In Nepal, there are 86 peaks (including sub-peaks) between 7,000m and 7,999m, some of which haven’t been climbed for years. Today, we examine the climbing history of 7,893m Himalchuli.

Himalchuli

Himalchuli is the 18th-highest mountain in the world. It lies south of Manaslu in the Nepalese Himalaya and has three summits — 7,893m Himalchuli East (the main summit), 7,540m Himalchuli West, and 7,371m Himalchuli North.

The prominence of the peak is 1,633m, although one side rises 7,000 vertical meters over the Marsyangdi River. It is a huge, steep mountain, and the name reflects this. Meaning “sharp snow peak,” it has seen very few ascents.

The Marsyangdi River, a glacial river in central Nepal. Photo: Solundir

Despite this, Himalchuli’s climbing history is outstanding because of the difficulty of its routes.

Bill Tilman and Jimmy Roberts scouted the mountain in 1950 from the southwest, and other climbers explored the area during the 1950s.

Himalchuli in the middle, Himalchuli West on the left, and Baudha Peak (6,672m) on the right. Photo: Mountains of Travel Photos

The first attempt

Among these early explorers, two young British climbers arrived in the spring of 1953. Their expedition has largely been forgotten. The few sources that mention it typically write it off as little more than a reconnaissance. On the contrary, Herbert Maddock and Harry Hilton’s expedition was an important early attempt.

Maddock and Hilton arrived in Kathmandu from India in early May 1953. On May 23, they left for the mountains, accompanied by five porters. Their main objective was to approach Himalchuli via Buri Gandaki and Chuling Khola. They would then scout a possible route to the summit, and if possible, climb it.

After the attempt, they planned to return down Chuling Khola and Buri Gandaki, then travel east to the sacred lake at Gosainkund, before reaching Kathmandu via the Trisuli River.

However, their plans immediately hit a snag. Hilton fell sick before leaving Kathmandu, so he stayed behind with two porters. Maddock and the three other porters started the expedition, and Hilton planned to rejoin them later.

A view of the Buri Gandaki River valley with Birendra Lake and Samagaon village. Photo: Anton Jankovoy

Couldn’t proceed above 5,800m

On June 3, Maddock and the porters reached Chuling Khola. From there, they targeted the east ridge of Himalchuli. Maddock and porter Garumph ascended to 5,791m (this figure is higher than the one listed in The Himalayan Database, but is correct according to Hilton’s report) before they had to retreat because of insufficient manpower and equipment.

Soon after, the monsoon arrived, and the rivers swelled. Low on money and supplies, they aborted the rest of their plans and decided to return via the Trisuli River.

Between June 19 and 20, Maddock and the three porters crossed a 3,456m pass and camped somewhere before Khading. This marks the last information recorded in Maddock’s journal. What happened next remains a mystery.

According to the porters, and against their advice, Maddock wanted to swim across a wild stream. Maddock subsequently disappeared. According to this version, the porters searched for Maddock for a week but couldn’t find him and returned to Kathmandu.

Hilton’s theory

According to Hilton, Maddock could have been killed after stumbling across a camp of CIA-trained guerillas.

“Mr. Hilton said his attempts to investigate have come up against a wall of silence from American, British, and Nepalese authorities. Documents relating to Mr. Maddock’s disappearance are missing, [Hilton] claimed,” Elizabeth Hawley wrote in her expedition report for The Himalayan Database.

Hilton stated that at the very beginning of the expedition, he saved Maddock from drowning when he fell into a river. That incident “made a vivid impression on Bert [Maddock]. I doubt if he would have taken any chances again,” Hilton wrote.

According to Hilton, Maddock might have run into some tribesmen and Tibetans from the frontier zone who were being trained by the Americans. “If Bert [Maddock] had unwillingly wandered into a guerilla training area or camp, would he have been permitted to leave Nepal?”

The ill-fated 1955 attempt

In the spring of 1955, a British party from Kenya attempted to climb Himalchuli from the southwest side. The six-man team, under the joint leadership of J.W. Howard and Arthur Firmin, was accompanied by Ang Nyima Sherpa and three other porters.

On May 5, the team reached base camp at 4,875m. But they weren’t lucky with the weather and had problems with the porters, too. As a result, they could only make a brief reconnaissance climb to 6,100m. During this ascent, Firmin fell into a crevasse and broke his femur. Firmin died before he reached the hospital in Pokhara.

Japanese attempts

Three years later, in the autumn of 1958, a Japanese team approached from the northeast. The team consisted of Ichiro Kanesaka, Shojiro Ishizaka, Gyaltsen Norbu, Lhakpa Tenzing Sherpa, and Pasang Temba Sherpa. They made it to a steep slope at 6,250m before aborting.

When Japanese alpinists get hold of an idea, they are very persistent. “Every Japanese climber who has been to the Nepalese Himalaya knows and appreciates the steep and distinguished summit [of Himalchuli],” Japanese climber Junjiro Muraki wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

The Himalchuli group from Mani Pass. Photo: Dennis Woodland

Inspired by a Japanese team’s success on Manaslu in 1956 (the first ascent of the peak, and it was to the real summit), the Japanese Alpine Club sent an eight-man team to Himalchuli in the spring of 1959.

