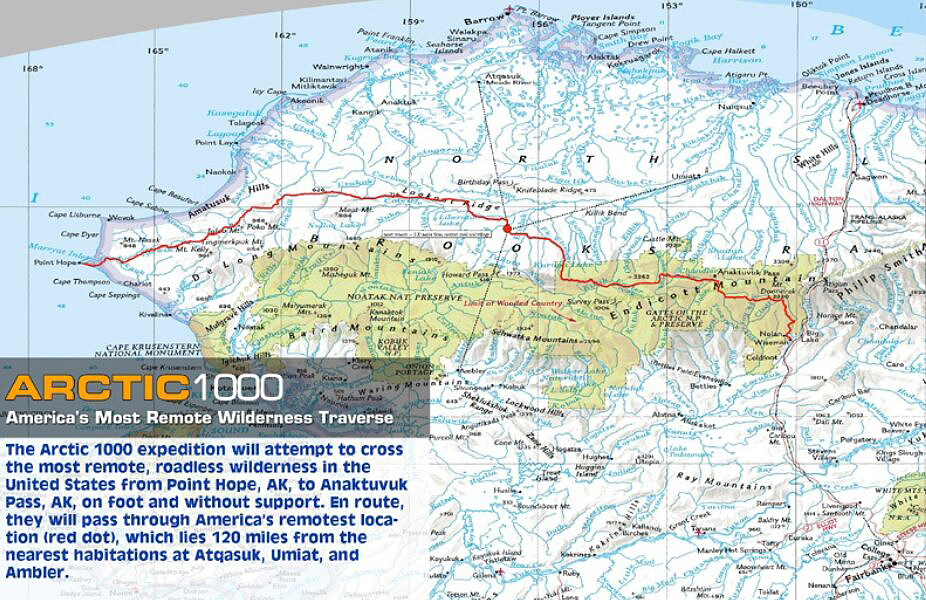

The Arctic 1000 route. Photo: Ryan Jordan

Their line began at the Chukchi Sea on Alaska’s western coast and ran east through the Brooks Range to the Dalton Highway, around 1,000km with no resupply. Along the way, it crossed America’s most remote point, roughly 190km from the nearest road or habitation. They carried everything they needed on their backs with zero foraging and zero outside help. Dial started with about 25kg, using ultralight gear to keep his base weight to around 7kg.

Dial finished after 1,000km and 23 days and 8 hours. Jordan exited earlier due to injury, and Geck left on day 21 due to prior commitments. That evening, Geck and Dial slept in a hotel, and he and Geck ate in a restaurant, trading some remaining food for a cheeseburger. Dial pushed on to do the final 113km in a day and a half with his now very minimal pack.

The equation of maximum range

Dial had been wrestling with the “how far, how fast, how heavy?” puzzle since Alaska’s early wilderness races and his days as a mathematics grad student. Back then, he noticed a harsh truth: Every extra half-kilo on his back cost him roughly a kilometer a day. Lighten the load, and you could go farther. Add weight and you’d slow down, no matter how fit or hardened you are.

Roman Dial is a well known alpine climber, adventure racer, and wilderness traveler and was instrumental in the birth of modern packrafting. Photo: Roman Dial

That observation eventually became a mathematical model, thanks to Dial’s skills with numbers. It’s simple enough to scrawl on the back of an envelope and is built from three pieces:

- Effort (MAX): How far you could walk in a day with nothing on your back.

- Comfort (b): your base gear weight.

- Food ration (f): how much food you need each day.

Subtract your Max effort from your comfort load, and you get what Dial calls your Animal Factor (A).

That number is the “engine” you bring into the field. From there, some further math can be used to work out the furthest distance you can cover before the balance between food weight and walking speed tips against you.

A worked example

Take a hiker who can cover 50km in a day with no pack. Their Max is therefore 50. Let’s say their backpack and gear excluding food (what Dial calls comfort) weigh just 5kg, and they plan to eat 0.7 kg of food per day. This hiker’s Animal Factor would be 45 (50-5).

Dial filled his water bladders with high-energy foods like olive oil and almond butter. Photo: Roman Dial

Dial’s subsequent formulas can be used to estimate out how far this hiker can cover as well as how many days it might take him.

- Maximum distance possible = Animal Factor squared, divided by four times the daily food.

452/(4×0.7) = 723km - Time to walk that far = Animal Factor divided by twice the daily food.

45/(2×0.7) = 32 days - Food carried at the start = Animal Factor divided by two.

45/2 = 22.5kg. - Total starting pack weight = base gear plus that food.

5 + 22.5 = 27.5kg.

So, this hypothetical hiker, starting with a 27.5kg pack, could theoretically walk about 723 km over 32 days, an average of 22.5km per day.

If the same hiker increases his food from 22.5kg to, for example, 40kg, he will be out there longer — 57 days — but cover less ground, only 286km, an average of 5km/day.

Testing the theory

The Arctic 1000 was the ultimate test of that theory. The first week was hard, thanks to comparatively heavy packs, knee-deep tussocks, and cold river crossings. Every evening meant cooking on a wood stove or open fire, a tarp staked low against the wind, and a shared sleeping quilt for two of the three.

Dial and partners cooked over wood fires to avoid having to carry fuel. Photo: Roman Dial

Their diet was also quite minimalistic. Olive oil in soft bottles, almond butter, chocolate bars, ramen, and mashed potatoes. Each man carried close to 100,000 calories worth of food and planned to burn thousands from their own bodies. Dial, then 45 years old, lost around 6.5 kilograms over the course of the walk.

A careful balance

Carry more food, and they may have been too weighed down. Carry less, and they would not have been fueled adequately to maintain their pace. Somewhere in the middle is that razor’s edge where wilderness travelers can walk the farthest with what they can carry.

Dial’s initial calculations and aim for himself was to walk 850km in 17 days. The Arctic 1000 confirmed this was possible and a little more. Of course the model doesn’t factor in psychological factors, and it only crudely estimates physiological capacity.

A tired-looking Jason Geck. Photo: Roman Dial

For Dial and his companions, that razor’s edge stretched across northern Alaska. It wasn’t just about walking a thousand kilometers; it also helped to test if Dial’s maths could be lived out in practice in the backcountry. It was about answering the question that had intrigued Dial since his wilderness racing days. How far can a person go on nothing but what’s on their back? One thousand kilometers later, Roman Dial had his answer.