Let’s cut straight to the bad news: you can’t hike to the James Webb Space Telescope. The air’s a bit too thin, and the temperature doesn’t bear mentioning. But while astronomy’s flashiest telescopes orbit the Earth, many on the ground are far more accessible than you might think. We’ve curated a list of observatories to visit that combine stunning natural landscapes with cutting-edge science.

A note: many observatories not on this list feature striking high-altitude vistas. However, observatory boards are understandably reluctant to promote tourism for telescopes that sit at the same altitude as Everest Base Camp. Interested in trekking up to the Atacama Large Millimeter Array in Chile or the Institut de radioastronomie millimétrique in Spain? We salute you, but you’d have to jump through a lot of hoops.

5. Five-Hundred-Meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (Guizhou, China)

FAST in its natural sinkhole, with the mountains of Pingtang County behind it. Photo: Xinhua/Ou Dongqu

China’s radio astronomy community may be young, but it’s thriving. The construction of the world’s largest telescope cemented China’s place in time-domain astronomy — a sub-field focused on detecting and analyzing high-speed events in the sky. These range from supernovae to the mysterious extragalactic signals known as Fast Radio Bursts.

The Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, or FAST, rests in a natural sinkhole in mountainous Guizhou province in southwestern China. Unlike most telescopes, it isn’t steerable. It looks at the same portion of the sky every day. But its massive collecting area maximizes the light it receives from distant sources, allowing it to probe deep into the universe.

Located a 34-minute drive from China’s “astronomy town” of Kedu in Pingtang County, FAST offers all the telescope-based tourism you could want. There’s a planetarium, a room where visitors can simulate changing the active surface of the dish to compensate for the atmosphere, and a viewing platform for the dish itself. The only convenient approach to FAST is by car, but many tourists online complain about the 700+ steps to the mountaintop viewing platform — cementing its place on this list. The weather is temperate and rainy year-round.

4. Palomar Observatory (California, U.S.A.)

An aerial view of Palomar Observatory. Photo: Palomar/Caltech

Most powerful, ground-based telescopes observe at radio wavelengths. Radio waves permeate the Earth’s atmosphere far more easily than more energetic electromagnetic waves such as infrared or optical.

Palomar Observatory is one of two on this list that observe in the optical and infrared, rather than the radio. Its 200-inch telescope was a marvel of engineering when Caltech founder Gregory Hale built it in the 1930s and 1940s. It finally saw “first light” — astronomers’ term for a telescope’s first view of the sky — in 1949. Astronomers still use the Hale 200″ for research.

The view of the 200″ telescope from below, looking up at the closed dome. Photo: Reynier Squillace

But Palomar isn’t on this list just for its foundational place in American astronomy or its charming outreach center. A nine-kilometer trail curls up the mountain through thick forest and culminates at the observatory. The grounds are open to the public, but we also highly recommend taking a tour through the dome and its catwalk, which overlooks the Peninsular Ranges of Southern California.

The view from the catwalk on the outside of the main dome. Photo: Reynier Squillace

3. Parkes Observatory (New South Wales, Australia)

She’s a film star. She’s a key player in the 1969 Moon landing. She’s in the middle of a sheep paddock. Who is she? None other than the 64-meter Murriyang Telescope at Parkes Observatory.

Because of its superior sensitivity, Murriyang relayed most of the Moon landing footage live to a waiting world. The operators continued to point the dish at the Moon through fierce winds that could have toppled the entire telescope. The 2000 Australian comedy-drama The Dish chronicles the escapades of the operators and their NASA liaison.

Located in rolling farmland right next to Goobang National Park, Parkes Observatory offers both scientific excitement and a route of approach via miles of bush trails. Goobang National Park also has camping sites within hiking distance of the observatory. Make sure to pay attention to heat forecasts, though, and bring lots of water.