Under the leadership of Junjiro Muraki, the team wanted to attempt the northeast ridge.

Muraki’s team started to ascend but found that from the shoulder of Rami Peak, they had to descend a 300m ice cliff to a snowfield above the Chhuling Khola Glacier to reach the summit pyramid of Himalchuli.

“As we were about to fix the route down this cliff, we noticed that Nima Tenzing Sherpa looked exhausted, so we sent him down to Camp 2 (at 5,790m) for a rest, accompanied by a team member and a Sherpa,” Muraki recalled.

But during the emergency descent, Nima Tenzing’s condition worsened. He died at Camp 2 from hemoptysis on the evening of May 4, despite access to bottled oxygen. The next day, the climbers buried him in a crevasse near Camp 2.

Despite the tragedy, the party continued their expedition.

As they ascended, they battled poor weather, snowstorms, and a steep 60°, 1,000m ice wall. Because of limited fuel and exhaustion, they abandoned the attempt at 7,400m.

First ascent

A Japanese team on a 1959 exploratory expedition to Dhaulagiri II examined Himalchuli from the west side. They saw a feasible route from there to the summit.

In the spring of 1960, the Keio University Himalayan Expedition team chose the southwest side for their attempt, based on this new information.

On April 19, Jiro Yamada’s team established base camp at 4,200m, on the big spur issuing from a so-called “sickle ridge.”

On May 1, they established Camp 2 at 5,760m. Two days later, while the team was split between Camp 1 and Camp 2, an avalanche from the upper glacier hit Camp 1. Porter Kazi died and was buried in a crevasse above the camp. Another porter, Pasang Sonum, had to be carried down to base camp on an improvised stretcher made from a ladder. He was sent to a hospital in Pokhara.

Himalchuli during the last ascent of the mountain, by a Ukrainian team in 2007. Photo: mountain.ru

The team continued with their ascent, and on May 23, they put up Camp 6 at 7,300m on the broad snow col between the main peak and the west peak. The climbers started to suffer from altitude headaches and used their 1L per minute oxygen cylinders. Hisashi Tanabe and Masahiro Harada increased their oxygen flow to 2L per minute and subsequently climbed for six hours without stopping. They reached a rock wall beneath the summit.

After this fairly easy rock wall, a very steep ice wall greeted them. The pair cut steps on the wall, traversing to the south. After two more difficult hours, they eventually arrived at the long, horizontal snow ridge that forms the summit of Himalchuli.

On May 24 at 1:10 pm, they arrived at the summit. There, they put up the Nepalese, Japanese, and Keio University flags in a strong wind. A cameraman recorded the moment. The next day, Hideki Miyashita and Kimimasa Nakazawa also summited with bottled oxygen.

Other notable ascents

After that first ascent in 1960, 17 more climbers summited Himalchuli’s main peak until 1986. They climbed by the south face-southwest ridge (1978); the southwest ridge (1984); the southeast ridge-southeast face (1985); again by the southwest ridge (another party in 1985); and by the south ridge-southwest face (1986).

Several attempts from the northeast side of the mountain failed. During this period, for every successful ascent of Himalchuli, there were at least two failed climbs.

The successful 1978 ascent saw three Japanese climbers summit Himalchuli East by the south face without bottled oxygen.

From the northeast

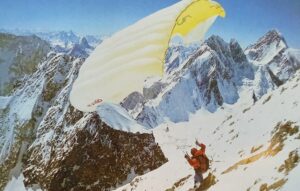

In the spring of 2007, a Ukrainian team led by Mstislav Gorbenko targeted Himalchuli’s main peak via the northeast face-northwest ridge route. They climbed the 21km route without bottled oxygen and six climbers topped out on May 19. This marked the first ascent of Himalchuli from the northeast.

According to The Himalayan Database, 7,893m Himalchuli East has a total of 27 ascents, 18 of them without the use of bottled oxygen. This peak was last ascended in May 2007. There have been no attempts since.

Toward the summit of Himalchuli in 2007. Photo: mountain.ru

Himalchuli West

There have only been five expeditions to 7,540m Himalchuli West, all of them between 1978 and 1990. Japanese climbers Yoshio Ogata and Kazuhiro Sugeno made the first ascent on May 7, 1978, via the southwest ridge.

A total of seven people have climbed Himalchuli West, all without supplemental oxygen. Its last ascent was 33 years ago.

Himalchuli North

The lowest subpeak of the mountain, 7,371m Himalchuli North is similar to the western subpeak, with only seven ascents, all of them in the same year. Its first ascent was via the north face on October 27, 1985, by five members of a South Korean-Nepalese party.

Five days later, on November 1, two Polish climbers topped out via the southwest ridge-southwest face-east ridge route.

There was another attempt in the autumn of 1986 by a German-Italian party via the southwest ridge, but they had to give up on October 15 at 6,500m. Three of the four-man team disappeared. They were possibly hit by an avalanche.

The three climbers, Wolfgang Weinzierl, Guenther Eisendle, and Peter Wauer had no walkie-talkies when they disappeared. The fourth member of the team, Siegfried Reiter, was ill and did not ascend that day. There has not been an attempt on the peak since.