The annals of polar exploration are filled with luminaries who perished too young. Shackleton: dead at 47. Scott: 43. Amundsen: 55.

Though these men passed on far too early, they had enough behind them to leave a lasting impression on the Golden Age of Polar Exploration. Gino Watkins, on the other hand, was barely out of his teens when he vanished off the coast of Greenland in 1932.

Still, Watkins left his mark.

In a career spanning just five years, the young Brit led a 14-man survey expedition to Greenland in support of a future air route from England to Canada, completed a 1,100km open-boat journey around the island’s southern coast, won the prestigious Royal Geographical Society’s (RGS) Founder’s Medal, and may have been the first British person to learn to roll a kayak.

All this before the age of 26.

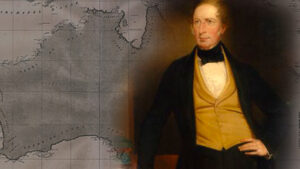

Gino Watkins in an undated, uncredited photograph. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In telling his tale, we marvel at how a thin young child developed into a first-class explorer once mountains entered the mix.

A love affair begins at Chamonix

Henry George “Gino” Watkins entered the world on Jan. 29, 1907. Dartmouth College’s Encyclopedia Arctica lists him as a “fair, lightly built, delicate child” who “showed little aptitude for or interest in athletics of any sort, except shooting.”

As you may know, lightly built children who show little interest in team sports sometimes grow up to be climbers, especially if you take them to Chamonix at the impressionable age of 16. That’s exactly what happened to Watkins (who was already going by Gino, an affectation he retained until his death).

Early exposure to mountaineering in the heart of the Alps is like fitting a key into the lock of a certain type of mind. It kindled Gino’s passion for adventure. After returning to England, the delicate lad spent his subsequent free time climbing in the Lake District. He even notched a 40-climb season in Switzerland that gained him membership in Britain’s prestigious Alpine Club.

Watkins began his higher education at Cambridge with the intention of earning an engineering degree. But fate had other things in store. After attending a guest lecture by geologist and early Antarctic explorer Raymond Priestley, Watkins knew that polar adventures were in his future.

He only had to find a way to make it happen.

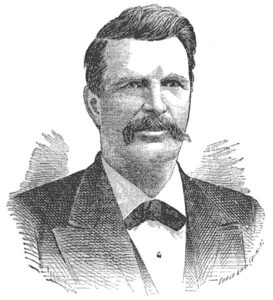

Raymond Priestley (left) and J.M. Wordie (right), two explorers who influenced Gino Watkins early on. Priestley photo: Tewkesbury Museum. Wordie photo: Scott Polar Research Institute.

Self-improvement program

Priestley introduced Watkins to J. M. