Denis Urubko and Maria Cardell are in Pakistan to open a new alpine-style route on Nanga Parbat’s Diamir Face. Here, we examine the climbing history of this formidable 4,000m wall.

Nanga Parbat (8,125m) is located in Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan region and has three main faces: the south-facing Rupal Face, the northeast-facing Rakhiot Face, and the northwest-facing Diamir Face. The Diamir Face is bordered by the Diamir Glacier to the west and the Mazeno Ridge to the south, which separates it from the Rupal Face.

The Diamir Face features a complex mix of steep snowfields, icy slopes, rock bands, and couloirs. There are significant avalanche-prone areas and seracs, especially in the lower and mid-sections. It is Nanga Parbat’s most commonly climbed face because of its short approach, established routes, and relatively low (but still significant) avalanche risk compared with the 4,600m Rupal Face or the Rakhiot Face’s long, dangerous glaciers. However, the Diamir Face has other significant hazards, including rockfall and crevasses.

Before the first successful ascent of Nanga Parbat in 1953, dozens of mountaineers had died on the mountain from avalanches and harsh weather. No one topped out until Hermann Buhl’s successful solo summit push via the Rakhiot Face, a story that we’ll revisit on its anniversary on July 3.

The Diamir Face from the air. Photo: Guilhem Vellut

Reconnaissance

In 1932, Willy Merkl’s German-American team explored Nanga Parbat. Though they focused on the Rakhiot Face, they also scouted the Diamir Face and noted its steep ice and rocky bands. In 1934, Merkl’s second expedition again prioritized the Rakhiot Face, but that expedition ended in tragedy when a storm killed Merkl, among others.

Paul Bauer’s German team mapped potential Diamir routes in 1938 while also focusing on the Rakhiot Face. In 1939, Heinrich Harrer and a German team scouted the Diamir Face, concluding it was a viable ascent route, but World War II and their internment in British India halted their plans.

The upper section of Nanga Parbat. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

