Another piece of the Franklin Expedition puzzle has dropped into place. However, like most new bits of information concerning this enduring exploration mystery, it raises more questions than it answers.

Using samples from a living descendant of an expedition member, researchers from the University of Waterloo and Lakehead University struck upon a DNA match with a mandible found on King William Island, Nunavut. The remains of at least 13 expedition members have been recovered in the area.

“We worked with a good quality sample that allowed us to generate a Y-chromosome profile. We were lucky enough to obtain a match,” Stephen Fratpietro, of Lakehead University’s Paleo-DNA lab, said.

The mandible is from James Fitzjames. Fitzjames stepped in to captain one of the ships after Sir John Franklin, the expedition’s leader, died on June 11, 1847.

Fitzjames’ mandible is one of four sets of remains from the site that show evidence of cannibalism.

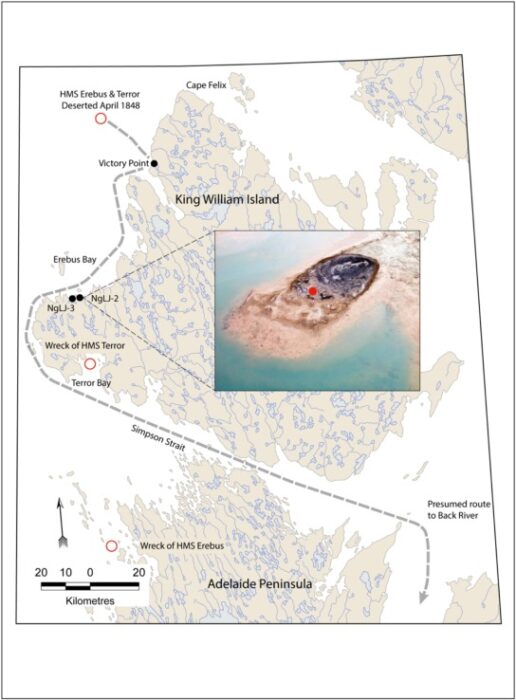

A map of the expedition’s travels and the site where the mandible was discovered. Graphic: Stenton et al

“This shows that he predeceased at least some of the other sailors who perished and that neither rank nor status was the governing principle in the final desperate days of the expedition as they strove to save themselves,” Douglas Stenton, adjunct professor of anthropology at the University of Waterloo, explained.

“Identifying Fitzjames’ remains provides new insights about the expedition’s sad ending,” he continued.

The team published its findings in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

A doomed expedition

The expedition, helmed by seasoned polar explorer John Franklin, set out from Britain in May 1845. Franklin aimed to find the Northwest Passage, a navigable waterway linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Two ships, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror, held 129 men.

After two years with no word, the first of 39 rescue missions was dispatched. Yet Europeans never saw any of the 129 men alive again.

In the subsequent decades, searchers, researchers, and archaeologists have continued to uncover relics, bones, and other evidence of the expedition. A key discovery was the so-called Victory Point Note. Scribbled in the margins of a standard Admiralty form, the note is dated May 28, 1847. It indicates that the men abandoned the Erebus and Terror after the ships became trapped by crushing ice. After leaving the ships, the crew’s goal was to hike south toward the Canadian mainland.

“Sir John Franklin died on June 11, 1847, and the total loss by deaths in the expedition has been to this date nine officers and 15 men…[We] start on tomorrow 26th for Backs Fish River,” the message reads in part. Fitzjames and Franklin’s second-in-command, Captain Francis Crozier, signed the dispatch.

Human remains from the expedition dot the western and northern coasts of King William Island. Fitzjames’ mandible was recovered from a site known as NgLj-2.

A photograph of James Fitzjames’ mandible showing signs of cannibalism. Photo: Stenton et al.

Utilizing traditional knowledge passed on by the area’s Inuit inhabitants, researchers discovered the sunken wrecks of the Erebus in 2014 and the Terror in 2016. Underwater excavations of these sites are ongoing.

