In her new book, author Bernadette McDonald has focused on a group of mountaineers who remained mostly in the shadows until recently: the local climbers who work for high-altitude expeditions.

Thoroughly researched, Alpine Rising: Sherpas, Baltis and the Triumph of Local Climbers in the Greater Ranges fills in some crucial gaps in mountaineering history. The enthusiasm, passion, and genuine care for these men and women is palpable on every page.

The book is a succession of exciting stories of true adventure. It reviews some epic events, from the first ascents of Annapurna and K2 to recent new routes on alpine 6,000’ers and winter triumphs on Nanga Parbat and K2.

The stories are told from the point of view of those local climbers themselves: Ang Tharkay, who carried on his back the barely surviving pioneers of the first ascent of Annapurna; Gyalzen Norbu Sherpa, one of the first to summit Manaslu; Little Karim, who played key roles in so many Karakoram ascents; and Ali Raza Sadpara, winter expert and master of a new generation of Pakistani climbers, to name a few.

It does not avoid the sometimes somber aftermath of expeditions: injured workers left with no insurance or future, widows forced to raise entire families by themselves, or careers destroyed by alcohol.

Masters of their own destinies

The book runs from the so-called conquest of the 8,000’ers during the second half of the 20th century to the current era of social media. It would be easy to stop with denouncing an unfair, colonialist past, but the book is more than that. In those hundred years, local workers have gone from friendly (and expendable) assistants to, at times, celebrity climbers, “successful entrepreneurs and masters of their own destinies,” as Jon Krakauer writes in one of the book’s blurbs.

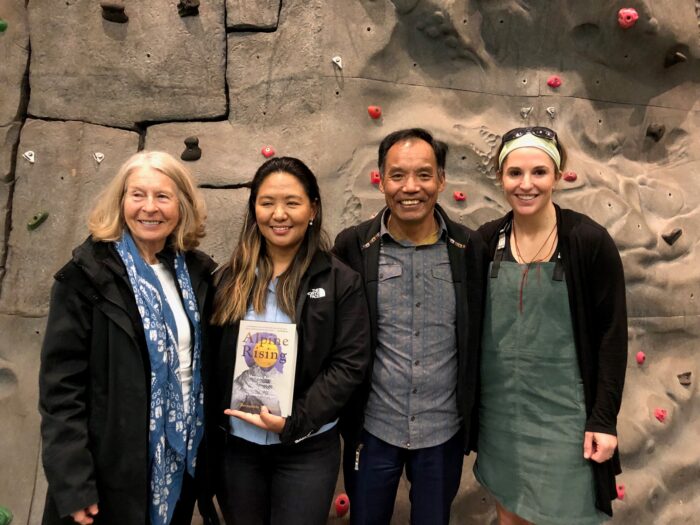

Bernadette McDonald, left, at the book presentation in Seattle, with Dawa Yangzum Sherpa, Lakpa Rita Sherpa, and Melissa Arnot.

For me, as a journalist who knows many of the stories in the book intimately — ExplorersWeb is cited 25 times in the end-of-volume references — perhaps the only things I missed were nuances, or maybe just multiple voices, on some of the stories. I am always astonished at how different stories seem, depending on who tells them.

Subjectivity is unavoidable, especially when witnesses at their physical and mental limits. Also — and this is indeed reported in the book — lack of communication and poor coordination are at the heart of many mountain dramas. Hence the need to gather several incomplete accounts that, taken together, add up to something of a whole.

The bitter brawl between the sherpas on Everest and Simone Moro, Ueli Steck, and John Griffith in 2013, for example, seen from the side of the sherpas, was the logical reaction to intolerable insults. At the same time, videos of the event showed a dangerous level of group violence that is hardly a shining moment for anyone involved.

Broad Peak 2021

Also, the rescue of Nastya Runova on Broad Peak in 2021: The only testimony provided in the book is that of Little Hussain. While accurate and worth noting, it looks incomplete without mentioning other climbers who also helped. And I would have welcomed some context about the drama that was taking place some meters above, with several climbers (both locals and foreign) trapped on the ridge while another stranded climber, Kim Hong-Bin of South Korea, eventually died.

Focus on local voices

At the same time, the author has made a deliberate editorial decision to focus on voices usually ignored. The point is to celebrate the evolution of those who carried much of the weight of the Himalayan expedition history on their backs. So while it would be desirable to hear multiple points of view, that is perhaps a different book.

The oversized Everest Base Camp last year. Photo: Pasang Rinzee Sherpa

On the business side, the fast development of commercial Himalayan expeditions of today has brought some shadows: unsustainable practices in fragile ecosystems, mistreatment of employees by local entrepreneurs, and a predictably passive government response.

It is interesting to note that many of the Nepalese climbers and entrepreneurs who now dominate the expedition market in their country are interviewed for the book, but surprisingly, there is no word from the biggest of all: Tashi, Mingma, and Chhang Dawa Sherpa, the three brothers who run the powerful Seven Summit Treks.

When I interviewed author Bernadette McDonald recently about this latest book, she explained that she tried to contact them through several channels, but none of them was successful. Inside baseball fact: I’ve never managed to speak to them either.

