Throughout history, the world’s mountain ranges have provided refuge for outlaws. Mountain passes, hidden caves, and steep cliffs allowed these figures to ambush travelers, evade authorities, and launch raids before vanishing into the terrain. Many began as ordinary people driven by poverty, injustice, or war into a life of crime.

Unlike the largely fictional Robin Hood, the outlaws whose stories we’ll tell today were real men who lived and died by the gun and the blade. Some of them became folk heroes and carved legends that are still remembered today in popular culture. This week, we revisit the stories of some of those legendary bad guys who chose mountains to hide from the authorities. Today: the fierce bandits of China and Tibet.

The Heishan bandits of ancient China

During the collapse of the Eastern Han Dynasty (c. 185–205 CE), the Taihang Mountains became the stronghold of a formidable confederacy known as the Heishan (Black Mountain) bandits.

We aren’t just talking about a few small gangs here. This was a massive social movement, a million strong, including families and specialized warriors. In northern China, they were a power you couldn’t ignore.

Their most famous leader, Zhang Yan (originally Chu Yan), was legendary for his physical prowess. They called him “Flying Swallow,” which was a fitting name for someone who could move through those treacherous peaks with such terrifying speed and agility.

These weren’t your typical border raiders. They were right in the thick of the era’s civil wars. They allied with various warlords and frequently harassed the borders of powerful rivals. Because they were too numerous to easily defeat in their mountain fastnesses, the court eventually gave up trying to beat them and tried to buy peace instead, handing Zhang Yan the title of Commandant just to keep things quiet.

Heishan bandits. Photo: The Historian’s Den/Facebook

By 204–205 CE, as the warlord Cao Cao consolidated control over northern China, he recognized that Zhang Yan’s influence was too great to ignore. Rather than attempting a costly campaign to hunt them down, Cao Cao accepted Zhang Yan’s surrender.

In exchange for his loyalty, Cao Cao appointed Zhang Yan as the “General Who Pacifies the North” and bestowed on him the title of marquis. Thus, he successfully integrated the once-lawless Flying Swallow and his followers into the new administration.

China’s Water Margin rebels

Around Mount Liang in northern China, a legendary band of outlaws was active during the Song Dynasty in the early 12th century.

Prompted by corruption, famine, and injustice, ordinary men and a few women fled to the fortified mountain stronghold surrounded by vast marshes. From narrow passes and hidden paths, they launched raids on officials and wealthy merchants. Their code emphasized loyalty and righteousness, earning them a Robin Hood-like reputation.

They weren’t just active around Mount Liang, but also moved across several provinces, including Shandong, Hebei, and Henan.

Known as the 108 Stars of Destiny, and led by Song Jiang (c.1119–1121), they were immortalized in one of China’s great novels, Water Margin. Although the novel blends fact with fiction, existing historical records confirm that Song Jiang was real.

While the novel features the 108 Stars of Destiny, Song Jiang’s band was significantly smaller. Historical records typically cite a core group of 36 leaders, not 108. They eventually surrendered to the imperial court.

To this day, their story remains important in Chinese literature and folklore, symbolizing resistance against tyranny.

A stone statue of Song Jiang at Hengdian World Studios. Photo: Wikiwand

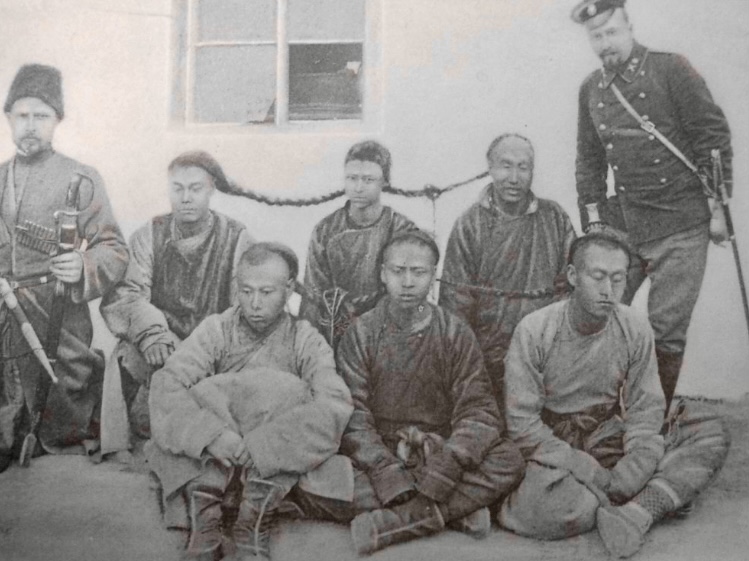

The Red Beards of Manchuria

In the rugged mountains of Manchuria in northeast China, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Honghuzi outlaws (Red Beards) roamed freely.

The term Honghuzi (Red Beards) likely originated from Chinese descriptions of Russian settlers or Cossacks in the 1600s who had red beards. Later, the Chinese bandits adopted the name and sometimes even used fake red beards as disguises.

Many of them started as hunters, deserters, or displaced farmers. They turned to robbery, smuggling, and kidnapping amid foreign invasions and weak central rule. They ambushed caravans, raided villages, and clashed with Russian and Japanese forces during occupations.

Their rapid escapes and guerrilla tactics made them hard to catch, and their legend grew through stories of chivalry mixed with brutality. Some Honghuzi became high-ranking military leaders. For example, Zhang Zuolin, the Old Marshal who ruled Manchuria in the 1920s, began his career as a Honghuzi leader.

By the 1930s, police and modern armies had eliminated many of the last bands. The remainder disappeared after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the subsequent brutal bandit suppression campaigns launched by the Japanese puppet state, Manchukuo.

The Honghuzi endure in tales as wild anti-heroes of the northern frontiers.

Manchurian Honghuzi under arrest. Photo: China-Eastern Railway

Khampas of the Himalaya

You don’t often hear about the Himalaya having its own brand of outlaw, but the Khampas of eastern Tibet were exactly that. (We previously mentioned them in our Gaurishankar story.)

To an outsider, they were just wild mountain bandits, expert with both rifles and horses. They were untamed and quick to violence. To the Chinese, they were bandits and terrorists, but to Tibetans, they were “Buddha’s warriors,” defending faith and freedom. When Chinese forces invaded Tibet in the 1950s, the Khampas resisted fiercely.

Historians often distinguish between their pre-1950s local tribal skirmishes and their post-1956 status as a nationalist volunteer army fighting a formal occupation. By 1956, the valleys in the Kham region swarmed with small, mobile guerrilla units. They ambushed convoys from hidden camps and shared spoils with villagers who fed them information.

A man named Andrugtsang Gompo Tashi managed to pull these splintered groups together under one name: Chushi Gangdruk (”Four Rivers, Six Ranges”), referring to Kham’s geography. Gompo Tashi organized several fights and even helped protect the Dalai Lama’s escape to India in 1959.

Eventually, the CIA got involved, providing weapons and a back-door base in the remote Mustang region of Nepal. Their cross-border raids evaded Chinese units thanks to terrain that only locals could navigate. Operations continued into the 1970s and ended only when U.S. support dried up, and Nepalese forces disarmed the last holdouts in 1974. Wangdu, their leader in those final days, died in a shootout rather than surrender.

Khampa warriors. Photo: Photokunst.com