Animals that evolved in warm, tropical climes rarely decide to move to cold, snowy ones. Take any creature from the African grassland and drop it in Austria during an Ice Age, and the poor creature would surely not fare well.

Except Homo sapiens. We did just that, expanding into some of the coldest regions on Earth. New research into a 24,000-year-old site shows how technological innovations helped early humans keep warm during the Last Glacial Maximum.

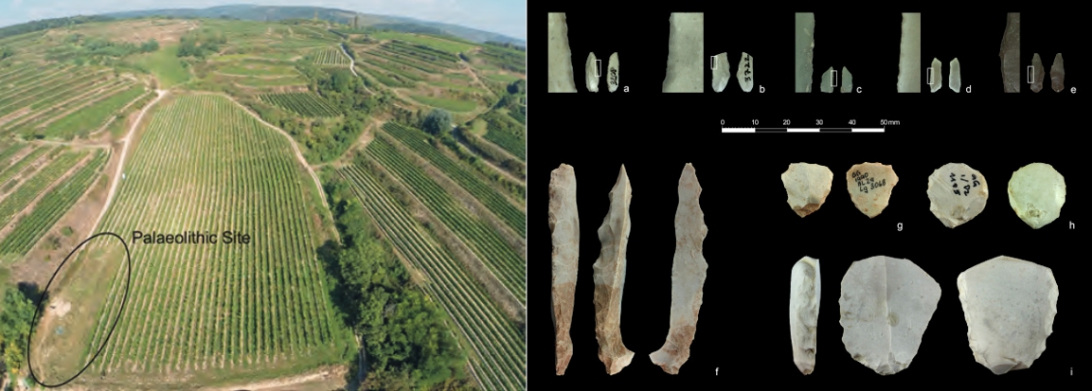

Left, the paleolithic Kammern-Grubgraben site from above. Right, stone tools found at the site. Photo: Einwögerer et al, Handel et al

The early humans of Kammern-Grubgraben

While we tend to associate early humans with caves, Austria’s Kammern-Grubgraben site is open air, with a highland on one side and a sloping river valley on another. Between 20 to 24 thousand years ago, humans frequently lived there.

Nearby sites had an even older human history — 33,000 years. They were hunter-gatherers, who moved with the seasons, returning to the same camps year after year. Sophisticated tool users, they produced a wide range of stone tools, as well as jewelry.

The Kammern-Grubgraben site also contains a wealth of organic remains. Those remains belong almost entirely to one species: Rangifer tarandus, the caribou, or reindeer.

The people of Kammern-Grubgraben hunted caribou almost exclusively during the winter. Researchers knew the hunts had taken place in winter because the skulls still had their antlers, and reindeer shed their antlers after winter. Tooth wear also indicated winter or late autumn deaths.

Why were they only hunting caribou during the winter and autumn? Researchers believe that it was for their hides.

Reindeer bones, teeth and jaws recovered from Kammern-Grubgraben. Photo: Pasda et al

Sewing for survival

As the Thule people in the Arctic discovered much later, caribou hide makes clothing warm enough for almost any conditions. Their thick pelts of hollow, air-trapping hairs conserve heat like nothing else. Once the people of Kammern-Grubgraben acquired these hides, they used sophisticated sewing tools and techniques to create cold-resistant clothing. Sewing traditional fur clothing requires incredible patience and skill, but it can also be incredibly effective. Recreations of Stone-Age clothing handled even in harsh Northern winters.

In the same chronological layer as the caribou bones, archaeologists found eyed bone needles. Eyed needle technology allowed them to sew tight, fitted seams, making clothing much warmer and sturdier than simple draped pelts.

Around 24,000 years ago, the Last Glacial Maximum caused temperatures to plummet. In nearby sites that dated from before this Ice Age, archaeologists found a much broader range of animal remains, and no eyed needles. Here, the most commonly hunted animal was the mammoth, suggesting that hunters prioritized calories over clothing.

When their environment changed, the Stone Age people adopted new lifestyles and techniques to suit their new, chillier environment. This superior winter clothing allowed them to survive an increasingly harsh and unstable climate.