One of the Himalaya’s few remaining “unsolved climbing problems” was ticked off this season, but at a high cost. Marek Holecek and Ondrej Huserka climbed the East Face of Langtang Lirung. The climb took the duo longer than expected, and they advanced beyond the point of exhaustion. The young Huserka never made it back alive.

This climb could have been the top expedition of the year, if not for two terrible questions. Can you consider a climb successful if one of the members loses his life? What level of risk separates the epic from the reckless, and who decides where the line is set?

The aftermath of the climb overshadowed the achievement. On social media, Huserka’s family requested a rescue, while Holecek confirmed the death of his partner. The situation created confusion and unease.

It was only a few days ago that we received a full report and photos from Holecek. helping us to comprehend the magnitude of the climb.

The East Face of Langtang Lirung. Photo: Marek Holecek

A dream of many years

Last September, Holecek told ExplorersWeb he was returning to Nepal to climb “an intact wall of a beautiful mountain.”

“I saw her for the first time in 2004, and since then, she has returned to me in my dreams. So this fall, I’m ending my courtship and going for it,” Holecek said.

As he trekked in the Langtang region, he didn’t explicitly share his plans. However, daily pictures of Langtang Lirung (7,234m), an impressive peak near the Tibetan border, left little room for doubt.

Holecek during the approach trek to Langtang Lirung. Photo: Marek Holecek

Eventually, Holecek announced the route. It would be the East Face, a 2,500m obstacle that had been attempted several times but never completed. The latest to try their luck were Topo Mena, Roberto Morales, and Joshua Jarrin in 2023. That group aborted their summit push because of dangerous rockfall.

Holecek teamed up with two young climbers: Ondrej Huserka and Ondra Mrklovsky. Meanwhile, a friend, Pavel Hodek, planned to wait for them in Base Camp. The team had climbed together before, but it was their first expedition to a big Himalayan face.

During the first two weeks, the trio climbed nearby Naya Kanga for acclimatization and then moved to Base Camp at 4,500m.

The climbers (Holecek on the right) sort out gear at Base Camp. Photo: Czech Expedition Team

First attempt

On October 9, the climbers launched a first attempt that ended quickly in relentless rain that triggered avalanches and rocks plummeting down the face. After a scary night in a tent at the base of the face, the climbers retreated. Ondra Mrklovsky decided there and then that his expedition was over.

Fresh avalanche debris under the East Face of Langtang Lirung. Photo: Marek Holecek

Holecek and Huserka tried again on October 25. They planned for a four-day ascent and two more for the descent. Four days later, they were still far from the summit and struggling.

“Either we reach the summit ridge, which would be nice, or we have one more overnight stay somewhere on a 70° ice slope,” Holecek reported over satellite phone from the wall. Unsurprisingly, they had to endure the second option.

“Tomorrow, we will run to the top and start descending,” Holecek reported. “We are exhausted and still have a long way down ahead of us.”

In fact, it took one more day of hell to reach the top as they struggled to advance in deep snow.

The summit ridge of Langtang Lirung through a telescope. Photo: Ondra Mrklovsky

At the time, no details were available except for some short SMS messages sent by the Czech climber via satellite phone. It is only thanks to the recent trip report that we have a full picture of the climb’s difficulty and the huge level of risk.

The climb, day by day

The complete report, in Holecek’s unique style, can be read here. But here are some highlights.

On the first day, October 25, the pair had to overcome the dangerous sections where avalanches and rockfall had pushed them back previously. They climbed over two vertical walls where the ice was packed in a narrow couloir.

“This entire section was like a dangerous funnel which accumulated material from the vast space above our heads,” said Holecek. “We had to quickly traverse this place to get onto a mixed rock edge, where we hoped to find a place for our first good bivouac.”

The climb was mostly on fragile, foam-like ice where belaying was more “emotional support” than real safety. They also clung to their ice axes as two avalanches swept over them. Finally, they set up their first, very precarious bivouac at 5,500m.

Traverse to the ‘heavenly bridges.’ Photo: Marek Holecek

Progress in the next two days was very slow. The route combined smooth rock and complex mixed sections on unknown terrain. This included a monster traverse to what they called the “heavenly bridges.” These were a difficult section of mixed terrain that forced another bivouac. Their hope that this would lead to an easier snow couloir and then to the summit ridge disappeared soon after. They faced another rock section, the hardest yet.

The third day of the climb on highly difficult terrain. Photo: Marek Holecek

“[On the fourth day,] the difficulties seemed to have no end, and the fatigue began to take its toll,” Holecek wrote.

They spent that day on vertical ice, with increasing wind and no place to bivouac as darkness approached. Thankfully, at the last minute, the climbers found a tiny cave in a vertical ice formation.

