One tomb containing a who’s who of fourth-century Macedonian royalty has been a bone of contention in the archaeological community for decades.

Now a recent report in the Journal of Archaeological Science claims to have resolved the controversy. But has it?

The interdisciplinary team from Greece, Spain, and the U.S. claim that their X-ray analysis proves that the “Great Tumulus” contains the remains of several of Alexander the Great’s relatives — and finally resolves whose burial site is whose.

View this post on Instagram

Behind door number one…

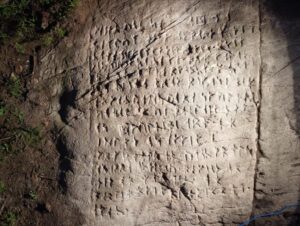

First excavated in the 1970s, the burial site contains three crypts: Tombs I, II, and III. Their occupants are:

- King Philip II (Alexander’s father), his wife Cleopatra (of Macedon, not Egypt), and their newborn child

- King Philip III Arrhidaeus (Alexander’s half-brother) and his wife Adea Eurydice, and

- Alexander IV (Alexander’s son).

Gold funeral wreath of Queen Medea, Philip II’s sixth wife, found in the tomb’s antechamber. Photo: Wiki Commons

ID’ing the remains

It’s a stacked house, and it was richly appointed. But regardless of their pedigree, they’re now just 2,600-year-old human remains. And looters have compromised the site’s integrity to an unknown degree.

Who’s who? It’s never been certain.

Lead study author Antonios Bartsiokas, professor emeritus of anthropology and paleoanthropology at the Democritus University of Thrace in Greece, thinks he’s brought the conjecture to an end. To do it, his team performed X-ray and dissective analysis. They then coordinated the evidence with a historical analysis of the lives of the entombed.

“We studied the skeletal elements with the aid of macrophotography, radiographs [X-ray images], and anatomic dissection,” the study reads. “A knee fusion was found in the male skeleton of Tomb I, consistent with the historic evidence of the lameness of King Philip II.”

Fused knee joint of the skeleton in Tomb I. Photo: Bartsiokas et al

Detective story

Bartsiokas called the work “a fascinating detective’s ancient story” in a LiveScience interview. His team’s work flips the script on the conventional wisdom, which holds that Philip II’s group is in Tomb II, and Arrhidaeus’ is in Tomb I.

Statue of King Philip II of Macedonia in Bitola, Macedonia. Photo: Wiki Commons

(Troubled) lifestyles of the rich and famous: the Argead family

The site is located in the northern Grecian town of Vergina, which was once known as Aegae, the Macedonian capital. That’s where Alexander the Great reigned from 336 to 323 BCE.

For clarity: Every person buried at the Great Tumulus belonged to the Argead family, which ruled Macedon starting in the eighth century BCE. Phillip II guided the kingdom during a relatively tumultuous period from 359 BCE until his assassination in 336. Alexander then took over, increasing the empire’s fortunes notably until he died mysteriously in 323.

Statue of Alexander the Great in Khujand, Tajikistan. After his massive military campaigning, he died mysteriously. His remains’ exact location is still unknown. Photo: Steve Evans via Flickr

Arrhidaeus then took the throne briefly, until his execution in 317. Alexander IV then became King of Macedonia by default — even though he had yet to hit puberty and had mostly lived the life of a war prisoner. Feuding Macedonian generals finally arranged to poison and kill the boy several years after he acceded to the throne. With Alexander IV’s death, the Argead family’s bloodline and associated rule concluded.

The short-lived Alexander IV as an infant with his mother, Roxana. Painting by Alessandro Varotari. Photo: Wiki Commons

Bartsiokas’ team coordinated details from these timelines and life histories with skeletal evidence and burial circumstances to inform the rest of its theories on the Great Tumulus.

Evidence and conflicting theories

They had a man with a bad knee, consistent with Philip II, buried in Tomb I. But what proved the two other bodies with him were Cleopatra and their young child?

Cleopatra was the last of Philip II’s seven wives. She married him young, in the year 337 BCE. But after his assassination, she and her infant daughter, Europa, faced urgent peril. Within a year, they were both dead — along with a speculative infant son, who may have died at the hand of Alexander.

Bartsiokas corroborated this history with growth patterns in the deceased woman’s bones.

Mandibles from Tomb I. The example at right belonged to a young female consistent with Cleopatra of Macedon’s age at the time of her death. Photo: Bartsiokas et al

“This was the only newborn in the Macedonian dynasty to have died shortly after it was born,” he told LiveScience. “The age of the female skeleton at 18 years old was determined based on the epiphyseal lines [which show when the bone stopped growing] of her humerus. [This number] coincides with the age of Cleopatra from the ancient sources.”

Elsewhere in Tomb II, evidence of cremation bears consistency with historic evidence for King Arrhidaeus’ burial, the team stated. Not only that, but the disparity in burial circumstances dovetails with the empire’s improved fortunes between Philip II and Arrhidaeus’ rule.

More clarity but controversy remains

“Tomb I was a very small and poor tomb and Tomb II was very big and rich. This ties in with the historical evidence that Macedonia was in a state of bankruptcy when Alexander started his campaign and was very rich when he died. This is consistent with Tomb I belonging to Philip II and Tomb II belonging to his son Arrhidaeus,” explained Bartsiokas.

That Tomb III belongs to Alexander IV is of little conjecture.

However, conflicting evidence still exists. Philip II famously suffered an eye injury during a battle in Methone in 354. While the skeleton in Tomb I is missing the part of the skull consistent with the injury, the skeleton in Tomb II bears possible evidence of the trauma.

The team’s paper addresses this and other inconsistencies. It blames the malformity in Tomb II on the “warping” of the skeleton during cremation.

Case, or tomb door, closed? It still depends on who you ask.