For over 30 years, starting in the 1940s, hundreds of tons of surplus ammunition was dumped into Lake Mjøsa, Norway’s largest lake. In 2022, a military vessel used an autonomous underwater vehicle to map the dumped bombs. What they found, instead, was a strikingly well-preserved shipwreck.

The sonar image it captured excited marine archaeologist Oyvind Odegard, who was working on the project. But without more information, it was impossible to determine when the ship had been built or what secrets it held.

This grainy sonar image, captured by a military scan, immediately excited researchers. Photo: FFI/NTNU

Exciting find

“This shipwreck is the most exciting find we’ve encountered so far,” said Mjøsa Museum director Arne Julsrud Berg. He has completed nearly two dozen dives in Lake Mjøsa, investigating the remains of 18th and 19th-century ships. But those lay at depths of less than 20m. This one is more than 400m down — too deep for divers.

Instead, researchers from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), led by Oyvind Odegard, sent down a remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV). It was equipped with a grabbing arm and attached to a boat by a long line.

The icy depths presented significant technical challenges on the first expedition in 2023. The robot could only capture a few seconds of video before losing power.

In late 2024, after spending the intervening year ironing out the kinks in their intrepid little robot, they tried again.

While the cold, placid lake bottom preserves sunken ships (and bombs), the surface can be treacherous. Bad weather forced researchers to pull the robot back up before it could collect a sample that would allow them to carbon date the ship.

But they did get incredible photos and video footage of the wreck, which provided researchers with tantalizing clues to its history.

NTNU Researchers Asgeir Sorensen, Geir Johnsen, and Oyvind Odegard stand on their boat with the ROV robot. Photo: NTNU

Meet Storfjorden I

Researchers call the ship Storfjorden I, and thanks to new footage, they now believe it is a type of flat-bottomed vessel called a “føringsbåt.” These were used to carry passengers and cargo across the lakes of Norway for hundreds of years.

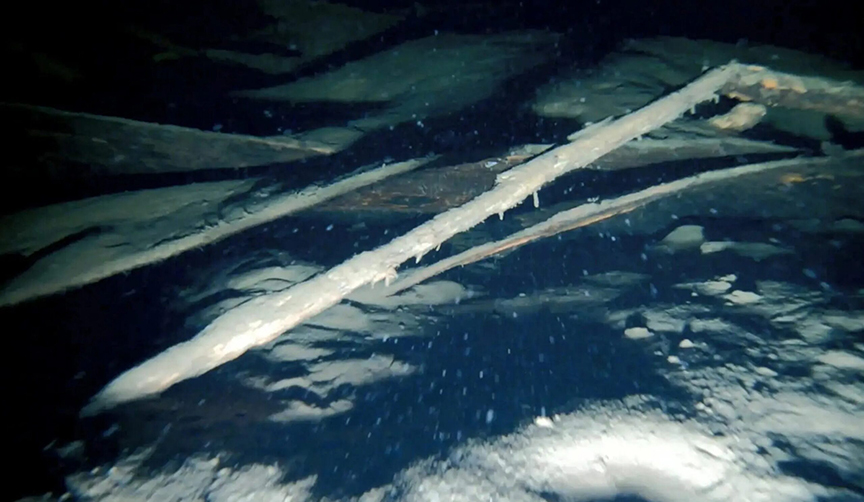

This image of the wreck was one of the few captured in 2023 before the ROV lost power. Photo: NTNU

Viking or Victorian?

Although its name means Big Fiord in Norwegian, Storfjorden — just 10m long — isn’t large enough to be considered a ship. Initial estimates placed Storfjorden anywhere between the 3rd to 4th centuries and 1850. The same conditions which kept the boat intact also make it difficult to date. With a wreck this well-preserved, researchers can’t use the rate of decay to judge its age. So without rot and without a sample, they must use the clues of its construction to narrow down a timespan.

The boat is “clinker” built, meaning the planks are overlaid in the traditional Scandinavian style. Later vessels would be “carvel” built, a style of laying planks down flush that originated in the Mediterranean.

Starting in the late 1700s, the sawed planks for ships came from a shipyard. But these planks were cut thickly with an ax, confirming suspicions that this was an older find. But how much older? Could it date back to the Viking age?

Again, visual clues in the footage provide a tentative answer.

The boat had an upright stern, which in Norway only began around the end of the 14th century. Another hint is how it was steered. Unlike earlier Viking ships, which used a special steering oar over one side of the vessel, this føringsbåt appears to have a central rudder.

But beyond these new ranges, the precise age of the boat still remains to be seen.

The wreck is partially buried in hundreds of years of silt. Photo: NTNU

Future discoveries

Work has only just begun on the bottom of Lake Mjøsa. Odegard and his team plan to go out to the føringsbåt wreck site again next year, and it is likely only the first of many discoveries in the lake.

Another group of NTNU researchers is making a digital map of the lakebed, which integrates satellite, historical, and research data as well as other measurements.

Beneath the surface of Mjøsa, pictured here, countless wrecks may wait to be discovered. Photo: Shutterstock

Lake Mjøsa has been used as a waterway since at least the early medieval era and much of it remains unexplored. In his early years, the great Norwegian polar explorer Otto Sverdrup applied for a job as a ferry captain on Lake Mjøsa.

Sverdrup, who later became the greatest ice navigator of the Golden Age of Polar Exploration, did not get the job because “the company was not willing to take on a man who was unfamiliar with the difficult ice conditions on this lake,” says Sverdrup’s biographer, Per Egil Hegge.