“The summit was not reached,” concludes a thorough report by 8000ers.com. It seems that Grace Tseng and her Sherpa guides mistook the way and stopped 130m away and 50m below Kangchenjunga’s highest point.

They are not the first to make that mistake, Eberhard Jurgalski’s team goes on. The findings come shortly after the controversy over Tseng’s Manaslu. It has not been a good end to the year for the Taiwanese climber.

In the broader picture, this also emphasizes how double-edged certain mountain achievements are, especially those trumpeted as “history-making” on social media.

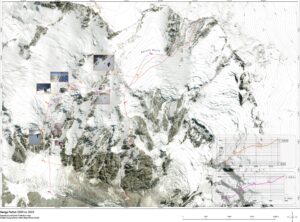

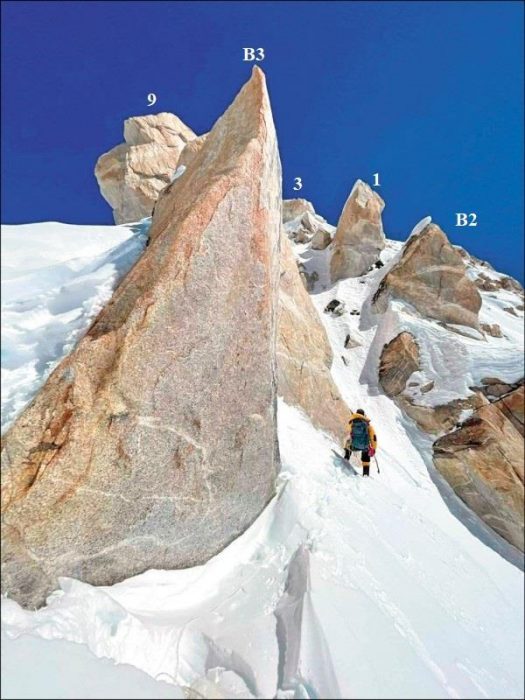

Tseng’s team probably missed the route around the upper block and went left to the so-called Pinnacles (numbered subpeaks) instead of right to the summit. Compiled by Rodolphe Popier of 8000ers.com on a picture by Ferran Latorre. (Mur Difícil means difficult wall in Catalan).

Climbers on Kangchenguna’s upper slopes. The Pinnacles, left, and physical features (two shelves on the way to the top) are marked, as well as the west (W) side of the main summit. Photo: Samuli Mansikka

Summit pics are not summit pics

ExplorersWeb and Mozgasvilag.hu highlighted the issue earlier this week. Like the 8000ers.com team, KrisAnnapurna and Laszlo Pinter, writing for the Hungarian publication Mozgasvilag.hu, based their research on geographical references from Tseng’s summit imagery. We checked with Grace Tseng, her lead guide Gelje Sherpa, and the climbers who followed the ropes laid by Tseng’s team the following spring. Our joint conclusion agrees with 8000ers.com’s statement:

The Sherpa team guiding Grace Tseng almost certainly went the wrong way into the Pinnacles and stopped at a point far below the main summit of Kangchenjunga…Their published ‘summit’ photos do not match any known images of the summit and do not include any of the views of surrounding peaks that would verify their location. Their images do, however, show views that are only experienced lower on the route, [and] which are not visible from the summit.

Looking toward Jannu and Yalung Kang from Kangchenunga’s summit. Photo: Boyan Petrov, via 8000ers.com

In Grace Tseng’s ‘summit’ video, nearby peaks are located differently from where they should be from the summit. Frame from Tseng’s video via 8000ers.com

“The highest climbing pictures are mostly taken at the western edge of the Pinnacles area, then within the Pinnacles area itself,” the 8000ers.com report continues. It concludes that the group exited from the normal classic traverse to the Pinnacles area instead.

