The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD destroyed the Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum and is one of the most culturally important volcanic events in history. The rediscovery of the incredibly well-preserved remains in the late 18th century sparked renewed interest in classical antiquity. It has shaped fashion, art, architecture, and popular culture and has inspired paintings, poems, blockbuster films, and songs.

The eerily preserved bodies are part of what made the catastrophe so famous. But that was not Vesuvius’ first major eruption. A new find of fleeing footprints preserved in stone shows another unsettling — and far older — record of devastation.

This 1777 painting by Pierre-Jacques Volaire depicts a Vesuvius eruption in all its apocalyptic glory. Photo: The Art Institute of Chicago

Pipeline work

The discovery only occurred because a gas pipeline near Naples needed updates. In an area so rich in history, any digging requires archaeologists. So researchers and the various companies worked together to preserve what the construction might uncover.

It uncovered a great deal, it turns out. Two years of work on the pipeline have generated an impressive list of discoveries. These include burials from Late Antiquity, votive ceramics from the second and third centuries BC, and a network of ancient roads. It is clear that the area was continuously used over a long period. A Roman villa had at one point been converted into a cemetery, with what researchers believe was an underground martyrium, a buried shrine for Christian martyrs.

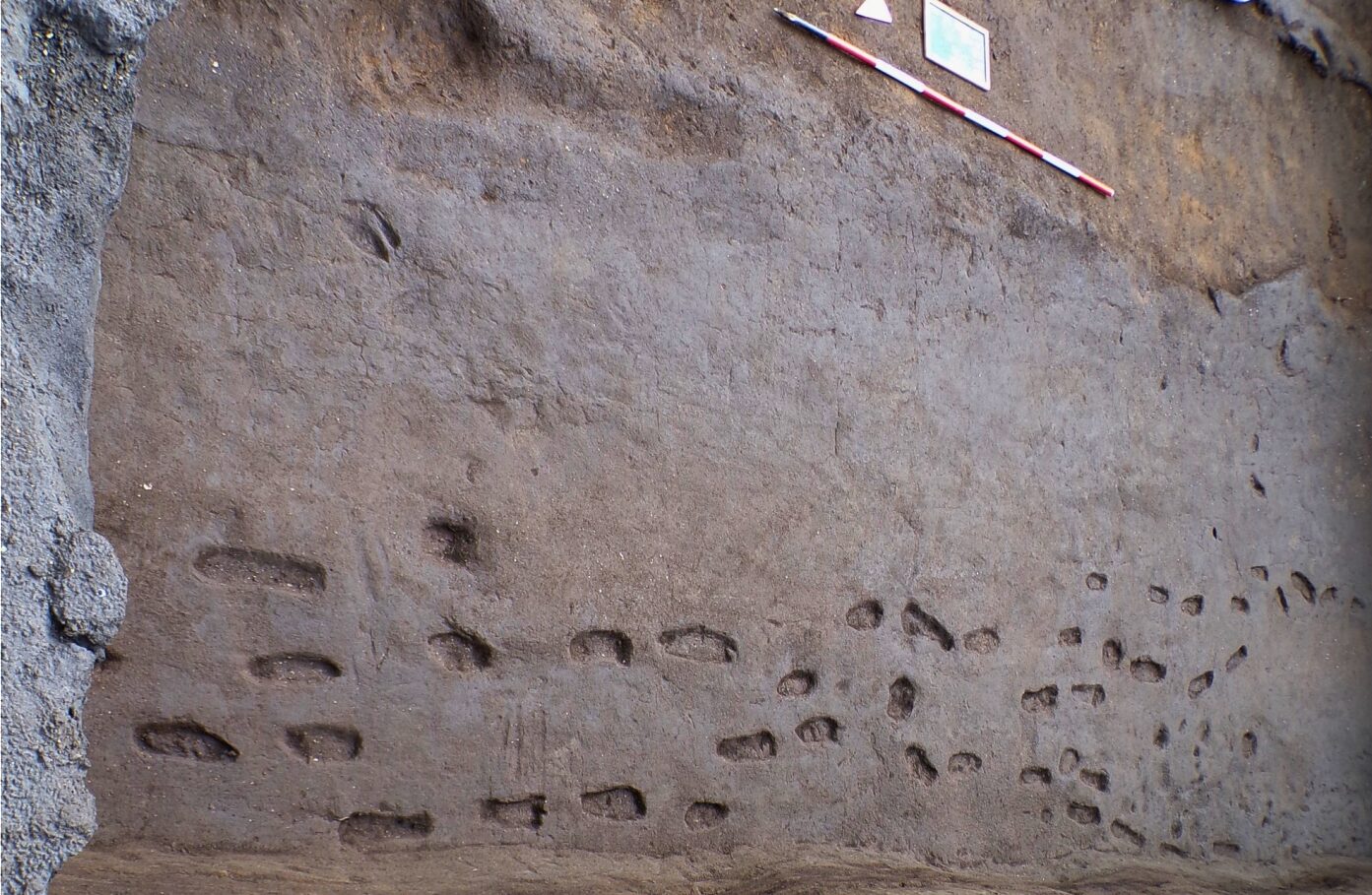

The most dramatic find, however, has to be the footprints. Beside a small stream, dozens of tracks from humans and animals are pressed into the stone.

This sarcophagus, made of volcanic tuff, lies in a cemetery built over an older Roman structure. Photo: Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Salerno e Avellino

Ancient disaster

Before the Christian cemetery, the Roman villa, and the Hellenic sanctuary, there was a settlement of Bronze Age people. They lived along the banks of a stream called the Casarzano, in the shadow of Vesuvius.

Archaeologists know the footprints were made by people fleeing an eruption because they were preserved in pyroclastic deposits. This is the material ejected from a volcano, like cinders, ash, and chunks of rock and crystal, that blanket the earth during an eruption. Panicked people and their animals fled along the stream, attempting to reach a safe distance, leaving their prints in these deposits.

The densely packed footprints give the impression of a frantic, disorganized flight. Photo: Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Salerno e Avellino

We don’t know whether the people who made those prints survived, but we do know that people returned to the area. Pipeline excavations have also unearthed the remains of a Bronze Age settlement that continued to be inhabited into the early Iron Age.