In recent weeks, high profile media have covered Antarctic expeditions involving British adventurer Richard Parks and American Colin O’Brady. In both cases, the journeys and how the adventurers have been presented to a broad audience have drawn scrutiny from the polar expedition community.

Eric Philips, a veteran Antarctic guide and former president of the International Polar Guides Association (IPGA), has raised concerns about the accuracy of media reporting on record claims and professional guiding.

These concerns reflect an effort within the polar community to apply consistent standards when evaluating record claims, an effort formalized through the Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme (PECS).

Richard Parks and the Pole to Pole project

Richard Parks is a British former international rugby player turned endurance athlete. After retiring from professional sport, Parks embarked on a series of high-profile expeditions, including climbing the Seven Summits and skiing the Last Degree to the Geographic North and South Poles.

Most recently, Parks has featured in Pole to Pole, a new National Geographic documentary series that follows actor Will Smith on a 100-day journey to both the North and South Poles while visiting all seven continents. Parks accompanies Smith during the Antarctic leg of the project, where the pair ski a short, unspecified route to the South Pole. Outside Magazine’s coverage presents Parks as Smith’s polar guide.

The series has introduced polar travel to a mainstream audience, but it also raised questions about how the media has presented Parks’ own expedition records and guiding credentials.

Records, terminology, and the role of PECS

Both Outside and National Geographic repeat variants of the claim that Parks is “the first person of color to ski solo, unsupported and unassisted, to the South Pole.” How valid such claims are depends on whom you consult.

Within the polar community, claims are now usually assessed through the Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme (PECS). PECS was developed to address long-standing problems in how polar journeys were described and compared, particularly the inconsistent use of terms such as “unsupported,” “unassisted,” or “solo,” which were often applied loosely or selectively.

PECS provides standardized definitions such as route, distance, mode of travel, and forms of support, allowing expeditions to be compared meaningfully.

Sometimes, these definitions sound like quibbling to a non-outdoor audience, but they were developed because small differences in geography, distance, or travel method affect how noteworthy a polar journey actually is. They exist to preserve historical comparability, not to diminish the effort of adventurers or their personal accomplishment.

Photo: pec-s.com

For example, the term “unassisted” — which originally differentiated between skiing and kiting — had evolved into an extra term added to “unsupported” just to sound good.

“In the end, it only served to give their project some confusingly mysterious gravitas,” said Philips. “Unassisted” has now been largely eliminated from polar expedition language, although it still rears its head from time to time.

Instead, under PECS, journeys are now classified by discipline, such as skiing, snow kiting, or dogsledding, “as ocean travelers differentiate between sailors and rowers,” says Philips.

A polar adventurer hauling their sled on foot in Antarctica. Photo: Henry Worsley

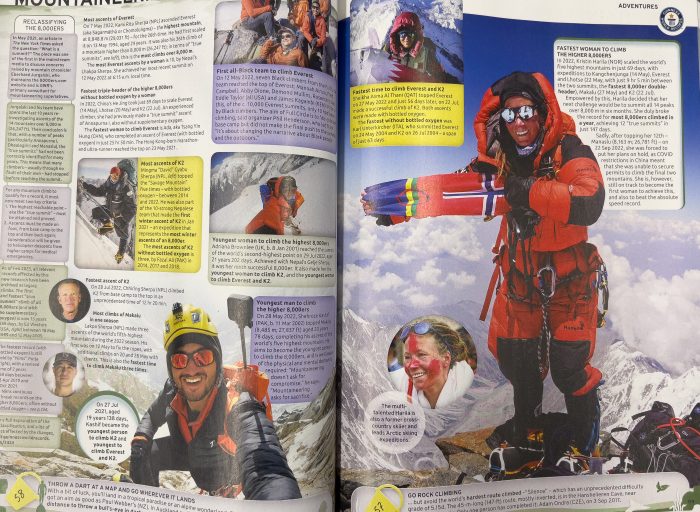

Guinness World Records

Many records cited in mainstream polar coverage, such as Richard Parks’s, are recognized by Guinness World Records, which has been criticized within the adventure community for certifying claims based on narrowly defined or demographic distinctions. Guinness generally validates whether a claim can be documented, rather than whether it represents a meaningful achievement.

By contrast, PECS does not recognize records based on race, ethnicity, nationality, disability, or occupation, focusing instead on the expedition’s objective components.

An excerpt from the 2024 Guinness Book of World Records. Photo: Ash Routen

‘Aggregate distance’?

One of the records cited in the Pole to Pole media coverage of Richard Parks (and recognized by Guinness) is the greatest aggregate distance skied solo and unsupported in Antarctica (3,700km).

According to Guinness, Parks logged this distance over four Antarctic ski expeditions between Hercules Inlet and the South Pole. Two of these were unsuccessful treks in 2013 and 2019, which Parks aborted after 39 and 17 days, respectively. He successfully completed the same journey in 2014 (29 days) and 2020 (28 days), while trying to beat Christian Eide’s old 24-day speed record.

If two of these four journeys were unsuccessful, and the British adventurer twice had to be evacuated by external assistance, it seems a stretch to count them toward some record. At any rate, PECS would not recognize such a claim.