Mummery’s audacious plan

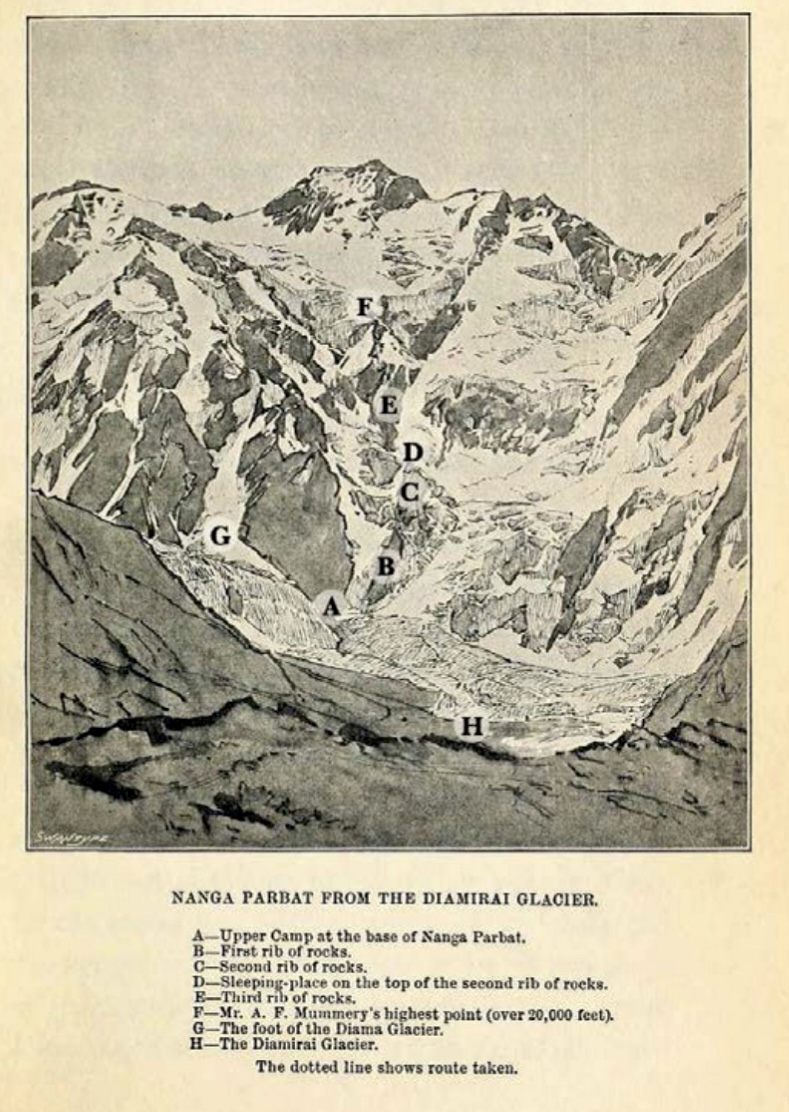

The Diamir Face’s climbing history began in the summer of 1895 with British mountaineer Albert Frederick Mummery and his small team. They aimed to summit Nanga Parbat by the central rib, known now as the Mummery Rib or Mummery Spur. Their expedition was the first recorded attempt to summit an 8,000m peak.

Inspired by earlier reconnaissances in the Karakoram and a desire to test the limits of high-altitude climbing, Mummery formed an audacious plan: He’d climb an 8,000m peak without a large, heavily supported team typical of later Himalayan siege-style expeditions. Mummery’s alpine-style approach was groundbreaking for its minimalism, relying on a small group and limited resources.

Mummery’s team included J. Norman Collie, Geoffrey Hastings, and Gurkha porters Ragobir Thapa and Goman Singh.

Albert Frederick Mummery. Photo: Martin Jacolette

The Mummery Rib attempt

Mummery’s party approached from the Diamir Valley. His strategy was to scout and climb the central rib, a steep rocky feature on the Diamir Face that offered a direct route toward the summit.

Mummery’s expedition reached 6,100m on the Mummery Rib, which was a remarkable achievement for the time, given their lack of supplemental oxygen, primitive equipment, and limited understanding of high-altitude physiology.

At 6,100m, Ragobir began to suffer from severe altitude sickness (likely high-altitude pulmonary edema), which forced the team to abandon their ascent. Mummery, Collie, and Hastings recognized the impossibility of continuing up the technically demanding and exposed Mummery Rib with a sick teammate in deteriorating conditions.

The 1895 attempt on the Mummery Rib. Photo: Montagnes Magazine

A tragic outcome

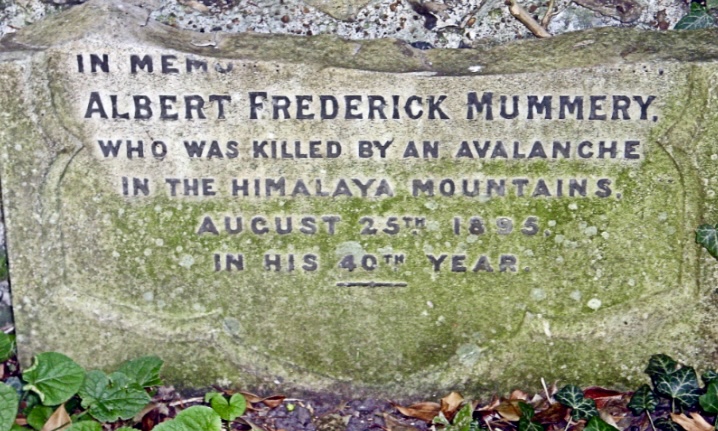

After abandoning the Mummery Rib, Mummery decided to explore an alternative route via the Rakhiot Face, hoping to find a more feasible line to the summit. On Aug. 24, 1895, Mummery, Ragobir, and Goman Singh set out on the Rakhiot Glacier. They were never seen again.

