Five years ago, the mountaineering world watched as disaster unfolded on K2. Three men left Camp 3 for the summit in highly risky conditions, never to return, while a commercial team dealt with failing oxygen, lack of space in the tents, and hours later, a freak fall that took one more life.

The ambitions behind that ill-fated summit push and the subsequent tragedy in part overshadowed the triumph achieved days earlier by a 10-member Nepalese team that reached the summit of K2 in winter for the first time.

K2 in the winter 2020-2021. Photo: Oswald Pereira

Never before had K2 hosted so many winter climbers, all competing to summit the last of the 8,000’ers to be done in the coldest season. The Nepalese succeeded on January 16, but other climbers still on the mountain were not ready to give up.

On the contrary, they raised the stakes even higher. John Snorri of Iceland, Ali Sadpara and his son Sajid of Pakistan [working for Snorri], Juan Pablo Mohr of Chile, and Tamara Lunger of Italy were convinced that, if K2 was going to be climbed in winter, it should be done without supplementary oxygen.

The oxygen question

As far as everyone in Base Camp knew, the strong Nepalese team used oxygen on their ascent. Two days after the ascent, and already at home, summiter Nirmal Purja claimed he had used no oxygen, but nothing changed. The relations between teams on the mountain had been nearly as cold as the temperature, and the Nepalese had built a wall of secrecy around their plans and tactics.

Shortly after returning from the summit, the Nepalese team left in a helicopter to be honored by authorities in Islamabad, then received like heroes in Nepal. Photos of the climb and a summit video were only shared days or even weeks later.

Frame of the viral K2 summit video shared on social media on January 24.

The climbers in Base Camp were unaware, or perhaps not even sure, if the no-O2 claim was real. Not that they cared. Everyone at the foot of the mountain was focused on weather forecasts and hoping for another summit window that would let them summit as well.

The commercial climbers also wanted to try their chances, even those with an obvious lack of experience, despite the fact that this challenge had defeated some of the best Himalayan climbers in history.

Bad omens

What the Nepalese had done was anything but easy. They were extremely strong and experienced, well coordinated and acclimatized, and motivated by ambition and national pride. Last but not least, they were extremely lucky with the weather, as they climbed K2 in winter under excellent conditions.

Mingma David, left, and Gelje Sherpa on the summit of K2. Gelje was the youngest on the team but one of the most experienced, after a previous winter attempt with Alex Txikon. Photo: Gelje Sherpa/Instagram

That rare good weather window never repeated that season. Moreover, on the same morning that the elated Nepalis topped out at last, one member of the group of no-oxygen climbers, Sergi Mingote of Spain, fell to his death between Camp 2 and Camp 1 as he returned to Base Camp from an acclimatization trip.

One of the most experienced climbers in Base Camp, his loss was a blow to everyone and a reminder of how easy it is to die on K2 in winter.

Sergi Mingote, Juan Pablo Mohr, and Tamara Lunger in Camp 1 during the K2 winter expedition. Photo: Tamara Lunger

After days of storm and fierce winds, forecasts finally announced a timid weather window for February 5, although it looked too short for a summit push. But everyone had summit fever, and both no-O2 and O2-supported climbers hurried toward Camp 3. Beyond it lay nothing but ice and cold until the summit.

K2 in winter 2020-21. Photo: Oswald Rodrigo Pereira

The massive summit push

On February 3, most of the commercial climbers went up to Camp 2 (which was divided into two separate groups of tents, to accommodate everyone), as did Jon Snorri and the Sadparas. Meanwhile, Tamara Lunger and Juan Pablo Mohr proceeded up to Camp 3 at 7,000m.

That night, meteorologists confirmed the weather would be good on February 5. This encouraged many climbers in Camp 2 to progress higher. The problem was that there wasn’t enough room for everyone. The Seven Summit Treks leader warned clients to turn back if they did not reach Camp 3 by 1 pm. Some didn’t pay attention. Other climbers begged for room in one of the tents when they reached Camp 3 at sunset. Ensued a sleepless night sitting in crowded tents.

Camp 3 on K2. Photo: Noel Hanna

That night, Tamara Lunger decided to retreat, while Juan Pablo Mohr pushed ahead, together with Snorri and the Sadparas. The following hours were confusing. Some members of the Seven Summit Treks team also tried to leave for the summit, but were soon stopped by what they described as a wide crevasse. Tomaz Rotar of Slovenia told ExplorersWeb he saw no way to cross the crevasse after checking both directions. Other members spoke of oxygen system malfunctions and frostbite.