The 64m Murriyang Telescope at Parkes Observatory. Photo: ATNF/CSIRO

2. Apache Point/Sunspot Solar Observatory (New Mexico, U.S.)

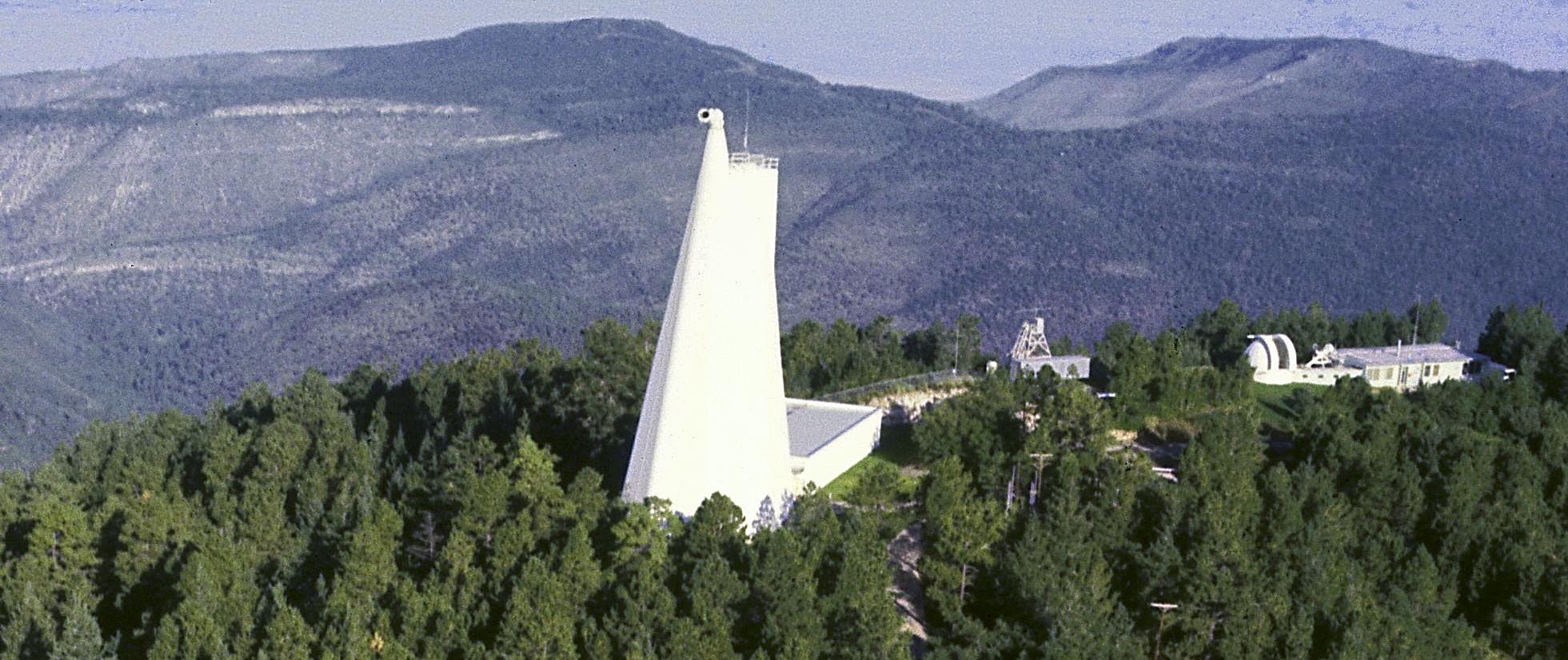

Apache Point Observatory might not be the most powerful telescope out there, but without it, key scientific initiatives would crumble. Perched in the Sacramento Mountains of eastern New Mexico, Apache Point allows self-tours of the grounds. Its neighbor, the unique Sunspot Solar Observatory, boasts a gift shop, a visitor center, and a museum.

Trails run up and down the mountain, linking every telescope with scenic lookouts and smooth running paths. For the most ambitious, a 56km double-track path runs from the nearby city of Cloudcroft all the way up to the observatory. Elk, mountain lions, and bears are common. Bring bear spray and lots of water. Fortunately, the altitude spares the mountain from the worst of the summer heat.

