Despite what proponents of pseudo-archaeology would have you believe, the past is interesting enough without bringing aliens into it.

For instance, there are plenty of history-altering, world-shaking figures whose burial places are unknown. And we’re not talking about quasi-mythological figures from the Bronze Age like Agamemnon or Odysseus. Proven historical figures like Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and Cleopatra are all resting in places unknown.

In some cases, these lost tombs result from cultural practices. Other times, the mystery springs from secrecy, betrayal, intrigue, or a combination of all three.

The quest to find the bodies of these figures is as fascinating as the history of how they came to be lost in the first place. What spectacular funerary goods lay in Cleopatra’s tomb? What could we learn from Genghis Khan’s DNA? And what insights might a hypothetical set of Alexander the Great’s journals hold?

So plop on your pith helmet and settle in. Lost tombs await.

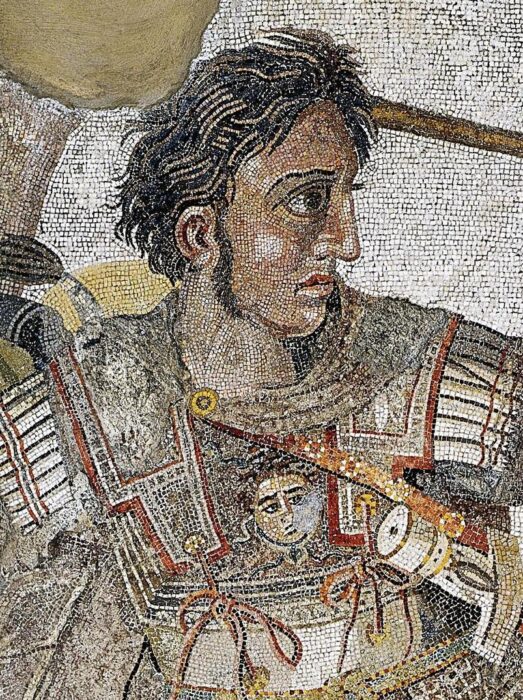

Alexander the Great

There’s a reason they call him “The Great.” Alexander of Macedon was one of the most audacious, skilled, and well-traveled humans the world has ever known. By the time Alexander was 20, his father, Phillip II, had accomplished what no one else had ever managed — uniting the eternally battling city-states of Greece under military rule.

Phillip II didn’t stop there. Bolstered by deadly Greek hoplites (heavy infantry), the Macedonian army was moments away from invading the deadly Persian Empire when he was assassinated.

Alexander the Great changed the course of human history during his short life. After his death, his body was stolen and taken to Egypt. And that was just the start. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Alexander inherited his father’s army and promptly took up where his father left off, eventually doing what no one in the classical world thought possible — toppling the Persian Empire. Alexander then continued toward the edge of the map, eventually turning around on the Indian subcontinent after his exhausted troops threatened to mutiny. Along the way, he spread Hellenistic (Greek-like) culture across the Near East and Central Asia, an act historians agree altered the course of human history.

Alexander returned to Babylon to rule his new empire. But it wasn’t to be. Shortly before his death, someone asked him who should inherit the empire. His answer, famously, was “the strongest.”

Doomed empire

It was a sentiment typical of the brusque young warrior, but it ultimately doomed his hard-won empire. His closest generals almost immediately fell into civil war, eventually dividing up the spoils among themselves. Ptolemy, perhaps the most gifted of them, ended up in Egypt, making his seat in the Alexander-founded city of Alexandria.

Meanwhile, a caravan containing Alexander’s body was on its way back to Macedon. In a move seemingly custom-designed to irritate his former comrades, Ptolemy had it snatched and brought to Egypt.

The corpse, initially enclosed in a form-fitting coffin of hammered gold, eventually wound up on display in Alexandria. Over the centuries, luminaries from antiquity, like Julius Caesar, Augustus, and Cleopatra (more on her later), made pilgrimages to honor Alexander’s legacy and ponder their own. By the time Caesar saw it, Alexander’s body was resting in a spectacular coffin with a see-through crystal top.

An engraving by Sebastien Bourdon shows the artist’s imagining of Roman Emperor Augustus visiting the tomb of Alexander the Great in Alexandria. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It’s unclear when or how the tomb was eventually lost. In the centuries between the rise and decline of the Roman Empire, various historical figures looted the tomb for gold or relics. So it’s possible a well-meaning leader secreted away the body to stop the practice. In any case, when the early Christian John Chrysostom visited Alexandria in 400 AD, no one remembered where Alexander the Great lay buried.

Excitement and disappointment

Given how often we know Alexander’s body changed hands, moved, or was looted over the centuries, it’s unlikely that the tomb, wherever it is, contains the wonderous treasures that delight museumgoers. But it doesn’t matter. Archaeologists have been searching for it since before archaeology was an official branch of academia.

And so the hunt was on. The Egyptian Supreme Council for Antiquities cataloged over 140 official attempts to find the body, and there have doubtless been many under-the-radar quests as well.

