As the Chinese proverb goes, “When the winds of change blow, some build walls, others build windmills.” In the case of several remote villages in Iran and Afghanistan, this could not be more true. For centuries, these villages have suffered harsh wind storms that sweep down the plains.

Their answer? Odd-looking structures made from clay and wood. They may not look like much, but they house ingenious mechanical designs. These are the world’s oldest windmills, called “asbads.”

Though asbads have slowly been replaced by more advanced designs, some locals strive to maintain them. They are one of the world’s first renewable energy prototypes.

The creator of the first windmill

Abu Lu’lu’a Firuz was a Persian slave who lived in the mid-seventh century AD. He was a non-Muslim and may have originally been a Zoroastrian priest.

Non-Muslims were banned from entering and living in the region’s Rashidun Caliphate, the empire that immediately succeeded the prophet Muhammad. But because of his exceptional engineering skills, Firuz was allowed access to the capital in Medina alongside his master.

Firuz specialized in machines that could harness the wind and attract the caliph’s attention. According to the History of al-Tabari, a chronicle written in 915AD, the caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab said, “I heard you make windmills. Make one for me as well.”

“By God, I will build this windmill of which the world will talk,” Firuz replied.

This seemed like a good set-up for political favor but it did not turn out that way. Umar established a harsh tax which Firuz refused to pay. Firuz then assassinated Umar while the caliph was leading prayers in a mosque. We are not sure what happened to Firuz after.

However, we know that his invention stood the test of time and still functions today. He created a type of windmill referred to as a panemone. This is a windmill with a vertical axis. Only a handful of them still stand.

Harnessing the wind

After taking the Muslim world by storm, windmills made their way to other parts of Asia and Europe in the 12th century. After invading Iran, the Mongols found them so impressive that they sought to kidnap windmill engineers.

Windmills started popping up in China, Africa, and Europe. Inventors modified them into different shapes, sizes, and designs. But it was only centuries later in Northern and Western Europe that windmills started to take on a horizontal axis. Eventually, horizontal-axis windmills became the most widely used design (as they are today).

A panemone windmill possesses a rotating axis positioned at 90° in the direction of the wind, while the wind-catching blades move parallel to the wind. It is a drag-type turbine. Drag refers to an aerodynamic force that acts opposite to an object’s motion through the air. Drag results in less energy and poor efficiency. In Iran and Afghanistan, the panemone windmill is encased in something called an ‘asbad’.

Two story asbads. Photo: Irandestination.com

An asbad is a two-story adobe, mud, or clay structure. They are typically 20m tall and situated on a hill overlooking a village. The ground floor held millstones to grind grain or machinery to pump water. The top story had a long wall with chambers, each chamber contained six or eight wooden sails dressed with cloth or straw on a vertical axle.

The asbad takes the brunt of strong winds, converting them into useful kinetic energy. As the wind blows through the chambers, it rotates the wheels and vanes to kickstart the grinding or pumping processes below. Harnessing the wind could process a bag of over 100kg of wheat.

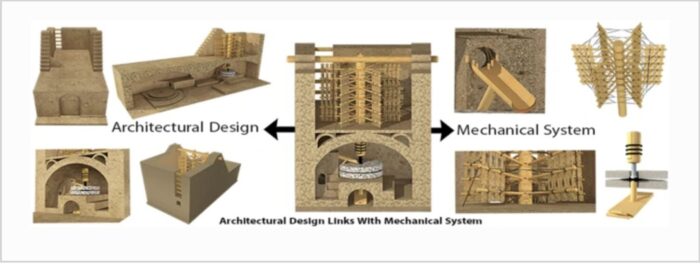

Illustration of asbads and their design. Photo: Heritage Science

The ancient Persians utilized these windmills for two main reasons: to grind wheat and pump water. For the time, asbads were revolutionary and made life much easier. According to historian Robert Forbes, asbads could also chop sugarcane and other crops.

Fighting 120-day winds

The best place to find well-preserved asbads is in the village of Nashtifan in northeastern Iran. Of the 30 windmills there, five are in working order. There are also a few standing in Sistan to the south.

Since the days of the caliphate, the asbads have helped combat the region’s infamous 120-day ‘Sistan Winds’. These wind storms occur from May to September and make life difficult for the villagers. They cause intense droughts and can blow at up to 100kmph. In 1991 these winds carried so much dust along the Iran-Afghanistan border that it dried up Lake Hamun. As a result, nearby villages were abandoned and people had to migrate elsewhere.

Vertical axis windmills in Sistan. Photo: MorvaridiMeraj/Wikipedia Commons

The Sistan Winds result from the interaction between seasonal winds and the landscape. Their intensity gave rise to the village’s name, which translates as “storm’s sting.”

Heritage

While they seem obsolete compared to modern technology, the asbads play a vital role in the lives of Nashtifan villagers. They draw tourists and are a key part of the villagers’ cultural heritage.

In 2002, the Iranian Government recognized the windmills as part of the country’s heritage. Unfortunately, maintenance is quite difficult. In Nashtifan, Mohammed Etebari is on a mission to preserve these ancient prototypes. He meticulously cares and cleans them every day. Let’s hope that someone steps up to look after these historical treasures when he is gone.

While horizontal-axis windmills are still the norm, some see the benefits of vertical-axis turbines. William Walker of Stress Engineering Services believes that vertical windmills are easier to maintain, would work better for farms, can withstand very high winds, and can reduce production costs. They cause less harm to the environment, less noise pollution, and can generate enough electricity for small-scale operations.

So, could these ancient windmills compete with modern wind turbines? According to National Geographic, an asbad could not even power a lightbulb. Whether useful for generating energy or not, it would be a great shame to let these historic windmills disappear forever.