Yesterday Briton Preet Chandi triumphantly announced on social media that she had “broken the world record for the longest, solo, unsupported, unassisted polar expedition by a woman.” That all sounds rather impressive to the uninitiated, and of course, skiing solo for over 1,400km in Antarctica is not inconsequential. But any regular follower of Antarctic travel experiences a sense of déjà vu at yet another hairsplitting record claim.

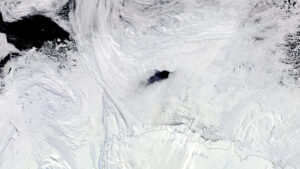

Perishing cold, incalculable remoteness, plunging crevasses, and interminable winds — Antarctica has a fearsome reputation for the lay public. Yet hundreds of scientists spend the year there without incident. The South Pole fell to one of the very first expeditions to attempt it over 100 years ago. And let’s not forget the small number of climbers, skiers, and sledders who successfully (and almost always uneventfully) complete expeditions in various corners of the continent.

Marginal claims – there’s a long tradition

Of these Antarctic adventurers, every year a disproportionate number return with a laundry list of claims. Given that most major firsts (e.g. first person to ski to the South Pole solo, first person to cross Antarctica) have already been bagged, adventurers in Antarctica have long manipulated language and used subtle qualifiers to present their expeditions in the most flattering terms.

This is all part of the game to gain media attention, satisfy sponsors, and increase a social media following. Bankrolling any expedition in Antarctica involves big bucks, and not everyone just withdraws the six-figure sum from his or her bank account.

The most infamous recent example of manipulated language is American adventurer Colin O’Brady’s controversial 2018 solo ski crossing of Antarctica. As a result of O’Brady’s inflated and inaccurate claims, senior leaders in the polar community came together to create a new system for describing and comparing expeditions — the Polar Expedition Classification Scheme (PECS). And while the launch of PECS has forced polar travelers to take more care in describing their journeys, some of this season’s Antarctic incumbents show that spin remains very much alive.

Colin O’Brady at the South Pole in 2018. Photo: Colin O’Brady

A contrived Antarctic record

Preet Chandi, for example, had set out to ski from Hercules Inlet to the Reedy Glacier on the Ross Ice Shelf, a journey of some 1,700km and 75 days. Chandi struggled to keep up with the required mileage in the soft snow and sastrugi. But after 57 days, she eventually reached the South Pole on January 10.

Once at the Pole, Chandi announced that she would keep sledding onward until January 22 and then be evacuated by plane. Only yesterday did it become apparent why the British adventurer had not stopped at the Pole, despite having no time to reach the Ross Ice Shelf. She wanted to claim that “world record for the longest, solo, unsupported, unassisted polar expedition by a woman.” The record was hurried out by her social media team while she was still skiing.

Note that the PECS system does not recognize the term “unassisted.” PECS defines this as “a word used previously to describe a journey that did not use wind energy, dogs, or machines for propulsion.” But given that new journeys should categorize their mode of travel (e.g. ski, snow kite, etc.) anyway, it’s a superfluous term nowadays, simply used to inflate an expedition’s purported credentials.

Photo: Preet Chandi

In any case, the plaudits on social media and major news outlets for Chandi’s record claim have come rolling in. Even the Prince and Princess of Wales seem to have got in on the act.

Poke around a little, though, and you might begin to feel that this is a little contrived. The previous record holder, Anja Blacha of Germany, had set the distance of 1,381km over 57 days on a complete journey from Berkner Island to the Pole in 2019-2020. In addition, Blacha had no intention of setting a distance record.

Media reports place Chandi as having skied 51km (1,397km over 68 days) further than Blacha and having taken 10 additional days to do so. Those extra kilometers came as part of an incomplete expedition, and as a presumably conscious decision to go that little further simply to craft a record. Considered in that context, it doesn’t quite have the same punch.

German adventurer Anja Blacha. Photo: Anja Blacha

Record or not, skiing 1,400Km alone stands by itself

The acid test of the veracity of Chandi’s “unsupported” claim will require clarity on whether Chandi skied on the South Pole Overland Traverse (SPOT) road, a graded, marked road from the South Pole toward the coast. Chandi’s tracker does appear to show her skiing near it, although the Reedy route and SPOT road are close together for the first few days out of the Pole. In addition to this, it is now well-accepted in the polar community that a record is not official until verified by PECS.

