On May 25, Christian Havrehed and Sun Haibin will start rowing from China to Japan. It is the first step of their journey to find out whether the Chinese made it to America before Columbus. They hope to find the answer by following the clues in two ancient Chinese tales.

The first story tells of Xu Fu, a court sorcerer who lived around 210 BC. It is said that the emperor ordered the sorcerer to find the elixir of life. Xu Fu set off. He returned years later claiming that he had found the elixir, but that the gods of the Eastern Sea required an offering to relinquish it.

With 3,000 men and women as the offering, Xu Fu set off again. He traveled eastward and never returned. Academics believe he must have gone to a place unknown to the emperor. If so, he may have continued east after Japan, potentially landing in America.

The second story starts in 499 AD. Chinese Buddhist priests wrote of a monk who set out across the Pacific Ocean to spread the Buddhist faith. After sailing eastward for months, he arrived at a place they called Fusang.

The book contains multiple descriptions of Fusang, the people there, and where the monk stopped along the way. Although academics have studied the text, no one has ever tried to follow the trail. And that is exactly what Havrehed and Haibin plan to do.

Fusung story: legend or map?

Is it possible that the Fusung story is a map to America? That may sound far-fetched, but Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad found the Viking settlements in Newfoundland similarly, by following the pathway described in the Icelandic Sagas.

This is not the first time Havrehed and Haibin have stepped into a rowing boat together. They rowed the Atlantic together in 2001. In doing so, Haibin became the first Chinese person ever to row an ocean.

Havrehed became the first Dane to row the Atlantic. The main aim of that journey was to promote unity between China and the West. The journey was a huge success, especially in China, where they were front-page news. Haibin was voted Sportsman of the Year.

Now the duo hope to replicate their success of two decades ago. While the main purpose of their journey is to discover if the Chinese made it to America before Columbus, they also hope to strengthen Sino-Western cross-cultural understanding.

ExplorersWeb spoke to Havrehed about the journey.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity

You were supposed to start last May but didn’t get the permit. Now you have it. How difficult was that logistically?

We were asking for something that had never been granted in the history of the People’s Republic of China. They are not open to international yachting, and we are trying to go to Japan. Right now, geopolitically, everything is difficult between China and Japan.

Permit problems

I think we got this permit for several reasons, mainly because we’ve been pestering them for three years. Usually, a government department sponsors such activities, but they all thought the risk was too great. This is something that has never been done before.

Eventually, we told them, “Look, we really want to do this. We have lined everything up, and we’ve been asking for three years. Everybody thinks this is a great project, and we just need permission to leave. We understand we can’t have an official sponsor. But you should still allow us to leave just as adventurers because we are two stupid middle-aged guys with a dream we want to fulfill.”

Of course, we are in a privileged position because normally you wouldn’t have access to some of the bureaucrats we needed to speak to. But when we rowed the Atlantic, it was way off the scale of what was possible in China.

We came back and were heroes in China. Everybody saw this positively. I think because we have that history and just threw all the arguments at them that we succeeded. We did everything they asked us to do. I speak Chinese. I know the history better than most. So in the end, I think that is why they gave us this chance.

The route to Japan. Photo: Christian Havrehed

Shore crew in Japan

Why will you have a safety team following you in Japan?

We have a crew following us on shore in a car to help us at night when we get to ports. It’s not recommended to row the coast or to be on the water at night in Japan because there are a lot of fishing vessels and nets.

The local fisheries association owns all of these small harbors, and it used to be up to them to allow you to enter or not. But that law in Japan changed after the Tokyo Olympics. Now you can get a permit, so you are allowed to use these previously closed ports. But you have to take that with a grain of salt. The law might have changed, but that information may not have made it to these tiny fishing villages.

So we need some people who speak Japanese, who understand the culture, and who can make sure that when we get there we are allowed to use the port. We want to have good interactions with local people because this is all about trying to create understanding.

You’re also running an outreach program in these places?

We’re working with a UK NGO called Atlantic Pacific, whose purpose is to provide lifeboats. Atlantic Pacific also runs summer courses to teach Japanese kids life-saving and environmental preservation in the sea. We hope to send a child from each port we stop in to join the course.

Photo: Christian Havrehed

Search for relics

How much time will you spend at each port?

The coastline is very dramatic. Often it’s just sheer cliffs. You only have a few exit points. We have to be careful with the weather to make sure that we can make it to the next port. We plan to row 50 to 60 kilometers a day and know we might have to wait out bad weather.