Armchair sleuthing

Remembering the Franklin Expedition is a Facebook group roughly 4,000 members strong. The group’s participants range from casual fans drawn by the expedition’s recent portrayals in works of fiction to scientists with decades of Franklin research under their belts. ExplorersWeb previously interviewed Randall Osczevski, a retired Arctic scientist who now spends his days peering at publically available satellite imagery, hoping to find clues behind the lost expeditions’ final days.

And it was another of the group’s members, Fabienne Tetteroo, who helped track down a possible Fitzjames descendant for a DNA match. Tetteroo connected that person with the DNA researchers.

Tetteroo had been conducting independent research on Fitzjames for two years before starting to write a book on him. The book will form part of her master’s degree in Naval History from the University of Portsmouth, England. During her research, she discovered that Stenton and his team were struggling to find any of Fitzjames’ descendants to test for a DNA match.

“The possibility that someone had found Fitzjames’ remains but that this could not be tested was enticing. Through genealogical research, consulting a handwritten family tree, and online birth records, I found an eligible candidate for a match with Fitzjames,” Tetteroo told ExplorersWeb. “Thankfully, this person was happy to participate. I’ve been dreaming of the day that someone would find Fitzjames, and now this dream has come true.”

The timing couldn’t be better — Tetteroo turned in her thesis last Friday.

A community mourns and celebrates

To a group of people who obsess over the discovery of every button, nail, and scrap of leather, the news is cause for both celebration and somber reflection.

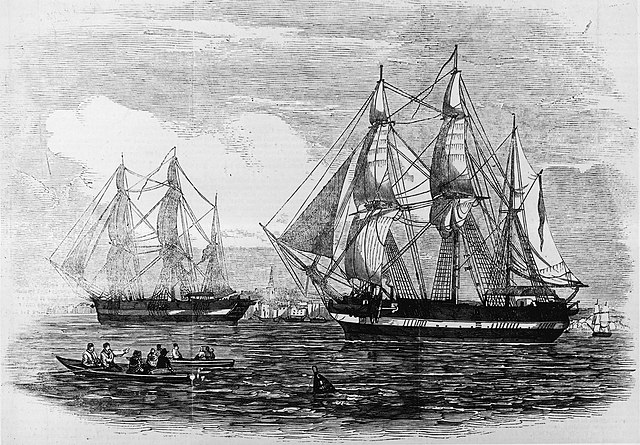

An illustration of the Erebus and Terror as the ships departed England in 1845. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

William Battersby was an institutional marketer who left that career to become a prolific Arctic historian and author of a book on Fitzjames. He passed away in 2016, but his daughter, Maddie Battersby, is a member of the Franklin Facebook group.

“[I feel] relief, disbelief, and grief; for Fitzjames, for the many families with loved ones in the expedition who died not knowing what happened to their loved ones, and for me. I grieve for my dad, who died eight years ago, and so hasn’t lived to see this development,” she said.

“I just wish I could go back in time and tell him that in the future, when he’s found, thousands of strangers will cry for him. Out of sadness…because no one deserves to die like this, but also out of relief,” another group member, Hannah Tackett, noted. “Thousands of people not only remember his name 176 years in the future but celebrate when he’s found again. An entire community built around this expedition…will love and grieve together.”

Helping the cause

The scientists responsible for the DNA match are excited about further research but could use a little help from the general public.

“We are extremely grateful to this family for sharing their history with us and for providing DNA samples. We welcome opportunities to work with other descendants of members of the Franklin expedition to see if their DNA can be used to identify other individuals,” Stenton said.

As archaeological technology improves, more puzzle pieces will fall into place. Whether those pieces will eventually assemble into a complete image is debatable.

But in the spirit of exploration against long odds, that doesn’t stop a diverse group of people from across the globe — scientists and amateur Arctic detectives alike — from trying.