We imagine the ancient world as one made of stone. Marble temples, megalithic structures, and rock-hewn tombs dominate the modern image of the pre-modern period. That image is, of course, an inaccurate one. Stone is all that remains of sites whose flesh was largely made of wood and other fast-decaying plant materials.

This problem of materials is especially relevant to ancient seafaring. Up until the mid-19th century, ships were practically all wood. Worse, the bottom of the oceans tends to be a uniquely bad place to preserve things. Even vessels that sank fairly recently, such as the Titanic and HMS Erebus, are already decaying.

Because of the simple realities of rot, there are very few physical remains of classical-era ships. There is one place, however, where they can be found: the Black Sea.

The face of Helen of Troy is said to have launched a thousand ships. But the wood those ships were made of did not survive the test of time. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Hospitable/Inhospitable Sea

The Black Sea’s unique ecological environment allows it to preserve ancient shipwrecks. Its 436,400 square kilometers fill the space between Asia and Europe, but its secret lies beneath that surface.

Ancient Greeks first called the Black Sea Pontus Axeinus — the Inhospitable Sea. However, as the centuries went on and they established colonies along the coast, they called it Pontus Euxinus, which had the exact opposite meaning from the original name. They couldn’t have known this, but these two contrasting names reflected the hidden duality of the Black Sea.

The top layer of the sea is oxygen-rich and therefore able to support complex marine life. Below 100-200m, however, all oxygen is gone. The Black Sea is the world’s largest meromictic body of water — a marine environment with two stratified layers that never mix.

The two layers exist because water only enters the sea near the surface, from rivers like the Danube and Kuban, and out through the shallow Bosphorus Strait. No water mixing happens below 150m.

Honestly, I was simplifying too much when I said there were only two layers. There are actually secret intermediate layers that keep the upper and bottom from mixing, but for our purposes (shipwrecks) there are two: oxygen-rich upper, anoxic bottom.

That bottom layer is actually most of the sea. Only 13% of the Black Sea is oxygenated. The anoxic layer is a pretty bad place to be alive, but a good place to be a shipwreck.

Phytoplankton blooms seen from space illustrate the flow of water, with the Bosporus on the lower left. Photo: NASA Earth Observatory

A hot spot for shipwrecks

The same currents and tides that wreck ships on the surface can also damage them once they’ve already sunk. Wrecks near rocky coasts are particularly vulnerable and are soon smashed to bits and dispersed.

In addition to those ocean forces, the shipwreck has many natural predators. Organisms like shipworms, gribble (a type of marine isopod), and other wood borers quickly attack exposed beams. Materials buried under sediment will be eaten by bacteria, which feed off sugars like the cellulose and hemicellulose in wood.

So the quiet, deep waters of the Black Sea anoxic zone present an ideal, shipworm-free environment. In 1976, Willard Bascom, an engineer and marine archaeologist, wrote about the possibility of Black Sea anoxic waters preserving a wealth of ancient wrecks.

The Black Sea is also well-situated for wrecking ships in the first place. People have lived along its coasts for tens of thousands of years. Over the centuries, its location between Europe and Asia, connected to the Mediterranean and several major rivers, made the Black Sea a locus of ancient travel and trade.

Its waters were a theater for maritime history, hosting Hittites, Thracians, ancient Greeks, Persians, Scythians, Romans, Byzantines, Huns, ancient Slavic groups, Goths, Vikings, medieval Italian traders, Ottomans, and more.

Technological limitations, however, long prevented investigation of its depths.

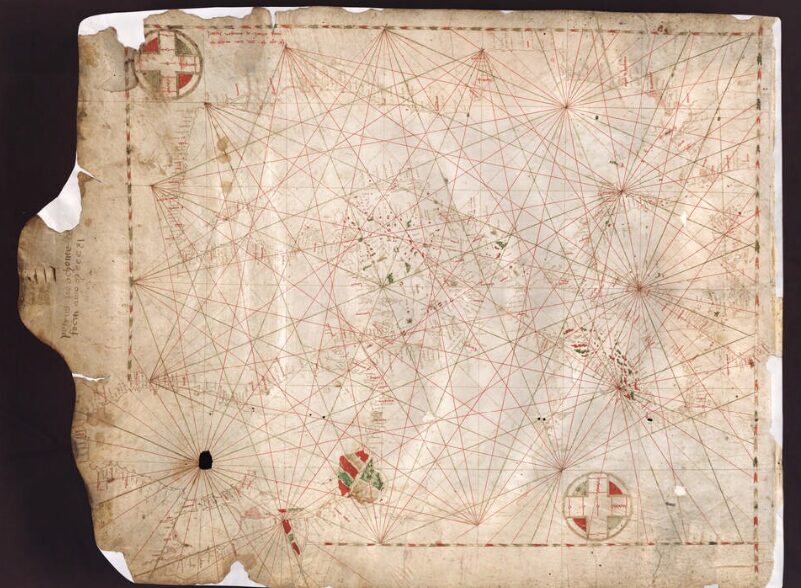

A nautical map of the Black Sea, made by Venetian cartographer Pietro Vesconte in 1311. The area covered in crisscrossing red lines is the sea, and the network of lines is a navigational aid. Photo: Florence, Archivio di Stato di Firenze

Testing the waters

In 2000, Robert Ballard led an expedition to the northeastern Turkic coast of the Black Sea. Ballard pioneered new deep-sea exploration techniques that led him to discover the wreck of the Titanic. Searching off the coast between the Bosphorus and Sinop, the team was also looking for Bronze Age coastal settlements.