Fourth bivouac in a tiny ice cave. Photo: Ondrej Huserka

On the fifth day, the summit looked closer, but progress was still slow. They were utterly exhausted.

“I switched off my brain and only mechanically counted the steps, always a series of six,” Holecek recalled.

The climbers progressed up a seemingly endless ramp of steep, loose snow. At least they managed their first flat bivouac in five days, at 7,100m just below the final summit ridge.

Endless work on loose snow before the summit ridge. Photo: Ondrej Huserka

On October 30, Holecek and Huserka reported that they finally reached the summit at 11 am local time. They took some pictures and started down. And then, silence.

Huserka takes the last few steps to the summit of Langtang Lirung. Photo: Marek Holecek

Huserka, left, and Holecek on the summit of Langtang Lirung. Photo: Marek Holecek

Now we know that the climbers needed two more bivouacs, at 6,300m and 5,500m. On the day after the summit, they had a tense moment while descending among seracs on unstable terrain. It was only when they finally reached the plateau below that they took a breath.

They believed they were past the most dangerous sections. Right after, disaster struck.

Huserka’s selfie during the climb. Photo: Ondrej Huserka

SOS

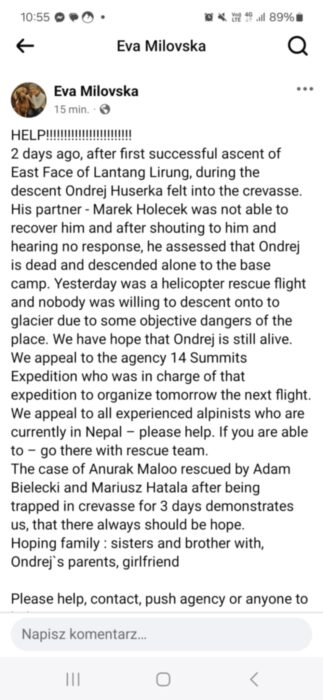

For two days, we waited for news about their descent and arrival in Base Camp. Then, a strange call for help came on November 2.

Ewa Milovska from Huserka’s home team posted an SOS on social media. She reported that Huserka had fallen into a crevasse during the descent. She was asking for help.

The home team hoped Huserka might be alive and, remembering the miraculous rescue of Indian Anurag Maloo from Annapurna one year before, they forwarded the message to Maloo’s rescuer, Adam Bielecki. But Bielecki was not in Nepal.

Bielecki’s home team asked if ExplorersWeb knew anyone who could reach Langtang Lirung’s East Face to try and rescue Huserka.

SOS message from Huserka’s family to Adam Bielecki.

We contacted an elite Ukrainian team on Ama Dablam. They were willing to help but needed to be airlifted from the Khumbu to Langtang.

A rescue attempt?

The East Face of Langtang Lirung. Photo: Marek Holecek

Two other teams were much closer to the accident. One was an Italian team led by Francois Cazzanelli, a mountain rescuer himself. The other featured David Goettler of Germany and Nicolas Hojac of Switzerland, who were in Langtang. All volunteered to help.

The Italian team received the SOS call on the morning of November 1 through the radio in a lodge at Kyangin Gompa village. They were about to leave for their second attempt to nearby Kimshung. Part of their team went to the Czech Base Camp while the expedition photographer scouted the mountain with a drone. They saw a helicopter approaching the glacier, but cloudy weather forced it back.

On the evening of November 1, Marek Holecek arrived at Base Camp and confirmed that Huserka had not made it.

Holecek had followed Huserka into a crevasse, and the younger climber, severely injured, had died in his arms hours later. The Czech team (Holecek, Mrklovsky, and Hodek) was airlifted to Kathmandu on November 2, while Huserka’s team launched the SOS on social media.

That night, Holecek responded with a long text posted on Facebook detailing Huserka’s fall into the crevasse because of a broken Abalakov (a type of belay in ice). He detailed Huserka’s final hours, stating that he died of internal injuries and a broken spine.

“No rescue operation can revive what no longer breathes; disinformation like ‘Let’s save Ondra’ is nonsense,” he bluntly wrote.

In the recent report, Holecek shares more details about the terrible accident, his descent into the crevasse, Huserka’s final hours, and Holecek’s solitary descent.

Ondrej Huserka and Marek Holecek before the final summit push on Langtang Lirung. Photo: Marek Holecek

Painful confusion

It is still unclear why, if Huserka died on October 31, his family still hoped to find him alive on November 2. When accidents happen, informing the climber’s family is an absolute priority. We have no reason to doubt that Holecek reported the passing of his climbing partner the moment he reached Base Camp on November 1 or even before, by satphone.

Huserka was a highly-regarded Slovakian climber. The news of his death caused shock, and the strange way the news was reported only increased the pain.