Collie, who remained at a lower camp, later concluded that an avalanche must have swept the trio away while they were crossing a snow-covered pass or glacier. Search parties found no trace of Mummery or the Gurkhas. Devastated by the tragedy, Collie returned to Britain and later wrote about the expedition, emphasizing Mummery’s bold vision and the inherent risks of high-altitude exploration.

After Mummery’s attempt, the exposed Mummery Rib saw little attention for decades. Early Nanga Parbat expeditions focused on the Rakhiot Face, and the Mummery Rib’s steepness and danger deterred climbers for years.

Mummery’s gravestone in St. Peter and Paul Churchyard, Charlton. Photo: Doverhistorian.com

Descending the Diamir Face

In 1970, Reinhold Messner joined a German expedition to Nanga Parbat led by Karl Herrligkoffer. Messner and his brother Gunther climbed the Rupal Face, the steepest and highest rock-and-ice wall in the world, following a new route established by the expedition. They navigated steep icefields, rocky bands, and difficult terrain, reaching the summit on June 27. This marked Messner’s first 8,000m peak and was the first successful ascent of the Rupal Face.

After summiting, worsening weather and exhaustion made descending the Rupal Face too risky. With no fixed ropes or support, the Messner brothers chose to go down the Diamir Face, marking the first traverse of Nanga Parbat (Rupal Face up, Diamir Face down). They followed the Mummery Rib’s lower slopes before improvising a westward path toward the Mazeno Ridge’s lower slopes, crossing gullies and snowfields near the Diamir Glacier. Tragically, Gunther disappeared in this area during the descent, likely swept away by an avalanche. Reinhold barely survived, suffering severe frostbite and losing several toes.

Gunther’s remains, discovered in 2005, reinforced the accuracy of Messner’s earlier account, which had been controversial at the time.

Reinhold Messner, left, and Gunther Messner during the 1970 Nanga Parbat expedition. Photo: Gerhard Baur

Messner’s solo climb

In 1978, Messner returned to Nanga Parbat with a bold goal: to climb an 8,000m peak entirely alone, without support, fixed ropes, or supplemental oxygen.