The Great Serac on upper K2, as seen from the top of the Cesen Route. Photo: Ralf Dujmovits

Across the crevasse

Yet somehow, Snorri, the Sadparas, and Mohr managed to find a way across the crevasse and continued up. Information was sketchy, though Base Camp reported they might have reached the Bottleneck at 8,200m.

Snorri’s tracker then stopped working properly. Some time later, the young Sajid Sadpara, only 19 at the time, returned to Camp 3. His father had told him to use oxygen, but it had stopped working, and Ali told his son to go down.

This saved his life, as the remaining trio — Snorri, Mohr, and Ali Sadpara — were never seen alive again. Sajid remembered a crevasse that took some effort to jump across. He says he did this on the way up and on the way down.

Ali, left, and Sajid Sadpara during the winter K2 expedition. Photo: Sajid Sadpara

The sun rose to a beautiful morning, just like the forecasts had promised, but the commercial Seven Summit Treks team had had enough. One by one, escorted by their Sherpa helpers, they started down. Atanas Skatov was casually walking in front of Lakpa Dendi Sherpa, not yet fixed to a rope, when he suddenly slipped and fell down the Black Pyramid section. There was nothing Lakpa Dendi could do to save his life.

Atanas Skatov in Base Camp. Photo: Atanas Skatov

Sajid waits

At the end of the day, only Sajid remained in Camp 3, waiting for his father, looking up through the night for signs of headlamps. But there was no trace of the climbers.

A rescue operation began the following morning. Chhang Dawa struggled to convince Sajid Sadpara to go down, as bad weather was coming. Two helicopters managed to scout the Abruzzi Spur route despite increasing winds, but found no trace of the climbers.

Meanwhile, Balti climbers Imtiaz and Akbar Sadpara, relatives of Ali and Sajid, volunteered to look on foot. There were two more helicopter searches, with no results. On February 8, the search was called off. The rescuers on the ground refused to leave, but in the end, they couldn’t reach much further, as the fierce winter winds settled in.

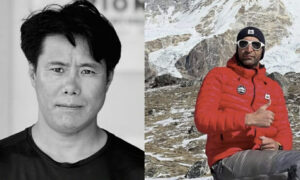

Juan Pablo Mohr, Ali Sadpara, and John Snorri, compiled by Dreamwanderlust

Unanswered questions

The sadness around the death of the three missing climbers was increased by the long, fruitless search, and later, the efforts of their families to locate their remains.

There remained many unanswered questions. What had happened, how had they crossed a supposedly impassable crevasse, how far did they go, did they summit or not?

In the days that followed, some even pointed fingers at the Nepalese team, accusing them of cutting the ropes as they descended from the summit, which they strongly denied. (Besides, the ropes seemed to be in place the following summer.)

For the Pakistan climbing community, the loss of Ali Sadpara, a national hero, was cause for deep mourning. During the winter of 2020-21 on K2, Ali Sadpara was the only one to have summited a winter 8,000’er before. He had made the first winter summit of Nanga Parbat with Alex Txikon and Simone Moro in 2016.

Tribute to the deceased winter K2 climbers on the streets of Skardu. Photo: John Snorri/Facebook

Some of the unanswered questions became clear when climbers the following summer found the bodies. The ropes they were tied to suggested the three had died of exposure while descending, but it was not clear whether they were back from the summit or had retreated at some point. Sajid Sadpara, despite the trauma, returned to the mountain, found the remains of his father, and buried him nearby.

Film to answer questions?

The events that occurred that winter on K2 hit everyone involved hard, even this writer, who followed the events by the hour from the other side of the world. What happened there changed my perception of high-altitude mountaineering, the people who tackled those challenges, their motivations, and their priorities.

Old ropes tangled on K2 during the 2020-21 winter season. Photo: Elia Saikaly

Now, five years have passed. The story of winter K2 is about a climb, but also about human ambition, group dynamics in an extreme environment, and the consequences of our actions. There’s still a lot we don’t know about the last hours of Jon Snorri, Ali Sadpara, and Juan Pablo Mohr.

Many of the climbers on the mountain that day have shared their experiences in a film directed by American Amir Bar-Lev that recently debuted at the Sundance Film Festival. It is called The Last First: Winter K2, and it will soon be available on Apple TV.

This writer was also interviewed at length for the film. We haven’t seen the film yet, so we can’t say whether it has answered any of those remaining questions. But as someone who was involved in the climb has suggested, we should continue to read between the lines.