A member of Grace Tseng’s team approaches the Pinnacles, each marked by 8000ers.com. Photo: Grace Tseng’s team

A member of Mingma G’s team on Kangchenjunga in April 2022, following Tseng’s white rope to the Pinnacles. Some of Mingma G’s team reached the end of the ropes and saw that they were in the wrong location. They retreated and climbed to the true summit again on a different day.

As usual, 8000ers.com shares a highly detailed, thorough study of graphic evidence from Tseng, her team, and many other Kangchenjunga climbers. Both the complete report and the summarized PDF version are freely available through the links above.

No functioning tracker

On her expedition, Grace Tseng relied completely on her Sherpas: leader Gelje Sherpa, Nima Gyalzen Sherpa (with whom she has climbed all her 8,000’ers), plus supporting staff Dakipa Sherpa and Pasang Rinzee Sherpa. Tseng told ExplorersWeb that she had no InReach on Kangchenjunga, so no tracking points are available.

However, when journalist Laszlo Pinter ask her the same question some days earlier, Tseng replied that she did have tracking files, but she “cannot disclose them because they contain private information”.

As far we could discern, at least one person on that summit push did have a tracker: Gelje Sherpa. He is currently on Cho Oyu’s south side and only intermittently available, but Gelje briefly wrote to us about that Kangchenjunga summit day.

“I had a tracker but it went off at 8,300m because the battery was dead, but I didn’t notice at the time,” he said. “[On the way up] we followed the instructions Dawa [Chhang Dawa Sherpa, CEO of Seven Summit Treks] gave us over satellite phone.”

Chhang Dawa Sherpa had indeed climbed Kangchenjunga before but was not on the mountain at the time. He could hardly guide the team without actually seeing where they were.

Slow pace

We also asked Gelje Sherpa whether the point reached with Tseng was the same place he went to months later when he summited with Adriana Brownlee.

“I do not know if it’s the same point because the weather was bad,” he said, perhaps misremembering. In fact, the weather was excellent on both days, although during that spring 2021 ascent, Gelje and Brownlee climbed in the dark, reaching the summit at 4.30 am. He would not have had an opportunity to compare routes.

Gelje Sherpa near the Pinnacles on Kangchenjunga, Oct 16, 2021.

Gelje on Kangchenjunga’s actual summit, May 2022. Photo: Gelje Sherpa/Instagram

Grace Tseng’s summit push from Camp 4 was excruciatingly slow. According to Pasang Rinzee, they needed over 20 hours to reach the top and seven more hours to return to Camp 4, which is usually 7,600m.

As we pointed out last week, the climbers who followed Tseng’s white rope months later ended up at the Pinnacles. Here, Tseng stopped, according to 8000ers.com. Chris Warner, one of those who later followed that white rope, shared a picture that showed where the rope ended and the summit clearly visible above and to the right.

This is where the white rope ended according to Chris Warner, who reached that place in May 2022. Kangchenjunga’s summit is visible beyond the big boulder, to the right, and above. Photo: Chris Warner

Memories of 2009

Grace Tseng’s controversy recalls the 2009 expedition of Oh Eun-Sun of South Korea. Her claim to be the first female to summit the 14×8,000’ers was rejected after a thorough investigation, led by ExplorersWeb. We concluded that she had not reached the main summit of Kangchenjunga. Her summit picture (below) showed a different background and more snow than other summit pics by other climbers who were on the mountain at the same time. 8000ers.com team has marked the “upper block” below the Pinnacles area, at her feet.

Oh Eun-Sun on Kangchenjunga’s ‘summit’ (actually the Pinnacles area) in 2009. Photo: Black Yak, with the upper block feature labeled by 8000ers.com

Back then, 8000ers.com supported ExplorersWeb’s conclusions, and Miss Elizabeth Hawley of The Himalayan Database marked Miss Oh’s Kangchenjunga summit as “disputed”. She suggested that Miss Oh return to the mountain and summit again to remove all doubts. While Oh always maintained she had summited Kangchenjunga, the worldwide climbing community credited Edurne Pasaban of Spain as the first woman to complete all 14 8,000m peaks.