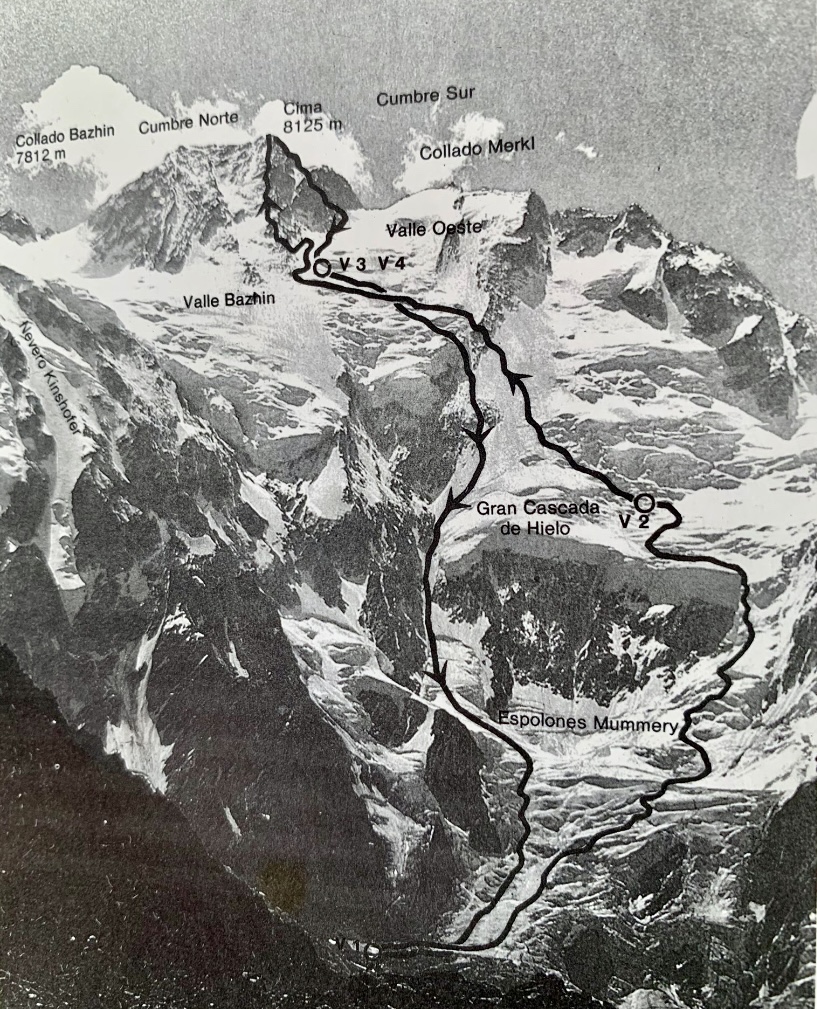

Messner approached via the Diamir Valley and chose a new route on the Diamir Face, starting from Base Camp at 4,200m on July 20. He explicitly avoided the Mummery Rib because of high rockfall risk. Instead, he went further west toward the Mazeno Ridge’s lower slopes, steep icefields, and rocky sections. On August 9, equipped with minimal gear, he reached the summit, completing the first entirely solo ascent of an 8,000m peak.

Messner’s route in 1978. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

For his descent, Messner chose a different route because of avalanche risk. Descending through a steep gully (now called the Messner Couloir) parallel to the Mummery Rib’s left side, he avoided the rib’s rocky spur by staying west and crossing adjacent snowfields and gullies, especially in the lower sections He bivouacked three times during the descent, relying on his experience from the 1970 traverse.

Reinhold Messner alone on the summit of Nanga Parbat in 1978. Photo: Reinhold Messner

A secret solo climb

In the summer of 1999, Hungarian Zsolt Eross ascended Messner’s 1978 descent route. For several years, Eross’s climb was not widely known.

It began in July 1999, when four Hungarian mountaineers organized a trek in Pakistan. The team included Zsolt Eross, Andras Foldes, Laszlo Mecs, and Peter Dely. They had no money to obtain permits for an 8,000m peak and did not have proper gear or equipment.

They headed to the Nanga Parbat region with little beyond a tarp for a shelter and a little food they had rationed from the trek. Despite these limitations, they managed to climb 6,608m Ganalo Peak, a subsidiary peak of Nanga Parbat. Then, 31-year-old Eross told his friends that he wanted to explore Messner’s route on Nanga Parbat. Somehow, he persuaded the group to move to the base of the mountain.

The central part of the Diamir Face. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

Climbing without permits, they had to hide from the authorities. This game of cat and mouse prevented them from properly acclimatizing. Nevertheless, Eross began to ascend Messner’s 1978 descent route alone, with practically no rope or gear.

During his ascent, Eross made three bivouacs. His first was on the plateau below Messner’s Couloir at 5,400m, the second was where the route crosses left through the sloping rock barrier, and his third was below the final headwall. On July 18, 1999, Eross topped out despite deep snow on the upper sections.

Zsolt Eross’s ascent route on the Diamir Face. Bivouacs are marked with an “x”. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

From the summit, Eross descended to his highest bivouac and continued down parallel to the Mummery Rib. During the descent, he became lost, fell into a crevasse from which he eventually escaped, and was later swept down 400m by an avalanche. Though he lost 10kg and frostbit his toes, Eross survived the climb.

Zsolt Eross, alone on the summit of Nanga Parbat in 1999. Photo: Zsolt Eross

An incredible achievement, kept secret

Alongside Hermann Buhl (whose climb was partially solo, as Buhl climbed solo from 6,900m to the summit via the Rakhiot Face), Reinhold Messner (1978 Diamir Face), and Krzysztof Wielicki (1996 Kinshofer Route on the Diamir Face), Eross became the fourth person to summit Nanga Parbat solo.

For several years, Eross and his teammates kept the climb a secret, fearing they would be banned from entering Pakistan.

