Charles Dubouloz and Simon Welfringer describe themselves as dreamers and adventurers. No wonder they chose to climb somewhere quiet and difficult this season. Yet it’s not far from Everest.

The new route they opened on Hungchi (7,029m) was not their intended goal. Their original objective was the neighboring (and higher) Gyachung Kang (7,952m). “When you go on an expedition to the end of the world, things rarely happen as expected,” Dubouloz explained.

The weather didn’t cooperate, Welfringer fell ill with bronchitis, and their expedition time was quickly running out.

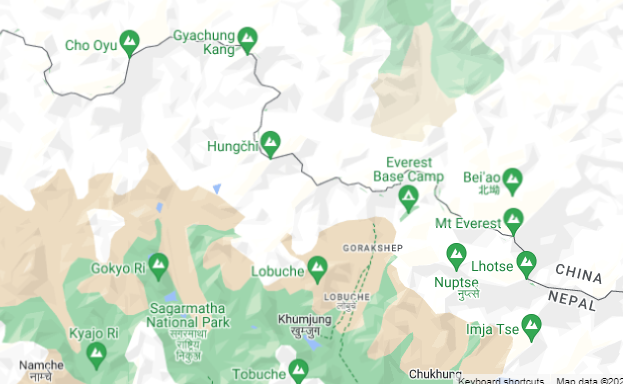

Hungchi’s location on Google Maps. The peak lies between Everest and Cho Oyu.

“[Eventually], our gaze naturally turned towards this stiff and aesthetic face,” Dubouloz wrote, referring to the west face of Hungchi.

Behind the Khumbu

Hungchi is actually not at the end of the world but rather on the border with Tibet, just a short distance from Everest as the crow flies. It’s about midway between Everest and Cho Oyu.

But the climbers are right in one sense: Despite its proximity to the crowded Khumbu, Hungchi is a little-known peak with only three previous ascents: two in 2003 by Japanese and Korean expeditions up the southwest ridge, and a third one from Tibet in 2006 by another Japanese team.

Dubouloz and Welfringer chose to open their line up the virgin west face. Only elite climbers could handle this formidable wall.

Dubouloz and Welfringer in front of Hungchi. Photo: Mathurin-Millet

The team climbed in pure alpine style, with no ropes or previous partial climbs, no depots, and one single push. They started on May 17 from an Advanced Base Camp at 5,300m. At the time, Welfringer had not fully recovered from his bad bout of bronchitis.

The climbers in a couloir on the lower sections of Hungchi. Photo: Mathurin-Millet

Progress was slow, and the pair had to improvise a bivy at 6,580m, Millet (their sponsor) reported in a press release. Somehow, Welfringer overcame his exhaustion, and they pushed to the summit the following day.

One of the climbers on a vertical ice section. Photo: Charles Dubouloz/Millet

On May 18 at 1:30 pm local time, Dubouloz had a special birthday celebration on the summit.

Unfortunately, the descent was nothing to celebrate. Sudden high winds and a whiteout forced them to bivouac again just 300m below the summit.

A difficult decision

An icy bivouac. Photo: Mathurin-Millet

When they awoke on May 19, it was still snowing. They made a crucial decision to abandon their tent to go faster. And they switched to the east face, which they didn’t know, also hoping for a swifter descent.

It was risky because they were unsure they would find a way off the face. Luckily, it worked. After several hours and some dead ends, the climbers ended up on a different side of the mountain, safe and sound.

A stern test

“These three days put our mountaineering skills and motivations to the test,” Dubouloz reflected, but admits that the achievement left them happy and fulfilled.

‘Le cavalier sans tete,’ the new route by Dubouloz and Welfringer up the south face of Hungchi. Photo: Mathurin-Millet

The pair has not yet assigned a grade to their 1,700m route, but they did give it a name: Le cavalier sans tête (The Headless Rider). The name comes from a melodic song by Saez about a headless rider searching for love among the blizzards.