For many, 6,814m Ama Dablam is one of the most beautiful mountains in the Himalaya. Located in the Khumbu Himal, its name means “Mother’s Necklace.” It is sometimes called the Matterhorn of the Himalaya.

Today, we examine the classic 1996 ascent by two Slovenian climbers and the mountain’s broader climbing history.

Ama Dablam. Photo: Shutterstock

The first attempts

The first attempt on Ama Dablam was in the autumn of 1958. Led by Alfred Gregory, the team included Dick Cook, John Cunningham, and Cyril Levene from the UK, and Piero Ghiglione and Giuseppe Pirovono from Italy. Gregory’s team eventually abandoned their climb on the southwest ridge at around 6,000m because of the difficult rock and ice.

A few months later, in the spring of 1959, Brit John Hubert Emlyn Jones led another expedition to the peak. Emlyn Jones’ team included George Fraser, Mike Harris, Frederick Sinclair Jackson, Nea Morin, Ted Wrangham, and two Nepalese sherpas, Annulu Sherpa and Urkien Sherpa. According to the American Alpine Journal, the group climbed the hardest part of the northeast ridge, largely thanks to the efforts of Harris and Fraser.

On May 21, Harris and Fraser left high camp at 6,400m. They climbed a large ice tower across which they had already cut steps the day before. Their team watched from below until Harris and Fraser disappeared from view, ascending toward the summit. It seemed likely they would make the first ascent of Ama Dablam, but the pair disappeared and were not seen again. The Himalayan Database indicates that the team’s highest point was above 6,500m.

Ama Dablam. Photo: Maik Psotta/Wikipedia

The first ascent

Two years later, in the spring of 1961, Edmund Hillary led an expedition to Ama Dablam. The group included American Barry Bishop, New Zealanders Michael Bedford Gill and Wally Romanes, and Michael Ward from the UK. The team targeted the southwest ridge.

On March 13 at 2 pm, Bishop, Bedford Gill, Romanes, and Ward reached the summit.

Many years later, on Jan. 26, 2004, Emlyn Jones, the leader of the 1959 party, sent a letter to Richard Salisbury at The Himalayan Database.

“Michael Ward who made the first complete ascent on Ama Dablam, having seen our photographs, is fairly certain that Mike [Harris] and George [Fraser] reached the summit and were probably lost on the way down,” Emlyn Jones wrote.

Two weeks later, Ward also wrote a letter to Salisbury. “I reckoned that Mike Harris and George Fraser were good enough climbers to have climbed Ama Dablam by their route. That’s why I made this remark. [But] we saw no signs of them on the summit,” Ward concluded.

Michael Ward in the Khumbu region during the 1951 Everest reconnaissance. Photo: James Milledge/The Himalayan Club

Ama Dablam statistics

Until the end of 2023, 1,525 teams had attempted Ama Dablam. A total of 5,715 climbers summited and 34 people died on the peak. Of the 1,525 teams, 95% targeted the southwest ridge, considered the normal route.

The first ascent of the northwest face

On Oct. 1, 1980, the Tokyo Himalayan Expedition led by Yasuji Kato arrived at Ama Dablam. They established a base camp at 4,700m on the west shore of the lake east of Duwo village. The team included Hisao Fukushima, Seiji Ogawa, Yoshifumi Teranishi, Masaaki Tomita, and Tadao Tsuboi.

The Japanese party started the route on a dangerous couloir from the Duwe Glacier and climbed in traditional style. The couloir was very exposed to avalanches. On October 6, Fukushima fell 100m and had to go to the hospital in Periche. Later, Kato was hit by an ice serac and needed two weeks to recover.

The team set up a temporary camp 1 in a snow hole at about 5,300m but did not use it much. The team described the face as dangerous but not difficult. They couldn’t progress for several days because of snow slabs and falling ice. The weather improved beginning October 20 and they set up a new camp 1 at 5,900m on October 23.

Ama Dablam’s upper section. Photo: Tomaz Humar

Tomita and Fukushima made the first summit attempt on November 7 and almost reached the top before turning back in strong winds. The next day, the two climbers topped out. The rest of the team followed, with Kato and Tsuboi summiting on November 9 and Ogawa and Teranishi on November 10. It was the first ascent of the northwest face. The Japanese route is Grade VI, 1,600m, and 80º.

The Slovenian story

In the autumn of 1989, Bojan Pockar (team leader), Vanja Furlan, and Matjaz Vrtovec targeted Ama Dablam’s northwest face.

On October 12, the trio established a base camp at 4,700m by the Duwo Glacier. The team didn’t place any further camps. Furlan and Pockar climbed in alpine style, starting on October 28, from 4,900m to 6,030m. Their objective was to climb the north face directly, but snow conditions were poor, so they went to the northwest ridge via the north couloir.

The duo climbed 450m of a new route. The route was steep, up to 85º, and they didn’t fix ropes. It took them 17 hours to climb from the bottom of the face to the ridge. In very soft snow covering steep rocks, it was impossible to go higher.

The difficult northwest face of Ama Dablam. Photo: Tomaz Humar

Pockar returns to Ama Dablam

In the spring of 1993, Pockar returned to the mountain, this time with Stefan Mlinaric. Again, he targeted the difficult northwest face.

The two climbers set up base camp at Duwo Glacier. In the early hours of May 2, Pockar and Mlinaric began their ascent of the northwest face from 4,900m. After nine hours of climbing, they managed the “easiest” part of the 2,000m wall, reaching 5,600m. Next, they faced the most difficult section, a steep 400m rock wall. The two climbers expected hard ice. Instead, they found a thin layer of ice, and below that, very soft snow.