With no permit, Eross’s climb was not officially recognized. However, it was undoubtedly a great solo mountaineering achievement, and his route remains significant for its historical connection to Messner’s route.

Eross’s ascent line (red) and descent line (yellow). Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

Daniele Nardi

Italian Daniele Nardi made multiple attempts on the Mummery Rib, driven by a passion to climb it in winter.

In 2012–13, Nardi and Elisabeth Revol reached 6,400m but retreated in harsh conditions. Nardi tried again in 2013–14 and other winters, aiming to solo the Rib. His fifth attempt in 2019, with British climber Tom Ballard, aimed for a new winter route. They reached about 6,300m by February 24 and dropped out of contact soon after. Their bodies were spotted through a telescope on March 9 by Alex Txikon, ending rescue efforts delayed by weather and regional tensions.

Daniele Nardi descends toward the Diamir Valley after his first attempt on the Mummery Rib. Photo: Elizabeth Revol

No expedition has definitively ascended the entire length of the Mummery Rib to the summit. Its upper sections above 7,000m are unclimbed because of extreme danger. It remains one of mountaineering’s unsolved challenges.

The first ascent of the Diamir Face

The Diamir Face was finally ascended in 1962, when Toni Kinshofer, Siegfried Low, and Anderl Mannhardt climbed a buttress on the left side, now known as the Kinshofer Route. This was the second overall ascent of Nanga Parbat, following Hermann Buhl’s 1953 Rakhiot Face climb.

The 1962 route avoided the avalanche-prone central Diamir Face by ascending a buttress on the left side, reaching the Kinshofer Icefield, and traversing the Bazhin Gap to the summit. Tragically, Low died during the descent, and Kinshofer and Mannhardt suffered severe frostbite.

The Diamir Face of Nanga Parbat. (1) Kinshofer Route (1962, original line). (1a) Line generally followed today. (2) The Messner brothers’ 1970 descent route via Mummery Rib. (3) Messner’s 1978 descent route. (4) Slovenian 2011 ascent to upper southwest ridge. Bivouac sites marked. (5) Messner’s 1978 ascent route. (6) Upper section of 1976 Schell route (climbs Rupal Flank to Mazeno Col). There have been several variants of Schell’s route, e.g. in 1981 by Ronald Naar, who followed a higher traverse line to reach the snowy section of the ridge up and left from the Slovenian high point. Photo: Viki Groselj

The modern normal route and further variations

The Kinshofer Route has become the standard route, with some variations that are minor adjustments to the established line. These variations are not entirely new routes, but adaptations to address specific conditions like rockfall or serac danger.

The current Kinshofer Route (called Kinshofer Line 1a) deviates slightly from the original 1962 route to avoid hazardous sections, particularly around the Kinshofer Icefield and Bazhin Gap.

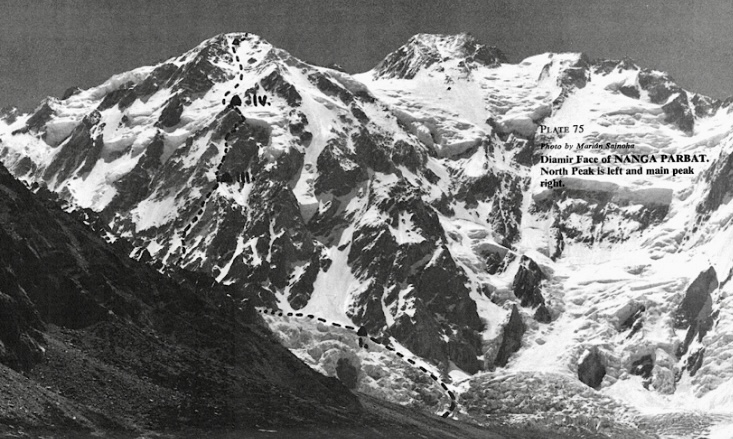

The 1978 Slovak route on the Diamir Face of Nanga Parbat. The North Peak is left, and the main peak is right. Photo: Marian Sajnoha

In the summer of 1978, a team of climbers from Czechoslovakia set their sights on the Diamir Face. The team included Andrej Belica, Joseph Just, Marian Zatko, and Juraj Zatko. They reached the North Summit at 7,800m by a variation of the Kinshofer Route. This ascent, though less celebrated than Reinhold Messner’s solo climb on the face’s right side that same year, was an impressive achievement.