Also because it’s all following in the wake of Xu Fu, this ancient magician, we’ll look at relics in two of the ports. We will work with the local caretakers of these relics, then we can tell the story of Xu Fu’s significance to this place.

We had hoped to stop at two further places with relics but we’ve had to cut the row short by about 500 kilometers. The local communities there were not welcoming to the prospect of us coming.

What is your updated route?

We will start in Zhejiang, China and row 800 kilometers to Nagasaki, Japan across the East China Sea. After Nagasaki, we follow the coastline for a further 500km, stopping at the various ports each night.

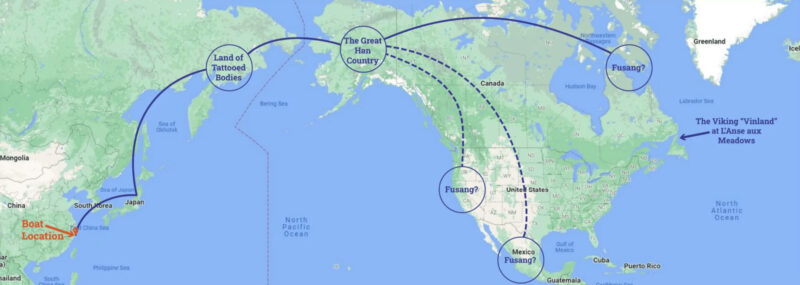

That is the first stage of the expedition. Then, depending on what we find, the route takes us from Japan to Siberia, Siberia to Alaska, and Alaska to Newfoundland.

The full journey. Photo: Christian Havrehed

Earlier attempts

A few people have attempted Xu Fu’s journey but have been unsuccessful. Why do you think this will be different?

Tim Severin tried to imitate Xu Fu’s voyage by going trans-Pacific on a bamboo raft. He left Vietnam because he couldn’t leave mainland China, but his vessel broke up in the Pacific. Then before that, you had a Danish-Austrian team with their best guess of what a junk in 200 BC would have been like. It also broke up in the Pacific.

Academia suggests Xu Fu may have made it to America. But I think if Xu Fu went on from Japan, he wouldn’t have gone trans-Pacific. It is much more likely that he went to Japan, then north to Hokkaido. Then from Hokkaido through the Kuril Islands to the Russian peninsula of Kamchatka. Once you get below the Bering Strait, you have the Aleutian Islands.

That way, you can almost always see the next island in your path. That’s a completely different kettle of fish. Then you can ask on this island: What are the people like on the next island? What should I bring? Is there food, is there water? It’s a much simpler and safer way of getting to America.

But so far, no one has investigated that way of getting to America. [Editor’s note: In 1999-2000, kayaker Jon Turk paddled from Japan to Alaska.] No one has looked to see if they can find archaeological breadcrumbs of Chinese presence along that route to America.

Trail of cookie crumbs

Are you planning to do archaeological work along the route?

This is an old story. It has never been proven. We will try to put the Chinese in America before Columbus by following a trail of archaeological relics. That’s our game. That’s the research purpose. We don’t move forward if we don’t have a reason.

It is not possible to do archaeology in each place. But for each segment of the larger journey, I will first do desktop research. I read all the history books I could find. Then I reach out to all the academics and museums who don’t want to have anything to do with me, but hopefully, they will be more open after this first stage.

Once I have a pearl string of potential places to visit, I visit them by modern means to see, is it bullshit or is there solid evidence? Then if it’s solid, I’m happy. Then we use the human-powered expedition as a form of storytelling. I hope it will make the academic research more interesting to the wider public.

Havrehed and Haibin after their Atlantic row in 2001. Photo: Christian Havrehed

Reluctant scholars

Why don’t academics want anything to do with you?

Because basically, they see me as a charlatan. Some people think I am another Gavin Menzies. He wrote 1421: The Year China Discovered the World. It was a huge success, an international bestseller. He spun a great yarn, but it was so far from historical fact that the academic world got extremely pissed off. They had been doing scientific research for years and years and years, and no one had ever noticed them. So Gavin Menzies ended up doing this subject a huge disservice because now no academic wants to touch this subject with a barge pole.

A few academics say, “Okay, Christian, this is interesting. I’ll support you. You can borrow my research assistant, but don’t mention my name.” I understand their perspective. I appreciate the help and the expertise that they can give me. This taught me the importance of persistence.

Background

You rarely see such an academic research project tied in with ocean rowing. Where did that idea come from?