Lacking proper gear for the task and not being expert technical climbers, they had to abandon their attempt. They climbed down for two hours through big seracs and were lucky to escape an avalanche. Finally, they made it back to base camp. Their highest point on the northwest face was 5,600m.

The northwest face of Ama Dablam. Photo: Tomaz Humar

Furlan returns

The 1996 Slovenian Ama Dablam Expedition team arrived in the spring. The team comprised Vanja Furlan (leader), Tomaz Humar, Zvonko Pozgaj, and Chindi Sherpa. The Slovenians planned to ascend the northwest face in alpine style.

They set up base camp on April 11 and summited Island Peak to acclimatize. Only Furlan and Humar would climb Ama Dablam.

Humar and Furlan ascend the northwest face. Photo: Tomaz Humar

On April 21, Furlan and Humar made their first attempt. But bad weather arrived and lasted until April 25. Because of heavy snowfall and frequent avalanches, they put their tent under a serac at 5,630m and waited for good weather, which didn’t come. The duo had to retreat to base camp on April 28, taking all their gear down with them. On this first push, they made it to 5,780m.

On April 30, Furlan and Humar started up again. They made a continuous push to the top by a more direct route than that of the 1980 Japanese party. Furlan and Humar summited on May 4.

Pink line: The 1980 Japanese route. Red line: The Stane Belak-Strauf Memorial Route. Photo: Montblanclines

During their impressive ascent, the duo made six bivouacs. The first bivy was on the Japanese autumn base camp route on a serac at 5,630m. The second was to the left of the Japanese route in a hanging bivy. Another bivy involved digging out a ledge from hard ice on the face.

Coming down, they had to bivouac a few more times while descending the southwest ridge route at the top of the Dablam Glacier. The two climbers then descended through a camp set up by a Swedish-American team, before losing their way below Camp 1 in the fog. They spent their sixth bivy not far from the normal Ama Dablam base camp site.

On May 6, they finally reached their base camp.

Homage to Stane Belak

According to Furlan and Humar, both of them in their 20s at the time, the most difficult part of their route was on May 1 and 2. On those days, they ascended from 5,680m to 6,010m. This section was the crux of the ascent, through icy sections of 70º and 90º, with two very difficult pitches (V+, A2+, 1,650m, AI5). You can read a full report by Vanja Furlan for the American Alpine Journal here.

Furlan and Humar named their line the “Stane Belak-Strauf Memorial Route” (1,650m, VI, 5.7 AI5, A2+) in memory of their friend Stane Belak, who died a few months earlier. Belak died on Dec. 24, 1995, on 2,366m Velika Mojstrovka in the Julian Alps.

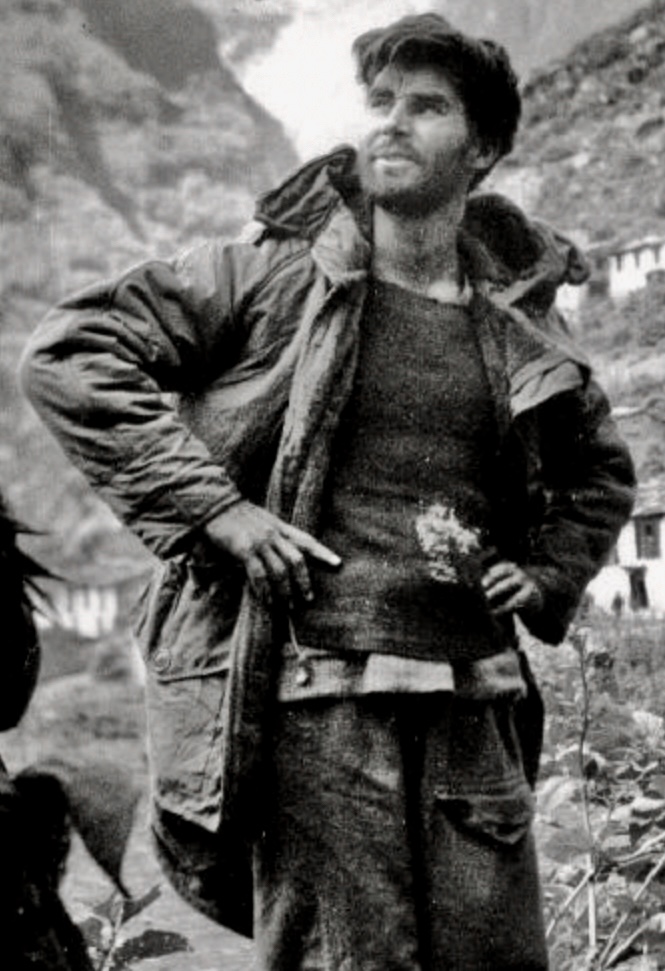

Vanja Furlan during the Ama Dablam expedition. Photo: Tomaz Humar

Just after the Ama Dablam expedition, Furlan turned 30. Three months later, on August 15, 1996, Furlan’s short, intense mountaineering career ended. While climbing the Kovinarska route on the north face of Velika Mojstrovka, he suffered a fatal fall. It was the same mountain where Belak had died the previous year.

“Vanja [Furlan] was a member of a new young generation of Slovenian alpinists who made the step from big expeditions to small ones, to alpine-style and solo climbing in the Himalaya,” Franci Savenc wrote for the American Alpine Journal at the time.