Equally, Grace Tseng should return to Kangchenjunga, in order to set her record straight on that peak. Unfortunately for her, even this might not be enough to restore her credibility.

Under scrutiny

Grace Tseng climbs have been under scrutiny for the last two years. After Kangchenjunga, the relatively inexperienced Tseng, always climbing as a single client and with a strong Sherpa team, showed up on winter K2 ready to become the first to repeat the 2021 Nepali feat. She eventually retreated, but only after (reportedly) remaining in Camp 4 for several days.

Then she hopped from one 8,000’er to the next, aiming to climb them all as fast as possible. She claimed to have used no O2 on K2 and then the Gasherbrums. Most of her summit pictures are heavily filtered, with no physical references.

Yet it was her Manaslu climb, alone on the mountain with three Sherpas after dangerous avalanche conditions prompted all the other teams to abort, which focused attention on her claims. She returned to announce that she had made it from Base Camp to summit in 13 hours without O2, but so few believed this claim that the company hosting her crowdfunding blocked her account.

Since then, several journalists — including this writer — have been researching and asking Tseng and her support team for details. We studied her GPS tracks and checked all available images. Most have abandoned the investigation because there seems to be no evidence that either proves or disproves Tseng’s claims conclusively.

Nima Gyalzen Sherpa and Grace Tseng on Lhotse. Photo: Facebook

This new controversy around Kangchenjunga has further damaged her credibility, especially in her home country. In Taiwan, the debate has become particularly vitriolic, with supporters and critics staking out strong positions. Unfortunately for her, many of the critics are fellow climbers.

“The record Grace Tseng is trying claim is nearly beyond human capacity, yet we are only left with materials/evidence that could be manipulated, such as her GPS [track],” fellow 8,000m climber Fish Tri told ExplorersWeb. “Metaphorically speaking, it is as if Tseng was claiming that she can fly, and we were trying working hard to find the evidence to prove that humans can’t actually fly, and therefore Tseng’s claims must be wrong.”

Summit proof and meaningless records

In the end, these controversies extend to the contemporary high-altitude climbing scene, where heavily supported commercial clients are quick to claim “world records”.

Claiming a speed record after climbing with the help of three Sherpas makes no sense. Classifying an ascent as no-O2 when surrounded by a support crew sipping oxygen (and carrying spare supplies for you in case you need it) is likewise dubious. In fact, climbing the normal routes on the 8,000m peaks, with well-packed trails and plenty of support (Sherpas, supplies, tons of gear, etc.) has lost the historic value it used to enjoy in mountaineering. It remains a personal pursuit.

Another summit photo shared by Grace Tseng. Photo: Grace Tseng

This trend seems to be here to stay. In a couple of months, we will see climbers or professed climbers announcing plans to do the first something on some mountain. For those still hoping to publicize mountaineering records, here are some tips to avoid the headaches that Tseng has experienced.

- Carry a tracking device and publicly share the ascent live, especially during the summit push.

- Be clear about methods and objectives, after the climb but also before. If you intend to set an FKT or other record, announce it before you begin.

- Take plenty of summit pictures and video footage. Include geographical references and available metadata. Share at least some of it unedited, as proof.

- Ideally, make sure other climbers (besides paid staff) are on the mountain as witnesses.

- Cheating is easy. Technology offers endless possibilities, from editing GPS tracks to creating images with AI. Most importantly, there is no jury to officially validate a climb. In the end, success or failure is a squishy business based on a long-term conclusion from the general mountaineering community. Summit certificates are nice to hang on a wall but prove nothing. Before trying to snag 15 minutes of fame based on what may be a false or exaggerated claim, decide if it is really worth it. Because the speed of social media celebrity works both ways: Negative notoriety comes just as quickly and can be hell, as Tseng has discovered. This has happened even with remarkable climbers such as Tomo Cesen and Ueli Steck. No doubt, it will happen again.