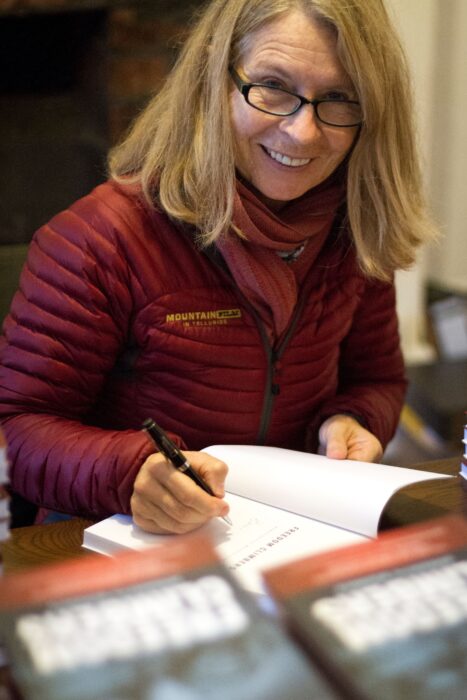

Bernadette McDonald. Photo: Mountaineers Books

Interview with Bernadette McDonald

The idea for the book, said McDonald, came “while I was interviewing Ali Sadpara for the book about winter 8,000’ers. I felt that Ali Sadpara was not getting as much acknowledgment as he should after his part of the first winter Nanga Parbat summit, although it was clear to me, as to other people, that he was the powerhouse on that climb.”

The late Muhammad Ali Sadpara of Pakistan. Photo: Elia Saikaly

McDonald went on: “The question stood in the back of my mind: How could this top, committed climber, and also such a nice guy, not get the credit that he should? He did in Pakistan, but not internationally. [When] Mountaineers Books approached me to write a book about Winter K2, I thought that was, in fact, part of a bigger story and a great chance to give all local climbers, not only on K2, the recognition they deserve.”

The purpose of the book

“My goal,” she said, “was to transmit stories as directly as possible, exactly as the climbers I interviewed said it. These are their stories, that for whatever reasons had not been told before.”

For this purpose, McDonald relied on Sareena Rai in Nepal and Saqlain Muhammad in Pakistan. They had the connections, spoke the local language, and did a great job suggesting names, interviewing, recording, transcribing, and translating.

“The book wouldn’t have been possible without them,” she said.

McDonald noted that part of the writing took place during the COVID lockdown. Then she had to undergo a knee replacement, which was followed by long weeks of immobility.

“It isn’t meant to be a lobbying or activist kind of book as much as a long-range look at the evolution of climbing for local climbers,” she explained. “From the pure labor, following-orders kind of work in the 1930s and onward, all the way through the various changes to the point we are at now. When I was trying to choose which climbs to include (and obviously there are hundreds that I couldn’t include), I was looking for those incremental steps that created a new reality for local climbers.”

The changing Himalayan scene

“The course of history for local climbers has been fascinating, especially in Nepal…The Nepalese have responded swiftly to the requirements of the market, which demanded lots and lots of summits as quickly as possible, and they have become experts in providing those services.

“The Sherpa also provided a service when they were hired in Darjeeling for the pioneering expeditions…but they learned and improved their skills, and their role in the expeditions grew from mere porters to actually leading their Western clients.

“It is something that happened long before the first Nepalese companies were born. I keep coming back to the example of Pasang Dawa Lama, who factually led the Austrians Herbert Tichy and Sepp Joechler to the first summit of Cho Oyu in 1954. Or Pertemba Sherpa on the SW Face of Everest, who played a critical role in the 1975 British expedition.”

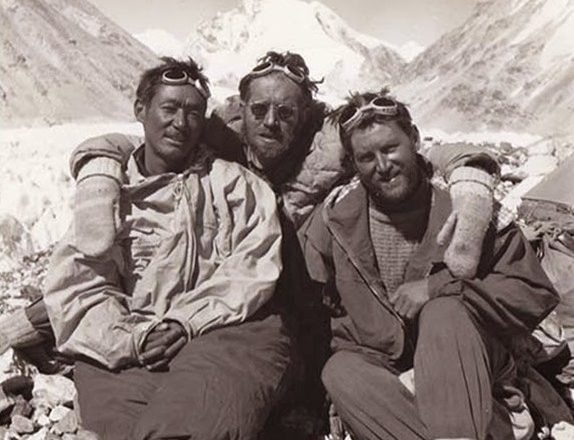

Pasang Dawa Lama, Herbert Tichy and Sepp Joechler. Photo: Desnivel

Education is key

“Improving education also played an important role: If you think of the evolution of climbers from Pakistan and Nepal, the lack of educational opportunities in some areas has clearly held those climbers back, not just in terms of marketing themselves, but in terms of standing up for their rights. The lack of access to proper climbing and rescue training has also hampered their progress.”

The internet, she believes, “was the biggest game changer. When local climbers could begin interacting with the world, tell their own stories, market themselves and their businesses, everything changed.”

Sherpa women on top: Maya Sherpa, Dawa Yangzum Sherpa, and Pasang Lhamu Sherpa Akita on the summit of K2 in 2014. Photo: Al Hancock

Colliding points of view?

What happens when the locals share points of view that differ from the widely accepted version previously given by the Western teams? What about the bitter comments from locals who feel let down by their foreign employers? Such issues are present at some moments of the book.

“Maybe I’m being naive, but I am hoping that respectfully telling these stories will not raise controversy,” McDonald stated. “I tried very hard to give a voice to the actual climbers, and therefore, that voice tells his or her story as directly as possible. I think the reader will need to keep that in mind when making judgments.

“In the end, the key to the interviews I conducted was respect,” she concluded. “That is what local climbers are mostly asking for.”