Richard Parks during his unsuccessful attempt to ski from Hercules Inlet to the South Pole in 2018-19. Photograph: Hamish Frost

Tack on extra mileage and call it a record

Another example of a contrived first occurred during the 2023 Antarctic season involving British adventurer Preet Chandi. Chandi set out to ski from Hercules Inlet to the Reedy Glacier on the Ross Ice Shelf, a planned journey of about 1,700km. She reached the South Pole after 57 days.

Although she was by then too late to complete the whole trek, she continued beyond the Pole for a further 12 days before being evacuated. Her team then announced a world record for the “longest solo, unsupported, unassisted [there’s that word again] polar expedition by a woman.”

Lots of women ski to the South Pole; no one skis another couple of hundred kilometers into the emptiness past it. What’s the point? Unless, perhaps, you want to claim some specious record. From a PECS point of view, anyway, her evacuation negates any claims of unsupported.

When is a crossing not a crossing?

A similar pattern has emerged in recent mainstream reporting on Colin O’Brady, including an NBC News segment that frames part of his current Antarctic expedition as historic. O’Brady first gained widespread attention in 2018 for what was widely reported as the first solo, unsupported, and yes, unassisted ski crossing of Antarctica.

While the journey received global media coverage, journalists and polar veterans noted that the route began and ended well inland on the Antarctic landmass and did not include the outer ice shelves — always a part of past Antarctic crossings.

Tractor tracks on a packed, flattened trail beside Colin O’Brady. Photo Colin O’Brady

O’Brady had also skied for hundreds of kilometers on a packed and prepared ice road from the South Pole to the finish line, known as the South Pole Overland Traverse Road (SPOT). This was a form of support because it gave an easier skiing surface and regular markers as navigational aids. Furthermore, all the crevasses are filled in. These issues invalidated his “unsupported” claim in the eyes of the adventure community.

The controversy highlighted the absence of a framework for defining and comparing polar expeditions. In response to a growing number of ambiguously defined firsts, Philips and other polar veterans established the Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme (PECS) in 2021 to reduce confusion and standardize terminology.

A new attempt in 2025-26

In November 2025, O’Brady returned to Antarctica to attempt what he didn’t manage to do last time — a full unsupported solo crossing of the continent, including the ice shelves. This time, he started at the edge of the continent on the Ross Ice Shelf. He is trying to ski to the South Pole and then out to Berkner Island on the other edge of the continent. He is currently 62 days into his journey.

On day 56, O’Brady posted on social media after he had crossed the Ross Ice Shelf: “Just became the first person in history to cross the Ross Ice Shelf, solo, unsupported, and fully human powered.”

“While the Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf in the world, and it has taken O’Brady more than 50 days to cross it, certainly no easy feat, neither his start point nor his route across it, or beyond, is new,” said Philips.

“This was actually done by Borge Ousland in 1997,” Philips continued. “The nuance is that Ousland used kites for part of the distance; O’Brady didn’t…But very few polar aficionados will acknowledge a solo unsupported ski crossing of the Ross Ice Shelf as a significant first, and it won’t be formally recognized by PECS.”

Borge Ousland, the first man to cross Antarctica from coast to coast solo. Photo: Borge Ousland

Philips does point out that “should O’Brady arrive at his planned end point on the other side of Antarctica without support, thus completing his objective of a Full Unsupported Solo Ski Crossing of Antarctica, this will indeed mark a significant juncture in polar history.”

Polar guides

Philips also draws a clear distinction between how professional polar guides operate and how recent coverage has presented the Parks-Smith collaboration. “Parks gives no credit to the actual IPGA polar guide hired for the show,” Philips added.

The International Polar Guides Association (IPGA) is dedicated to the development of professional guiding in the polar regions. It works to standardize skills, practices, and safety qualifications for guides and gives resources to assess guiding competence.

Parks is not an IPGA guide, despite being described as a polar guide by Outside magazine. Within polar circles, the IPGA distinction reflects professional competence. A polar guide is not just a more experienced guy helping a less experienced guy, as Parks did with Will Smith.

Eric Philips guides a Last Degree North Pole expedition. Photo Petter Nyquist

According to the IPGA, becoming a Polar Expedition Guide requires documented experience in long-duration sled-haul travel, outdoor leadership and guiding, glacier/crevasse rescue, firearms, emergency response, and first aid, supported by training records and references.

Philips also notes that IPGA guides present their journeys accurately.

“As former president of IPGA, I’m proud to say that our members project truthful accounts of the journeys they guide, reporting actual distances, verifiable records, ambient air temperatures, and apply transparent labels that summarize the actual journey to onlookers,” he explained.

Why accuracy matters

The distinctions between routes, distances, and modes of travel now exist to allow meaningful comparisons between expeditions. These ensure that significant milestones receive due credit and that misleading claims, amplified by social media and naive reporting, do not gain traction.

When major publications simplify these distinctions to create a more accessible mainstream narrative, they ignore the contributions of adventurers whose genuine accomplishments have advanced the history of polar exploration.