Initial 19th-century consensus placed the tomb somewhere within Alexandria. The problem is that Alexandria has been continuously occupied since its founding in 331 BC.. It has thus endured all the earthquakes, fires, civil unrest, sackings, and religious changes you’d expect.

Alexander’s tomb might have been paved over or buried during an earthquake. It might be under a Christian church or a mosque, and the people who run each aren’t generally too happy to see workers with shovels and pick-axes showing up on the doorstep.

A drawing of Alexandria by Magdalena van de Pasee shows the famous lighthouse with the city in the background. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Enter Heinrich Schliemann

Everyone’s favorite bumbling-yet-brilliant early archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann, had a pet theory and petitioned a mosque to excavate but was denied. Given the lasting damage Schliemann did to Troy — and his tendency to assume whatever he stumbled upon was what he was looking for — that’s probably a good thing.

In more modern times, archaeologists have expanded their search beyond the borders of Alexander’s most famous city. Some Greek archaeologists have proposed that Alexander’s body, not his father Phillip II’s, is buried in Macedon.

Others claim that relics found in the Siwa Oasis — an important location in Egyptian spirituality and Alexander’s conquest of Egypt — hold his remains. As recently as 2021, Egyptian officials claimed to have found evidence of Alexander’s tomb there, though the tomb itself never materialized.

One National Geographic television host claimed that the body was stolen by merchants and taken to Venice, where it is now venerated as the body of Saint Mark the Evangelist. This possibility seems the least likely, though given the remains’ long history of being snatched and used for personal gain, who can say?

And so the hunt for the body of Alexander the Great continues.

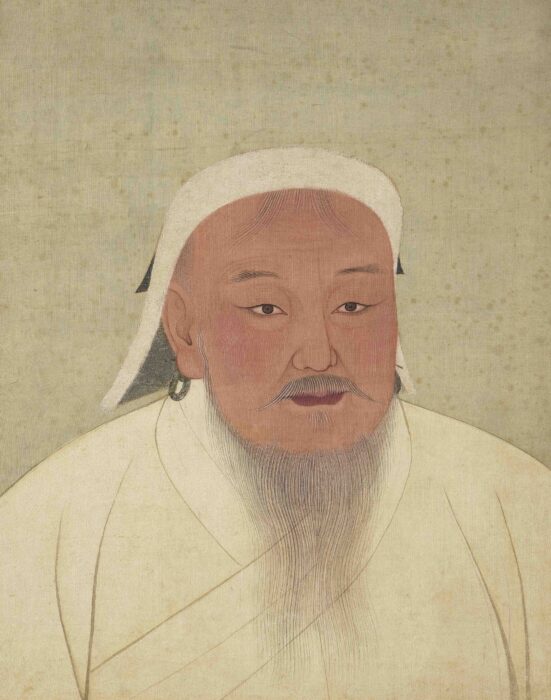

Genghis Khan requests a humble burial

We’ll return to Egypt, that land of oh-so-many lost tombs, in a moment. But first, a brief side trip across Asia to examine one of history’s other great lost conquerors, Genghis Khan.

Dubbed Temujin after his birth on the Asian steppes between 1155 and 1167 AD, the fierce warrior consolidated his fractious people and set to work. Horse archers are some of history’s most implacable battlefield opponents, and the Mongols, under Genghis Khan and his descendants, eventually created an empire that stretched from China to Eastern Europe. The utter devastation the Mongols wrecked on the powerful Islamic empire, in particular, allowed Christian Europeans to get a toehold in the Holy Lands — another historic inflection point that still has powerful ramifications in modern geopolitics.

A portrait of Genghis Khan later in his life. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

When he died in August 1227, he was buried in a spot he’d chosen earlier, on or near a mountain called Burkhan Khaldun, close to his birthplace. However, Genghis Khan’s successors immediately kept the funeral details secret, probably to prevent rival court factions from interfering with the body.

On top of that, Genghis Khan reportedly requested no grave marker at his burial place. Only a small honor guard knew the exact location of the body, and the mountain and surrounding regions were promptly declared taboo.

A sacred mountain

As with the corpse of Alexander the Great, time and political upheaval took their toll. The Mongol Empire eventually fractured and decayed, and those who knew the burial location died without passing on their secrets. Folklore developed over the centuries holds that a river was diverted over the burial place to further hide it, or that trees were planted over it.

Due to the political unrest in Asia over the last century or so, serious searches for Genghis Khan’s tomb didn’t really ramp up until the last twenty years or so. Most of the questing has been done remotely and non-invasively with satellites or drones.

For instance, in 2015, Dr. Albert Yu-Min Lin used publicly available satellite imagery and crowd-sourcing to identify 55 possible burial sites. He published his findings in the journal Public Library of Science One, but the sites have yet to be excavated.

Burkhan Khaldun, a sacred Mongolian site long-rumored as the final resting place of Genghis Khan. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Archaeologist Pierre-Henri Giscard and scientific image specialist Raphael Hautefort unearthed another promising lead at around the same time. The two men led a team that used drones to image the top of Burkhan Khaldun and uncovered a tumulus — a heap of earth and stone piled over a burial site. The scientists claim that the 250m-long mound is of human origin and modeled after contemporaneous imperial Chinese burial mounds.