One of the Nepalese rescuers rappels into the crevasse. Photo: Subin Thakuri

On November 3, the family focused on retrieving the body via a long-line operation. After one failed attempt because of bad weather, four sherpa rescuers and a helicopter pilot retrieved the body from the crevasse on November 7.

A couple of days before, Holecek’s Instagram was full of cheerful pictures celebrating his 50th birthday in a Kathmandu bar.

An Instagram story by Holecek on his birthday, November 6. Photo: Marek Holecek

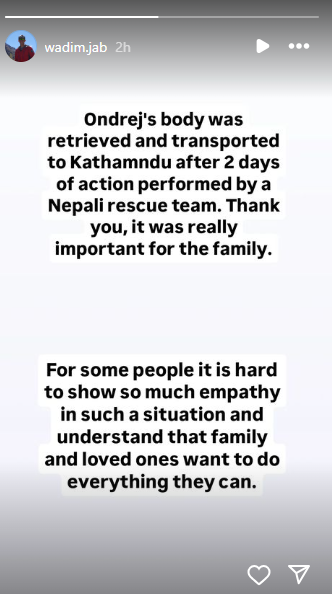

Reactions from Huserka’s friends and family were anything but cheerful. Wadim Jablonski of Poland, who had helped coordinate the rescue efforts, posted the following IG story that day:

Wadim Jablonski’s post on November 7. Photo: Wadim Jablonski

Bitter aftermath

The Slovak Climbing Association (SHS JAMES) was even harsher. In a public statement, it wrote:

When someone dies, we do not celebrate in our culture. We grieve. That is why we were all so deeply affected by the insensitive photos from the celebrations so soon after the incident. We were affected by the disrespect that was presented as respect. We are hurt by the continued lack of humility, compassion, and sensitivity toward the relatives and the victim. This is truly inappropriate. It doesn’t give anyone the much-needed personal peace and quiet to cope with this loss. And yet so little was enough. Ondrej [Huserka] would have really deserved it.

They also raised questions about Huserka’s accident.

“Couldn’t Ondrej [Huserka] have been saved somehow? Had all options been exhausted?” SHS JAMES wrote.

According to Pluska.sk, Holecek said that friends in Nepal threw him a farewell party before leaving on November 4 to cheer him up.

“At that moment, I couldn’t say to them, ‘You know what? Leave me alone!’ I have that sadness inside me, but that’s my personal issue,” Holecek explained.

In another interview on the Blesk podcast, Holecek revealed that Huserka’s family had banned him from attending the funeral.

Holecek’s take

“I will limit myself to saying: it is a shame to waste words,” Holecek finally stated about the media coverage. “The only thing that really saddened me were the expressions of hostility from those people from whom I would have expected more understanding and support, including the opportunity to mutually share the pain over the loss. I believe that time will calm this storm, and the sun will shine again above our heads. Just to repeat some facts: I am the only witness to the events of that unfortunate day. Therefore, the statements can only come from my mouth and written reports.”

Holecek also mentioned the rescue operation to retrieve the body.

“From the very beginning, I did not recommend raising Ondra’s body because of the threat to other lives, and I still insist on this.”

Overshadowed achievement

Each person deals with loss differently. Every life lost on a mountain is a tragedy, and the history of an ascent is invariably affected when someone does not return.

The climbers tackled a face many would not even consider because of its technical difficulty and the objective danger of rockfall and avalanches. Yet the route they opened is incredibly impressive.

Huserka’s accident is not related to the line of the ascent; it happened on the descent, and the climbers were using a different route: “Down a steep ridge and a few passages through seracs,” as Holecek described it.

Holecek summarized the climb as follows:

Ondra [Huserka] and I managed to climb up over two kilometers of a difficult mountain face with a combination of various complicated sections. We succeeded in climbing up and through places untouched by human steps before. We had to endure five rough bivouacs to reach the top of an exceptional mountain on the sixth day of our ascent.

We faced avalanches, falling rock and ice, and other risks. Despite adversity, the journey is accomplished. Ondra and I realized our shared vision, we put all our heart and skills into that ascent. This friendship is bound by the rope and I will always keep the memories of supporting each other on the journey. Only one small move on the descent did not work out for one of us.

Ondra was a perfect fellow, he was an optimistic, smart, and brave guy, a skilled climber with lots of strength and energy. He had the potential to be the leader of a generation of climbers. Heaven decided otherwise. There’s no point in asking why, as there is no answer.

Holecek named the new route Ondrova Hvezda (“Ondra’s Star”). The East Face of Langtang Lirung has finally been climbed. The problem is solved, but the toll is painfully high.

Whether it was worth it or not is impossible to answer.

The new Ondrova Hvezda route and the line of descent. Photo: Marek Holecek