What uniquely human staple pre-dates the social conventions of metallurgy, writing, agriculture, or cities?

Until now, conventional thought held that the answer was essentially nothing. But it seems that early hunter-gatherers showed a culinary penchant for more than just hand-to-mouth eating.

As early as 7,900 years ago, our ancient ancestors in Eurasia were busy fabricating and using cookware — and efficiently spreading the know-how to do it. That’s based on a new study that, among other things, used radiocarbon dating to pinpoint the age of nearly 8,000-year-old food residue.

It’s the first time anyone has uncovered significant data suggesting that humans in the area used pottery before agriculture arrived. And it shows that the technique picked up speed a lot faster than previously thought.

An improvement on skin vessels

At first, the region’s hunter-gatherers made containers out of hide and skin. Obviously, such a vessel wouldn’t hold up against fire as well as clay. Neither did wood, which was another early pottery medium. But suddenly, around 5,900 BC, clay pots became the standard from the Ural Mountains to southern Scandinavia.

The sweeping transition, the team found, occurred within just a few centuries. The change suggests aggressive networking between small groups. Because writing didn’t exist yet, word of mouth and direct demonstration would have been the only ways to transmit the requisite technical knowledge. The same goes for recipe books — you can’t cook a meal in a skin bowl the same way you can in an earthenware one, so you’d need all new (primary-sourced) methodologies.

An in-depth look at hunter-gatherers

The study appeared Dec. 22 in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

In it, the researchers combed 156 known hunter-gatherer sites, eventually amassing a collection of 1,491 shards from over 1,000 separate clay pots. To establish a timeline, they used the (somewhat amazing) radiocarbon technique on whatever food bits the dishwasher missed.

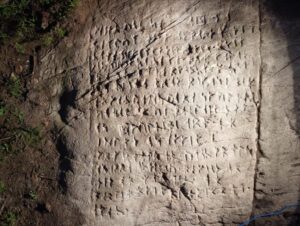

Site map and reconstructions of pottery based on found fragments. Image: Ekaterina Dolbunova et al.

Then, they started examining the artifacts’ shapes and any ornamental patterning they showed. Through that, they developed a map that helped show which populations were sharing pottery with each other.

Fast spread

When they overlaid those results, they found the region’s ancient residents had spread the new technology with remarkable efficiency. Correlating each community against the next one, the researchers found pottery dispersed through Eurasia at about 6-10 kilometers per year. Based on the study’s overall timeline, that’s consistent with the average human lifespan at the time of 20-30 years.

The technology spread rapidly westward, covering over 3,000 kilometers in just a few centuries.

“Knowledge of pottery production was directly transferred between prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies, occurring, for example, through direct contact, migrations or marriage networks,” the study said.

Maybe more intriguingly, the authors also identified a “symbolic” pattern in the habits of the vessels’ creators.

“This discovery, a case of ‘form following function,’ hints at a deeper symbolism employed by the makers of the pots and communicated via some mechanism of cultural transmission throughout the communities,” they wrote.

Limiting factors in the study did exist. The authors noted that the hunter-gatherers’ diets could have affected the findings’ accuracy because animal fats are more resistant to biodegradation than plant fats over time. So, the team’s understanding of exactly what the vessels’ users did with them could be skewed.

They also acknowledged that they don’t think they found the earliest pottery from each site — suggesting that the technology could be even more ancient.