The Earth: a ringed planet, much like Saturn, surrounded by a hula hoop of asteroids. The summit of Mount Everest: a tropical, vibrant paradise replete with frolicking shellfish and warm waters encouraging plentiful life.

At least, that’s how it was 465 million years ago in the middle of a period in Earth’s history called the Ordovician. Then, the rocks that now make up the top of Everest sat at the bottom of a shallow sea.

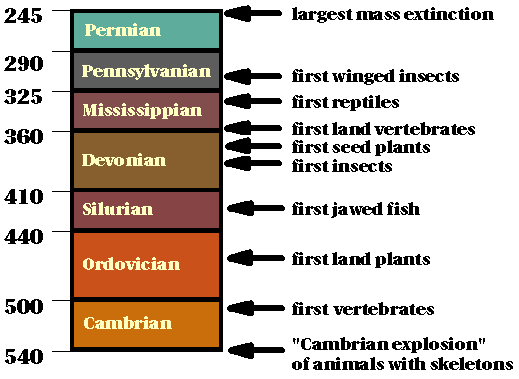

Five hundred million years ago at the dawn of the Ordovician, vertebrates had just developed. By the time it drew to a close around 440 million years ago, plants had crept out of the ocean and spread across land for the first time, blanketing the world in green.

The Earth’s rings are a new addition to this picture, proposed in Earth and Planetary Science Letters by paleo-geologists from the University of Monash in Australia.

A microscopic fossil of a sea lily in Everest limestone. Photo: Noel Odell/Augusto Gansser

Meteor rain that lasted 40 million years

A timeline of the Paleozoic Era, with age in millions of years since present. Photo: University of California Museum of Paleontology/UC Berkeley

Somewhere in the middle of the Ordovician Period, meteors pounded the surface of the young Earth at a rate unprecedented since the Solar System’s formation four billion years before.

It’s hard to overstate how dramatic the Ordovician meteor event would have been if anything lived long enough to notice the change. Nothing did. Geologically short events are long enough for living things to evolve, go extinct, and still have time left over. A hypothetically immortal trilobite, however, would have noticed the average number of meteors hitting the warm waters of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean increasing by 100 or even 1,000 times, for 40 million years or so.

We know this because meteorites are rich in minerals like olivine. Olivine occurs far more in asteroids than on Earth. We find astonishing amounts of these minerals, and even some surviving impact craters, in rock from the middle of the Ordovician.