The Black Sea Deluge hypothesis proposes that until about the 7th millennium BCE, the Black Sea was a smaller freshwater lake, and people lived on its banks. When the Bosphorus opened, the Mediterranean flowed in, transforming the lake into an inland sea. Finding evidence for this theory was a major goal of Ballard’s expedition.

Using a combination of sonar and remotely operated vehicle (ROV) technology, the 2000 expedition surveyed the sea floor. Argus, a small imaging vehicle equipped with lights to illuminate the ocean floor, was dropped over the side and dragged behind a boat. The other vehicle was remotely operated and attached to Argus. Called the Little Hercules, researchers deployed it to recover objects or samples.

Under 100m of water, researchers traced what they believed to be an ancient shoreline, finding freshwater snail shells and a possible Neolithic settlement, which they named Site 82. Ballard and his team theorized that the regular limestone blocks were the remains of a manmade settlement.

Twenty-five years later, we still aren’t completely sure how the water level in the Black Sea has changed over time. But it probably isn’t as simple or dramatic as the Flood Theory posits. For half a million years, the Black Sea has been repeatedly isolated and connected as water levels fluctuated. But these are gradual processes — there just isn’t a lot of physical evidence for a catastrophic, sudden deluge.

‘Little Hercules’ on a dive in Indonesia. Photo: NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program

But what about the shipwrecks?

Whether Site 82 is a neolithic settlement or just some squarish limestone, it was only one of several key finds. Up to about 85m of depth, years of bottom-net fishing have effectively destroyed the archaeological record. So they began at that depth, scanning a 50km stretch of coast between 85 and 150m.

In a fairly short time, they began getting hits. First, Shipwreck A: two clusters of ceramic vessels and a few half-buried planks, dated to the Late Roman era. Shipwreck B: more ceramic jars and submerged hull planks. The outline of this vessel is larger, and it appears to have a bilge pipe to pump water out of the ship. Based on this, researchers dated it to the Byzantine era. Shipwreck C was similar to Shipwreck A.

Video still, left, and camera image of Shipwreck B. The carrot shaped pottery vessels were common to the Sinop region for centuries. Photo: Ballard et al.

Shipwreck D

The promising findings offered new information on the location of an ancient trade route. But very little remained of the ships themselves; the water wasn’t deep enough to preserve them. Off this coastal shelf, the sea bottom slopes abruptly downward to depths of 1,000m and more.

They turned to the trickier, deeper waters, with little initial success. With the expedition about to end, Ballard and his team made one final sweep — and found something.

Shipwreck D sits upright in 320m of water. It’s remarkably well preserved, with a deck structure, rudder, and mast rising 11m from the hull. There is even cordage wrapped around the top of the mast. Little Hercules collected a sample of the wood from the rudder area. The samples dated to 410-520 AD.

For such an old ship, it was shockingly well preserved, giving archaeologists insight into the construction of Byzantine ships. However, Shipwreck D, now called Sinop D, is most important as a sign of what else could be out there.

While the first three wrecks were reduced to piles of pottery, Shipwreck D had an intact mast, still sticking up. Photo: Ballard et al.

What else was out there?

Ballard and his team returned several times during the 2000s on further expeditions. They continued deploying Argus and Little Hercules to investigate sonar hits.

The technology continually improved, but was still a work in progress. Out of 500 hits, only 44 could be identified, and some of them turned out to be trash. The non-trash spanned a thousand years of history: An early medieval jar wreck, a 19th-century warship, three airplanes and even a WW2 Soviet destroyer, the Dzerzhynsky, named after the founder of the KGB.

Almost 10 years later, The Black Sea Maritime Archaeology Project used its ROVs in the Black Sea. A team from the University of Southampton set out on Stril Explorer, a state-of-the-art offshore survey vessel. They were there for the same ancient coastline debate Ballard investigated in 2000. It was almost by accident that acoustic and sonar data, combined with over 250,000 photographs, allowed them to find, map, and model 65 shipwreck sites.

Hundreds of photographs from multiple cameras were combined to create 3D models of the wrecks. This Ottoman-era trading vessel proudly displays intricate wooden carvings. Photo: EEF, Black Sea MAP

Like the Ottoman ship above, most of them were trade vessels that sank in bad weather. They were far out to sea, along known routes. All were remarkably well preserved. One 13th or 14th-century Venetian vessel was the most complete of its type ever discovered. But the most impressive find was still yet to come.

Medieval Venetian traders used the above vessel, which now lies nearly a kilometer under the surface, with masts and quarterdeck intact. Photo: Black Sea MAP

The world’s oldest intact shipwreck

More than two kilometers under the surface of the Black Sea, off the coast of Bulgaria, lies a ship that is more than 2,400 years old. It was an Ancient Greek trading vessel, loaded up with goods meant for Greek colonies on the coast of the Black Sea.

The anoxic water has done its job; the 23m-long ship has an intact hull, with its precious cargo still hidden inside. The mast stands ready for winds that blew before the birth of Alexander the Great. There are intact benches for rowers who died before the invention of the number zero.

Because the cargo, which would usually be used to date the vessel, was inaccessible, the ROV took a small sample to carbon date. The result confirmed what the ship’s design had suggested: It came from the 4th century BCE.

University of Southampton Archaeology Professor Jon Adams, who led the Black Sea MAP project, was stunned. An intact shipwreck of this age was unheard of. In fact, they could only recognize the ship’s design from depictions on ancient pottery.

“This will change our understanding of shipbuilding and seafaring in the ancient world,” Adams said in a press release.

This find is the world’s oldest known intact shipwreck. Ships have sailed the Black Sea for over 2,400 years, though. Only a small fraction of its depths have been explored, and even older shipwrecks are still waiting to be found.

The ROV hovers over the wreck, lost since the early 4th Century BC. Photo: Pacheco-Ruiz et al