Climb in Zion long enough and you’re bound to get waylaid overnight at least once. The huge painted cliffs naturally provoke vertical curiosity, and overstoke is an objective hazard.

So if and when you bite off more Zion climbing than you can chew, you could find yourself devoid of resources and energy, hours from your car or other safe haven once you return to the ground.

From experience, I can say that your proximate goal will be to get to the nearest road. Whatever happens next will be a function of that path — and any other lonely traveler on it.

Let me back up. Dare to Jam fulfills its form as a rock-climbing documentary, sure. Solid vertical action plays out against the backdrop of spectacular desert landscapes in Zion National Park and Indian Creek.

It also does some diligence to stretch the membrane of the category. There’s the “girls trip” trajectory with alpinists Fay Manners and Freja Shannon, and the arch attitude they and many of their fellow Brits hold toward America’s fixation on vehicles.

Photo: Screenshot

The main thrust is that Manners and Shannon, solid alpinists but inexperienced in pure crack climbing, tangle with American sandstone for the first time.

That’s where the reel started to lose me. This story device — “solid climber tries a new discipline and gets stomped” — is so threadbare I can’t make myself patch it back up anymore.

If you’re unfamiliar with the category, have a field day. Dare to Jam‘s two protagonists are candid, gritty, and funny enough to play well on screen. And the flailing is real. (So is the eventual, moderate success.)

But maybe you’ve been around the block before. Maybe you’ve gone out on enough limbs in your day to know that when you do, you’re setting yourself up to dangle in the wind and hold on for dear life.

Maybe the film’s core concept, “new things are hard,” is trite.

In that case, I defy you to enjoy Dare to Jam unless you allow it to hit a special nerve.

Up, down, and out in Zion

For my money and my coincidental personal history, the film’s best moments occur when its protagonists hit rock bottom and a benevolent night-time traveler intervenes.

Minutes into the narrative, we pick up Manners and Shannon tackling Moonlight Buttress, a notorious Zion testpiece. It doesn’t matter what the route is — the only thing that matters is they’re too slow on it.

The soft, smooth Navajo sandstone common in the western United States totally stymies them. As Manners puts it early on, “There seem to be no holds outside of the crack” (sic).

Photo: Screenshot

Their thirst for holds stays unquenched, but they continue up somehow. Hundreds of strenuous vertical feet later, it’s getting dark and cold in Zion. There are times you’re really, really glad you have a jacket.

At exactly 9:49 into the film, I laughed a laugh that finally felt too half-hearted to carry over into the next one. From 9:51 to 9:53, I yawned in unison with Manners.

Photo: Screenshot

View this post on Instagram

When I was a fledgling dirtbag, my friend Nick and I missed the last Zion National Park bus of the night when we got hung up on Iron Messiah. The route was worthy, and it had a soul as black as its black metal name. But none of that mattered — it only mattered that we were too slow on it.

Inexperience reigned, and the climbing was zany. Somewhere in the middle of the wall, I watched Nick throw a passive cam placement into the top of a huge blown-out crack 30 feet above me. It caught nothing but air and rattled ten feet down the inside of the crack until it finally bounced into a tighter spot below. Seconds later, he fell.

We topped out around sundown. The bus would stop running in minutes. Our van was 1,100 vertical feet below and ten miles away. There was a thrilling certainty that society on the ground would soon leave us behind. We cracked open our summit libations. What was the rush? I rolled a cigarette and we shared it.

It was getting cold. We only had one jacket.

We rappelled in the dark. A minor misadventure involving a little dying tree and a crappy old tat forced us to cut both our ropes. But we got down, located the road, took a right turn, and started walking.

We had no more beers. Our walking cadence could be described as determined.

Then a change happened without me exactly noticing it. Laughing suddenly felt like a job. We passed the jacket back and forth with grunts of acknowledgment. Both our phones were dead, and our headlamps soon died, too. It was impossible to tell how many miles to go. I yawned.

But headlights approached from behind.

As the light brightened, engine noise dissipated pleasantly. Somehow I noticed the twinkling stars above.

A vintage Land Rover that seemed very clean pulled up alongside, and the passenger door opened. A blonde driver with very white teeth smiled out at us. We were filthy, and as of this writing, I have no way to tell how bad we must have smelled.

“Need a ride, guys?”

Desert salvation

The driver was Chevonne, a hospitality worker at one of the park hotels. She was from nearby Hurricane (pro tip: pronounce it “hur-a-kun”), born and raised. Yes, this had happened to her plenty of times before. No, not every night. No, it was no problem, she didn’t want any gas money — where are you guys from?

The cabin was heated and luxuriant and after a short interval we arrived at our van, the rest of our beer, and general safety.

Back in Dare to Jam, Shannon and Manners must somehow live to fight another day, too. They finish Moonlight with zero fanfare or even recognition. They rappel, evidently without incident, then pack up and ford the creek.

Photo: Screenshot

They face nothing but a cold dinner of carrots and hummus in an empty parking lot. Their car is “tiny.” A tent awaits, which they describe as “cold.” This is it; the psych is depleted.

But then — headlights in the distance.

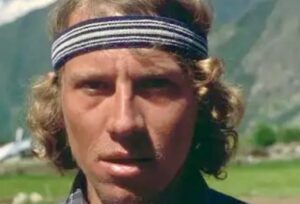

It makes as much sense for you to watch the rest of Dare to Jam as it does for me to describe it. The headlights, of course, belong to the late-night visitor offering sanctuary.

My final gripe about the film is that I can’t tell whether the savior is a stooge in a script or a real live “guardian angel,” which is what Shannon and Manners call him.

Photo: Screenshot

But I don’t really care. Stranger things have happened in the desert. I’ve got my own stories — and Dare to Jam helped me remember one of my favorites.