In 2003, Jean-Christophe Lafaille and Simone Moro climbed a new 1,400m line (the “Tom and Martina” route) in alpine style on a broad buttress/spur, left of and parallel to the 1978 Slovak Route. Graded at 90° ice and M6, it later joined the Kinshofer Route. Lafaille continued to the summit via the Kinshofer with Ed Viesturs, whom he met at Camp 3.

In 2022, because of rockfall on the Kinshofer Route, a team led by Mingma G switched to a variation approximating Messner’s 1978 route and established a new Camp 1 at 5,100m. This wasn’t a new route, but a tactical shift to a safer line on the Diamir Face.

Irena Mrak in the Messner Couloir during poor weather in 2011. Left is the Mummery Rib, and up and right, the Messner Serac threatens the ascent. Photo: Mojca Svajger

Slovenians to the upper Mazeno Ridge

In the summer of 2011, two Slovenian women, Mojca Svajger and Irena Mrak, attempted the Diamir Face. They originally aimed for the Kinshofer Route in a classic siege style, without supplementary oxygen or high-altitude porters. However, they switched to an alpine-style ascent beside the Mummery Rib and reached the upper Mazeno Ridge at 7,590m.

On July 24, the Slovenian party established a Base Camp at 4,250m, below the Diamir Face. By August 10, they had acclimatized by reaching 5,800m on the slopes of the Mazeno Ridge and Ganalo Peak. On August 23, the team began their ascent, targeting a direct line on the face to reach the Mazeno Ridge.

They climbed through challenging terrain, including the Messner Couloir, a steep gully with slopes of 45°–60° and a section of 70°. The route was exposed to serac fall, particularly between 4,700m and 5,800m, and included navigating black ice and falling rocks below the Messner Serac.

Irena Mrak at 7,500m in the final gully leading to the upper Southwest (Mazeno) Ridge. Below, flowing northwest, is the rubble-covered Diamir Glacier. Photo: Mojca Svajger

The two climbers reached the crest of the upper Mazeno Ridge at 7,590m on August 23 at 1:30 pm, ascending 3,100m.

“We missed the passage to the summit,” Irena Mrak told ExplorersWeb. “[But] we completed a route to the ridge, spend nine days in the face, and had a severe accident on our return in the Messner/Mummery Couloir. Obviously, we survived.”

The pair reached Base Camp on August 25 after a three-day descent.

While they did not reach the main summit, the Slovenians’ new route was notable for completing a significant portion of the Diamir Face and connecting to the Mazeno Ridge.

Reinhold Messner, commenting on this ascent, said: “The summit isn’t that important. The adventure counts. Eight bivouacs on such a dangerous face is worth more than a few summits by all the prepared normal routes on 8,000m peaks.”

More notable climbs

The Mazeno Ridge was finally fully climbed to the summit in 2012 by Sandy Allan and Rick Allen. They started up the Schell Route to the summit and descended by the Kinshofer Route on the Diamir Face.

In 2022, Francois Cazzanelli and Pietro Picco climbed a 1,400m variant (M6, 90° ice, 85° snow) to 6,000m, joining the Kinshofer Route. Their variation, Aosta Valley Express, included a new start to the Kinshofer Route, not an independent new route.

This month, Urubko and Cardell hope to write a new chapter in the history of Nanga Parbat.

Cazzanelli and Picco’s Aosta Valley Express route in 2022 (marked 2. Their variation included a difficult start to the standard Kinshofer Route. Photo: Viki Groselj