Historians have long wondered why the Black Death took hold when it did and how it spread so rapidly. The bubonic plague tore across Europe from 1347 to 1351, killing an estimated 25 million people. New research suggests that a volcanic eruption was indirectly to blame.

A 1345 eruption threw ash and gas into the air. This created a haze, which caused temperatures to drop for several years. Although fluctuations in annual temperatures are common, low temperatures for three consecutive years are not.

It devastated harvests and triggered widespread crop failures and famine in the Mediterranean. To avoid mass starvation, Italian cities expanded their trade across the Black Sea. Within weeks of the grain’s arrival in 1347 in Venice and other ports, plague outbreaks began.

Researchers think the bacterium that caused the plague, Yersinia pestis, came from fleas on wild rodents (possibly gerbils) in Central Asia. As trade routes expanded, so did the number of Black Sea ships with bacteria-ridden fleas arriving in Europe.

“These powerful Italian city-states had established long-distance trade routes across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea…to prevent starvation,” said Martin Bauch, co-author of the study. “But ultimately, these led to a far bigger catastrophe.”

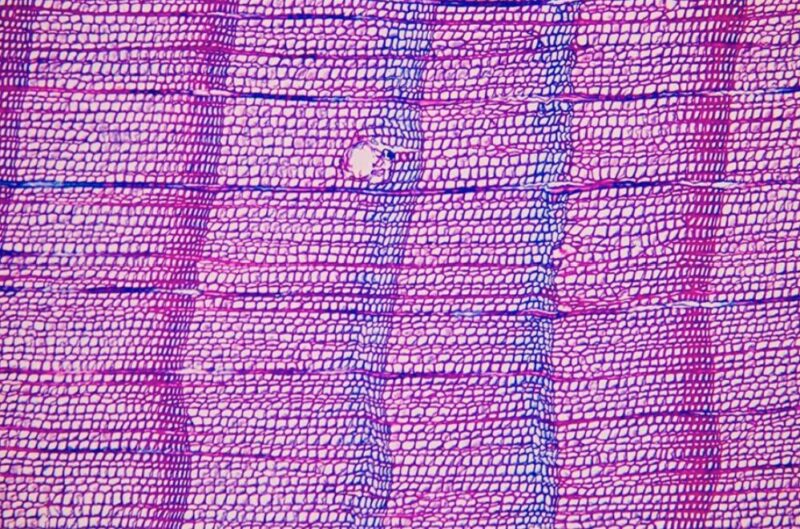

Consecutive ‘blue rings’ in a sample from the Pyrenees. Photo: University of Cambridge

The fleas from the grain ships became the vector that spread the disease across Europe. It quickly passed from rodents and other animals to humans.

Previous research had suggested these expanded trade routes as a possible cause of the pandemic, but this most recent team wanted to shed light on the timing. The bacteria did not suddenly appear in the 14th century; they have been around for nearly 5,000 years. So what suddenly caused its rapid spread?

“This is something I’ve wanted to understand for a long time…Why did it happen at this exact time and place in European history?” said co-author Ulf Buntgen. “It’s such an interesting question, but it’s one no one can answer alone.”

A major clue lay in tree rings from the Spanish Pyrenees. During the summers of 1345, 1346, and 1347, bands of unusually narrow “blue rings” signified cooler, wetter summers. At the same time, ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica reveal elevated levels of sulfur, suggesting a global eruption.

As the sulfur-laden haze blocked the sunlight, it plunged parts of the Mediterranean into colder weather, killing crops and prompting expanded trade. This created the perfect storm for one of the worst pandemics in human history.