Unfortunately, Giscard and Hautefort conducted their expedition without permits — they didn’t even let local authorities know they were in the area. Genghis Khan is, quite understandably, a figure of some national pride for Mongolians, and Burkhan Khaldun is still considered sacred by local populations. To date, the tumulus is still unexplored — just like Genghis Khan would have wanted.

Things end badly for Cleopatra

Cleopatra is often relegated to a footnote in the story of Rome’s troubled transition from a republican to an authoritarian government — or dismissed as a classical sex symbol who slept her way into power. But she deserves better from history.

By all accounts brilliant, she was a skilled linguist who was the first member of the Greek-speaking Ptolemaic dynasty to learn Egyptian. She was also a masterful politician. With a little help from Rome, she successfully fended off a coup attempt by her younger brother. In short, she was shaping up to be one of the most capable leaders Egypt had seen in years.

However, the Roman civil war eventually spelled the end for both Egyptian autonomy and Cleopatra herself. In the wake of Caesar’s assassination, rival factions coalesced around Octavian (later Augustus) and Mark Antony for control of Rome. Choosing between humiliating client-state treatment at the hands of Octavian and possible joint rule with her lover Antony, Cleopatra made an understandable, if fateful, choice.

Her last-ditch naval effort at the Battle of Actium ended in defeat for Cleopatra and Antony. The two retreated with what was left of their army to mainland Egypt to await invasion by Octavian’s forces. As the wolves closed in, the two elected to kill themselves rather than fall into the invader’s hands.

A bust of Cleopatra. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Buried together

Octavian, displaying the political tact that would soon mark him as among the most skilled of Rome’s mixed bag of Emperors, allowed the two to be buried together without defiling their corpses. (It should be noted that the Roman historian Plutarch claims Antony was cremated, but sources are mixed.)

But Octavian was also nothing if not pragmatic. As an Egyptian leader from the powerful and wealthy Ptolemaic dynasty, Cleopatra’s tomb was completed long before her death, and many people knew where it was at first. Octavian certainly did — he made sure to loot it of the vast treasures Cleopatra had stashed away there.

According to Roman sources, he used the gold, silks, and jewels to pay off debts, to further consolidate his power, and to bribe his troops into not sacking Alexandria. The circumstances do raise an intriguing historical question — what would the months following Octavian’s final rise to power have been like without that crucial influx of wealth at just the right moment?

Egyptologists disagree

The lost tomb of Antony and Cleopatra shares much with Alexander’s tomb — namely, proximity to the bustling city of Alexandria and nearly two thousand years of human history to sort through. All the difficulties of finding Alexander’s tomb also apply to Cleopatra’s, with the added difficulty that Cleopatra’s life story didn’t inspire the same kind of feverish dedication in 19th-century archaeologists that Alexander’s did.

Still, modern research is promising. Egyptologist Kathleen Martinez has been hard at work on the search since 2005. She is focusing on the Taposiris Magna, a temple to Osiris lying west of Alexandria. Using traditional archaeological techniques as well as ground-penetrating radar, Martinez and her team have uncovered ten mummies from 27 tombs in the area, as well as promising coins and carvings bearing Cleopatra’s image.

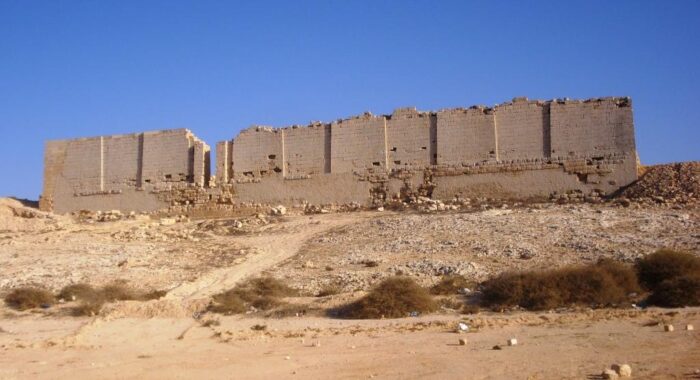

The ruins of Taposiris Magna, where some researchers believe Cleopatra and Mark Antony are buried. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In November 2022, Martinez discovered a 1,300m tunnel under Taposiris Magna, which she believes might lead to the tomb. Excavations are ongoing.

Another prominent Egyptologist, Zahi Hawass, disagrees. At an archaeological conference, Hawass stated that Cleopatra was unlikely to be buried near a temple, as Egyptian temples were for worship, not burial.

The legacy of death

Regardless of this scholarly disagreement, of the three lost tombs mentioned here, that of Cleopatra seems the most likely to be discovered in our lifetime. All we non-archaeologists can do is watch the news.

In any case, if the millennia-long search for certain lost tombs tells us anything, it’s that for those who swing the pendulum of human history, the end is often only the beginning.