A couple of weeks ago, the North Pole/Barneo ice camp season fizzled out, leaving disappointed skiers, marathon runners, and champagne tourists. Environmentalists have pointed out that the whole idea of Barneo is out of date. Because while tractors and huts are parachuted onto the sea ice, they are not removed afterward. They are just left to drift, eventually breaking through the ice over summer and littering the bottom of the Arctic Ocean.

But not always. Before the climate started warming and when the Arctic Ocean ice was a lot thicker, ice near the North Pole drifted toward Greenland. And the ice sometimes even reached Cape Farewell, the southern tip of Greenland. It then continued to drift up the West Coast.

Once, in 1965, the ice brought a surprising bounty to some hunters in Greenland. There was no Barneo in those days but there were floating Soviet ice stations not far from the North Pole that were its predecessors.

Period painting of De Long’s ship, the Jeannette, trapped in the ice. Photo: Wikipedia

A tragic learning experience

Our understanding of how the Arctic Ocean currents worked came accidentally out of an exploration tragedy. Between 1879-1881, American George W. De Long tried to reach the North Pole by sailing his ship, the Jeannette, north of the Bering Strait. The Jeannette soon became trapped in the ice and was eventually crushed off the Siberian coast.

George W. De Long. Photo: Wikidata

De Long’s crew tried to haul sleds over the ice to safety in Russia, but 20 men, including De Long, died along the way.

Three years later, to everyone’s surprise, wreckage from the Jeannette turned up off the southwest coast of Greenland, near Qaqortoq.

The wreckage of De Long’s ship, carried on the sea ice from Russia, turned up at Qaqortoq in 1884, three years after the ice had crushed it. Eighty years later, the remains of an old North Pole ice camp was retrieved just a little further north, at Arsuk.

This serendipitous discovery gave the polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen an idea. He built a walnut-shaped ship called the Fram that would ride up when the ice floes squeezed it rather than be crushed. In 1893, nine years after the debris appeared off Greenland, Nansen froze the Fram into the ice off Russia, hoping to drift to the North Pole and then beyond to Greenland.

They didn’t quite get there, but Nansen and the Fram survived. And the concept, based on the drift of the Jeannette wreckage, was brilliant.

Fridtjof Nansen contemplates the Fram, safely frozen into the ice. Photo: National Library of Norway

Multiyear ice

What Greenlanders call Sikorsuit (Big Ice, commonly called multiyear ice in English) from Sikuiuitsoq (the Arctic Ocean) was a regular visitor to Southwest Greenland in the 1960s. It was so solid, it could have floated all the way north to Sisimiut or further.

When these giant rafts of ice floated past in early summer, it was like a seal buffet, a Greenlandic happy hour that left folks stuffed and happy. Polar bears also rode this icy express, which is how they made rare appearances in southern Greenland.

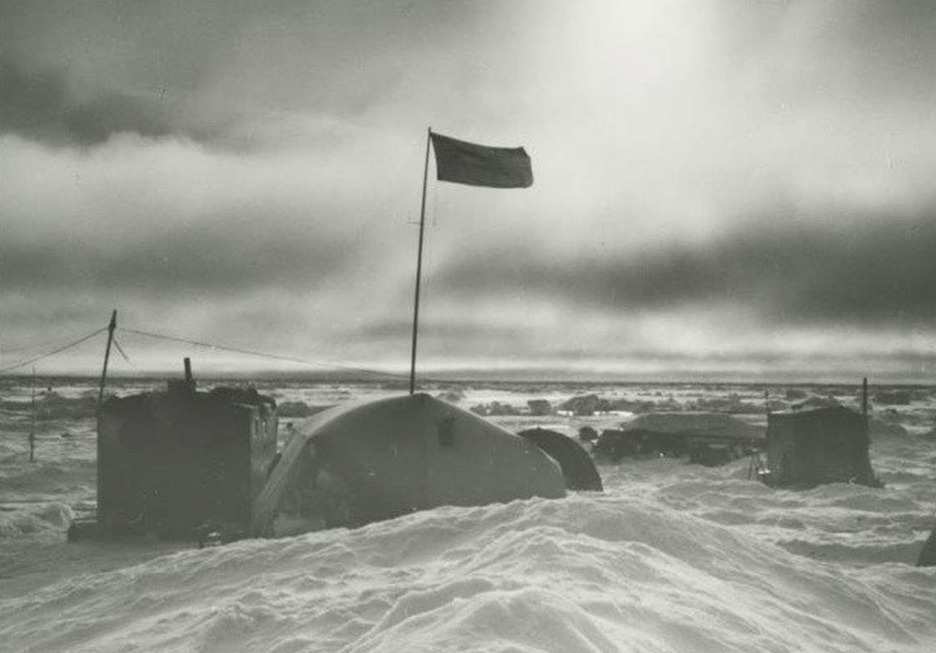

On that memorable day in 1965, locals near the town of Arsuk rubbed their eyes in disbelief. There were huts floating past on the ice. And the huts were intact.