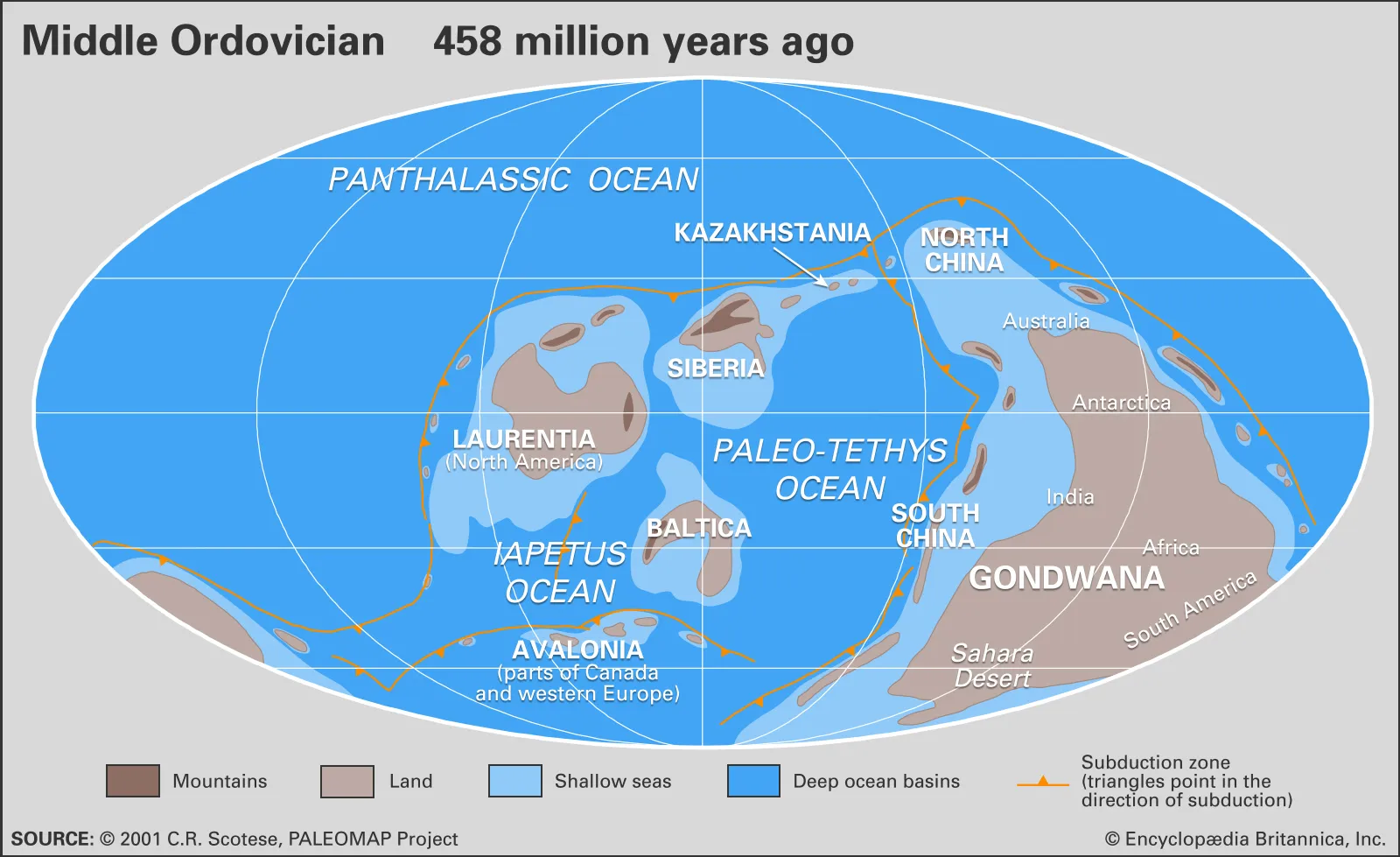

The paleo-geography of the Ordovician Period. Photo: C.R. Scotese/UT Arlington

A new picture of the paleo-sky

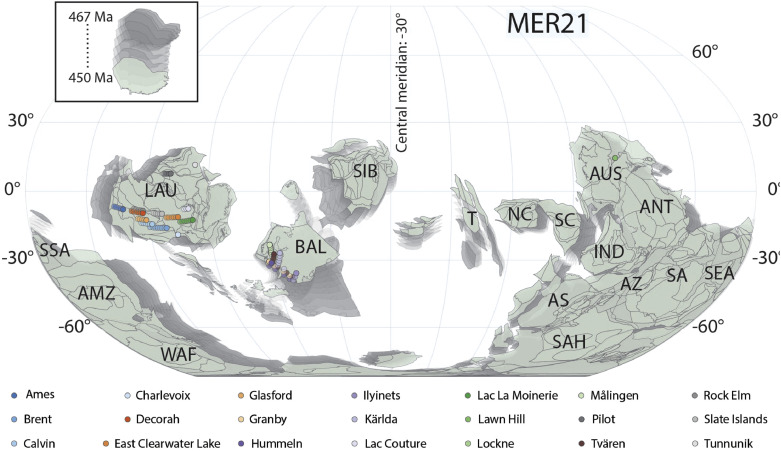

In their new paper, the University of Monash team worked out what the latitudes of the 21 impact craters still visible from the Ordovician meteor event would have been 465 million years ago. They found that not one veered from the equator by more than 30°. Something must have forced meteors to fall around the equator.