As a kid, I always loved to read about discovery at sea. I love these stories about going by boat, visiting new places, and exploring. I love the adventure side of this.

I’m an accidental academic but I understand that if this was experimental archaeology, if I made my best guess of what Xu Fu’s vessel would have looked like and tried to sail it trans-Pacific, it wouldn’t prove anything even if I succeeded. It wouldn’t move the discourse.

No one is willing to entertain this idea anymore. The pushback would still be, “Oh, yeah, well, of course, anybody can get lucky. It’s probably nothing like the vessel he used.” The only way we can move it along is to go from one archaeological clue to another.

The idea that the Chinese were in America so early is not new. Until 1830, everybody thought that the Chinese had been in America before Columbus. But then the Opium War happened, and in Europe’s eyes, China went from being a high culture to a low culture. And you can’t have low-culture people inventing or visiting America pre-Columbus. After that, the whole story died down.

The Viking example

Then another Dane said that based on the Icelandic Sagas, it seemed like the Vikings made it to America. Yellow-haired, blue-eyed, nice Scandinavians made it to America pre-Columbus, and everybody went, that’s better. That story was accepted. But then you have from 1830 until 1960, where this is only a hypothesis or a theory, right?

In 1960, the sagas led the Ingstads to Newfoundland. They went ashore and asked the local population if there were any old buildings around. They were shown some Indian ruins, which turned out to be the houses the Vikings had described in the sagas. Here, they followed a story that people had written off as just a story.

L’Anse Aux Meadows, Newfoundland, where the Ingstads discovered the Viking ruins. Above, the replica village near the original site. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Then if you go back to around 1885, you have a German called Heinrich Schliemann. He wanted to find Troy. All the academics said this is mythical. It doesn’t exist.

He found Troy using The Iliad‘s description. So there are two precedents for this. For us, the Fusang story has as many directions as The Iliad and the Icelandic sagas. Hopefully, we’ll be as lucky as Schliemann and Ingstad.

Pierre Paul Ferdinand Mourier, Christian’s great-great-great-great grandfather. Photo: Christian Havrehed

Family ties

This trip also has some family ties for you, doesn’t it?

There are quite a few. My fourth great-grandfather was the Chief of Trade for a Danish trading company with China from 1770 to 1785. While there, he picked up Chinese, which was illegal for foreigners to learn then. But he learned it from a Spanish Augustine monk.

Then he came back to Denmark speaking Chinese. And that’s as useful as having the world’s first video phone. But he’s recognized as Denmark’s first Sinologist, the first academic to study Chinese language and culture seriously. His works are in the National Museum or the National Library, and academic papers have been written about him.

It’s quite funny actually. I told you how in 1830, the story about Fusang was discredited. The guy who discredited the story was a German academic called Julius Klaproth. And guess who taught Julius Klabroth Chinese? So it’s personal.

Then there was my grandfather and great-uncle, both called Christian. My grandfather was in the Navy and went on a diplomatic mission from 1899-1900, where he visited Shanghai. My great-uncle sailed between America and China several times with the U.S. Merchant Marines. So we seem to have a familial interest in seafaring in China.

Ocean rowing experience

You and Haibin rowed the Atlantic in 2001, which was quite a while ago. How much ocean rowing have you both done since then?

I bought the boat that we’re using in the UK in 2020, and I rowed it to Denmark with three UK marines training to row the Atlantic later that year. Then in 2022, because it was the pandemic and we couldn’t do anything in China, I thought rowing around Denmark would be a good challenge. It also let me see what it is like to row coastal in an ocean-rowing boat and to go to shore and do events with the local population. Sun Haibin hasn’t done any ocean rowing since 2001. But I’m not worried. Before rowing the Atlantic, he had never been off dry land.

Short haul across the East China Sea

Is there a section that you’re particularly looking forward to?

I’m very much looking forward to arriving in Nagasaki. The first two or three weeks of life on the ocean are very uncomfortable. Psychologically you have to do a lot of adaptation.

Only after two or three weeks do you start enjoying it. It becomes everyday life and you don’t think you’re going to die all the time. We don’t get into that space because our trip to Japan will be maximum, touch wood, two weeks.

When would you like it to start the second leg of the journey?

I think in two years, simply because I hope we are busy doing the speaker circuit after this trip here so we can start recovering some money and do more research. If these speaking gigs don’t happen, we’ll try to begin by the end of 2024. We’re not getting any younger.

You can follow the journey here.