The British polar adventurer’s remarkable achievement of skiing 1,397km solo in Antarctica should stand by itself. Does it really need to be spun to make what was an incomplete expedition sound more noteworthy? Does a marginal improvement on a previous distance warrant trumpeting it as a major accomplishment? And can you claim a record by going further than earlier record holders, who didn’t know they were setting/intending to set a record in the first place?

Note that many potential record claims are provided to adventurers by ALE, the logistics company that organizes most expeditions on the continent. They are in the business of selling their wares. Sometimes that means tantalizing adventurers by pointing out how distinct their expeditions are from others. In Blacha’s certification letter in 2020, ALE listed no more than seven potential records, including “the first woman under 30 to ski solo, unsupported, & unassisted to the South Pole.”

Changing the goalposts

The other popular spin tactic in Antarctica is altering the original expedition aims to present a journey in a more favorable light. Gareth Andrews and Richard Stephenson had originally planned a “110 day 2,600km coast-to-coast transect of the Antarctic continent” in 2022/23, a journey that they had grandiosely billed as “The Last Great First”.

However, at some point in the months leading up to the expedition, this changed to “the longest ever unsupported ski crossing of Antarctica (2,023km) and the first unsupported ski crossing of Antarctica by an Australian or a New Zealander.” The duo’s intention was to ski from Berkner Island to the Reedy Glacier in 75 days.

However like Chandi, Andrews and Stephenson found themselves behind schedule, and after 66 days and 1,400km, they reached the Pole on January 18. Here they stopped, thus abandoning their original intention of an unsupported ski crossing of Antarctica. Take a look at the expedition website and Instagram page, however: The journey is now labeled as an unsupported Berkner Island to South Pole expedition.

This change of goalposts only creates more confusion for the media and the public. This is a common spin by Antarctic adventurers.

Andrews and Stephenson at the Pole. Photo: Gareth Andrews and Richard Stephenson

Catapulted by a record

The potential boost to reputation and sponsorship that an Antarctic record brings is too much to resist for nearly all of the current generation of Antarctic adventurers. In most cases, records become a springboard to a lucrative speaking career, a book deal, or product endorsements.

Caroline Cote carried out perhaps this year’s most impressive expedition, by competently breaking the women’s solo speed record from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole by around five days. Note, interestingly, that Cote did not seem to struggle as much as others in the challenging snow conditions. Cote is now represented by a PR agency, which will no doubt leverage the media attention to pull in public speaking gigs, or perhaps to write a book.

But how many formulaic first-person narratives of Antarctic skier versus the great white continent must we endure? What else is left to say? Likewise, there are now hundreds of polar inspirational/motivational speakers. Preet Chandi is doing a great job at inspiring people from underrepresented groups into adventure, but do the many others have such a unique message or story to tell?

Why does it matter?

It should be clear from these examples that Antarctic adventurers strain to sound unique. Every year, another raft of hopefuls repeats the same well-trodden few journeys. When Anja Blacha reached the South Pole in January 2020, she was the 9th woman and 37th person to ski solo and unsupported to the South Pole. Even crossing attempts are now becoming popular, and more are planned for 2023/24.

Consequently, an expedition narrative alone is not compelling enough for the media, for sponsors, and ‘For the Gram‘ anymore. As these many Antarctic adventurers jostle for the limelight, the richness of the experience, the landscape, and the challenge itself become secondary to the need to claim a “record.” In the process, other worthy journeys slip from attention. As we reported yesterday, polar veteran Eric Philips skied an entirely new route to the South Pole this season.

Antarctic adventuring has already begun to earn a reputation that any claim goes. Eventually, the endless spin and arbitrarily defined “firsts” and “records” will wear thin for even the most ardent lover of Antarctic travel. Real, world-class accomplishments remain to be done in Antarctica, including a solo and unsupported full ski crossing of the continent. The get-famous-quick adventurers intuitively realize that this is beyond them. But when the day comes that a fit and hyper-competent traveler takes this on and succeeds, will anyone even care?