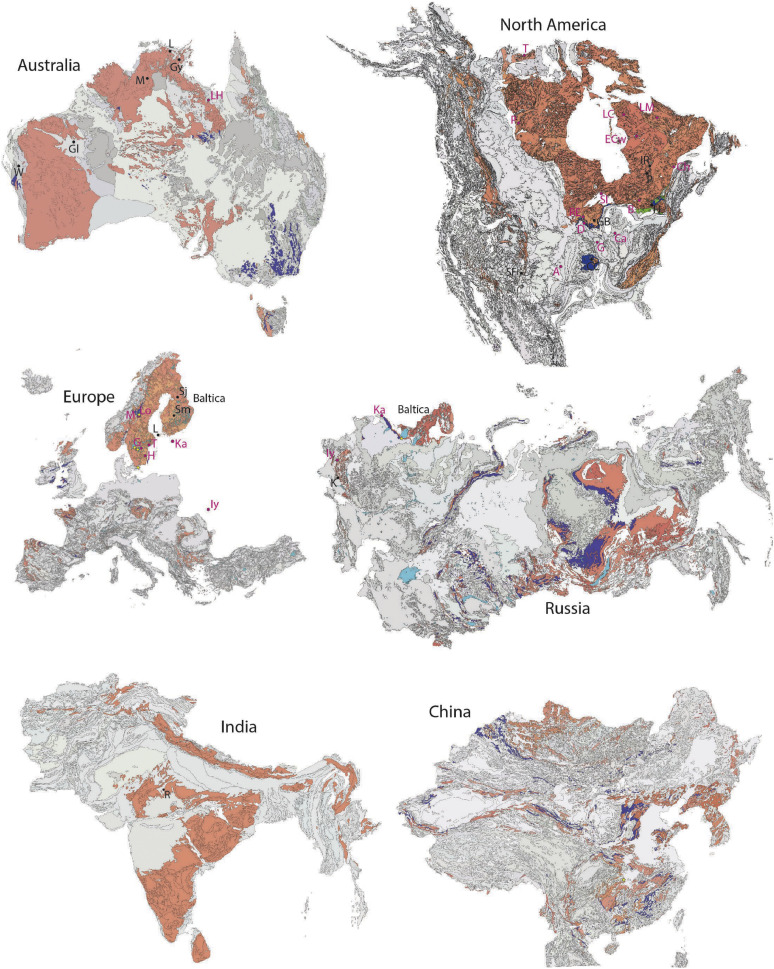

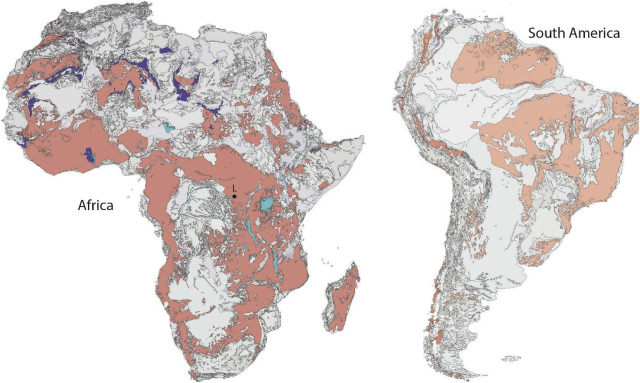

The regions shaded in purplish-blue would have been near the equator in the Ordovician. Older rock is shaded in salmon. Photo: Tomkins et al 2024

The team calculated the probability that meteors from the Asteroid Belt would randomly fall in this region and found that it was one in 400 million. Instead, they propose that a massive object on its way from the Asteroid Belt passed into the Earth’s zone of influence. The Earth’s gravity then tore it apart and bound the remnants in a tight orbit, forming a ring like the ones observed on all the outer planets, including Saturn.

With a ring of asteroids circling the Earth at its equator, it would only have been a matter of time before they all fell to the ground. A matter of 40 million years.

The team’s map of the 21 impact craters with their reconstructed locations on the Ordovician Earth. Photo: Tomkins et al 2024

The icehouse world

In the late Ordovician, winter crept in. This wasn’t a seasonal winter, but a winter no creature would outlive: the onset of an icehouse world.

The Earth goes through cycles of hot and cold. Hot periods, when the earth is known as a greenhouse world, boast luscious jungles at the North and South poles. The cold icehouse periods feature poles capped in ice sheets. We’ve been in an icehouse period for the last 34 million years, and we aren’t due to leave it for millions of years more. That timeline drove climatologists to investigate why our ice caps are melting.

For most of the Ordovician, plants thrived in Antarctica. That changed when the temperature dropped by 8°C and ice crept over the poles. Winters got colder and summers hotter. And yet there was more than ten times as much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere as there is today, puzzling paleo-climatologists. Carbon dioxide retains heat. So how did the temperature in the southern hemisphere drop so suddenly?

The team from the University of Monash propose that the Earth’s rings shaded the southern hemisphere from the Sun, while redirecting more sunlight toward the northern hemisphere. As the debris in the ring finally fell to the ground or escaped the Earth’s gravity, the normal influx of sunlight returned and the poles turned green once more.

The ring was gone, and the Ordovician ended.