Arsuk, Greenland in the 1960s. Any extra buildings and barrels of oil were welcome. Photo: Greenland TV

Alfred Jakobsen, a childhood friend of my Inuit husband Ole Jorgen, remembers when some family members were out on a casual seal-and-polar-bear grocery run when they stumbled upon these mysterious huts. Given the scarcity of a Home Depot in Arsuk, they snagged the huts and towed them back to Arsuk. Meanwhile, the multiyear ice continued its northward journey.

Jakobsen’s uncle, Julius, says that he was the one who first saw the huts. He described them as “fine houses on top of a huge ice island.” The huts were intact. According to him, there were five huts, four meters by five meters each.

The huts had an abundance of weather equipment in them and obviously belonged to some drifting polar station. Russian knickknacks inside confirmed that it was almost certainly one of the old Soviet SP (Severny Polyus/North Pole) stations that preceded Barneo.

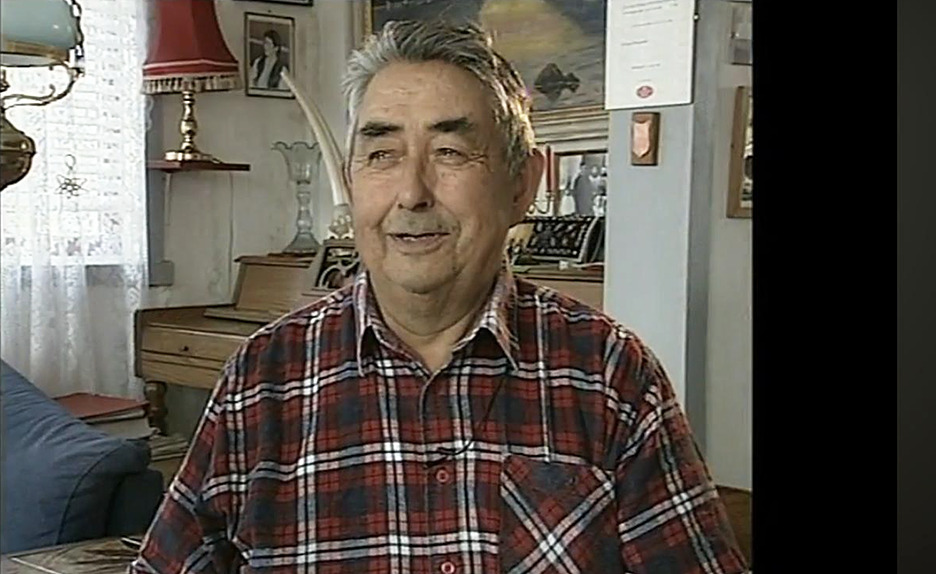

Julius Jakobsen, who first found the huts from the North Pole ice station. Photo: Greenland TV

More huts

Some say that later that summer of ’65, a second pair of huts drifted by. The Greenlanders had now snagged seven huts in all. Some speculated that the second huts came from a U.S. drift station called Arlis-2. Arlis-2 floated on a piece of ice shelf that broke off from northern Ellesmere Island. However, the timing doesn’t work on this theory, since Arlis-2 was only abandoned in 1965. Its icy platform would have taken at least another year or two to make its way to southern Greenland. But wherever it came from, it was a bounty.

Unfortunately, no photos exist of those repurposed huts, although there is a photo of one of the Arlis-2 structures on its original ice island, below.

Hut on Arlis-2.

Greenlanders, Ole Jorgen says, could teach a masterclass in “reuse, recycle, or else.” Nothing goes to waste — not food, not wood, not even a lonesome plastic bottle. Everything’s fair game for a second act, keeping nature spick-and-span for the future generations.These huts were not only useful shelters, they had barrels of oil in them. The local people found those particularly valuable.

Here’s hoping the leftovers from Barneo 2024 likewise make it to Greenlandic shores once again. But with Silaannaap allanngoriartornera — climate change — the sea ice is thinner and melts faster, so southern Greenland doesn’t get those faraway visitors any more. Yet this year, the big ice has already popped by Qaqortoq, so fingers crossed — maybe, just maybe, reuse is in the air.