The Sunspot Solar Observatory. Photo: NMSU/NOAO/AURA/NSF

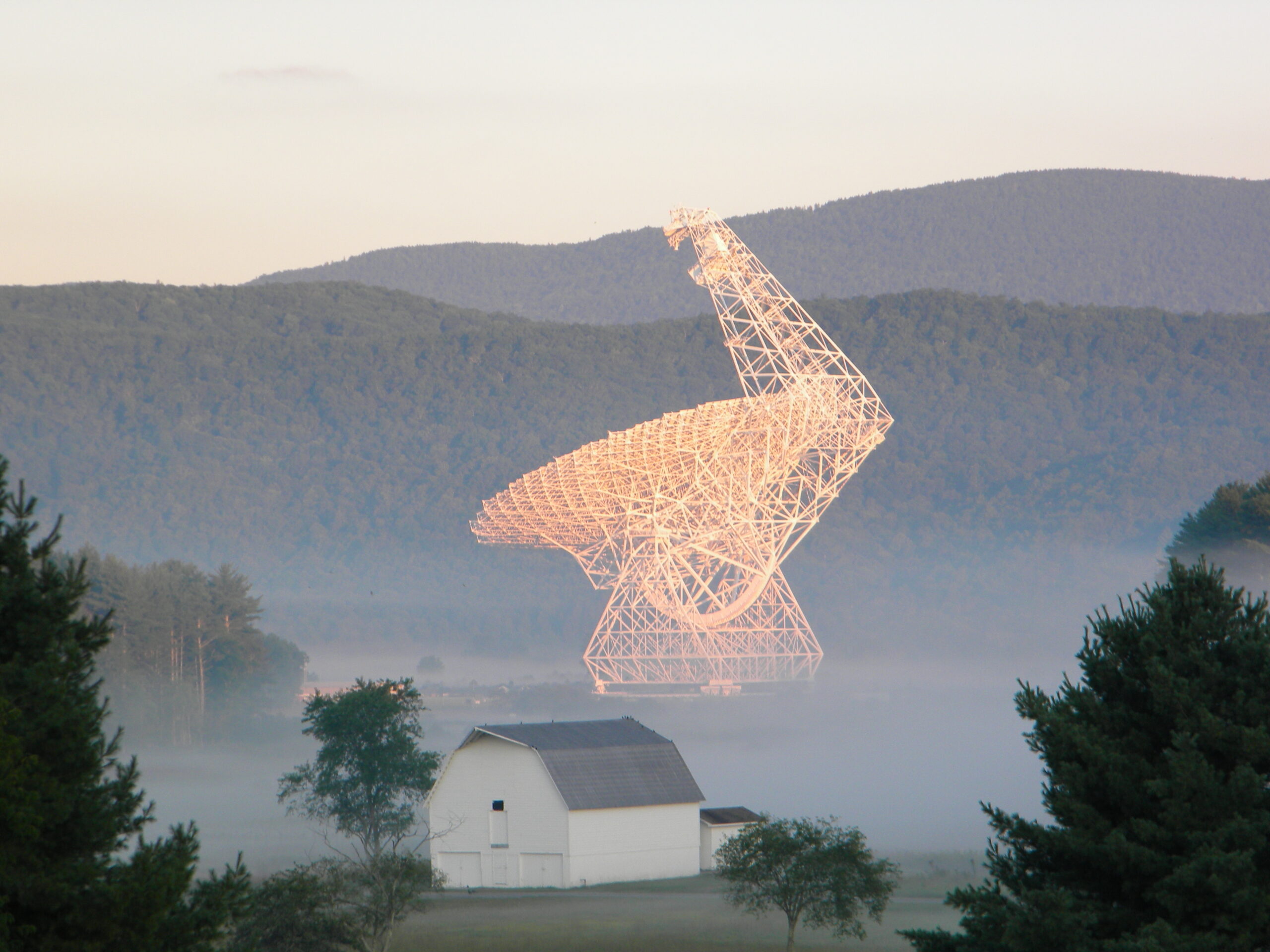

1. Green Bank Observatory (West Virginia, U.S.A.)

Nestled in the Monongahela National Forest without Wi-Fi or cell service, surrounded by fire towers and overlook points, Green Bank Observatory claims first place on this list. Green Bank hosts a staggering variety of radio telescopes, including the largest steerable telescope in the world.

The National Radio Quiet Zone protects the dishes from radio frequency interference — and dramatically shapes daily life in the region. The only phones are landlines, and the only internet is Ethernet. Microwaves on site are kept in iron cages to avoid incidents like the peryton detections of the 2010s, when mysterious signals called “perytons” all turned out to be microwaves in observatory breakrooms.

But if you’re not a radio-noisy electronic device, you can go just about anywhere at Green Bank Observatory. Visitors can walk the five-kilometer loop from the visitors’ center to the 100m dish without any guide or permit. Dogs are welcome. The only fences in place are to stop viewers from standing in the shadow of the dish in case it collapses — again.

Half a dozen trails circle the observatory itself, and yearly trail-running events start or end at the telescope. Countless more paths and camping sites pepper the massive Monongahela National Forest. And if you’re all hiked out by the end of it, we recommend a nice ride on the historic Cass Scenic Railroad.

The 100m Green Bank Telescope. Photo: Dave Curry/NSF/AUI/NRAO

“But what about ____?”

Reasons for exclusion from this list vary dramatically. Some observatories require intense background checks for visitors. Some, like the beautiful Kitt Peak National Observatory, are worth the visit but approachable only by car. In contrast, a 19km trail leads up to Keck Observatory on 4,000m Mauna Kea in Hawaii, but we wouldn’t recommend visiting it due to ongoing tensions between the local community and the observatory over telescope development on sacred land.

Some of the most striking high-altitude observatories, like those on the Atacama Plateau in Chile and in the Sierra Nevada mountains of Spain, welcome visitors but discourage approaches on foot due to altitude-related health concerns.

When we asked staff at several high-altitude observatories about hiking up to the telescopes, they were baffled. What kind of person, they questioned, would possibly want to ascend a mountain on foot?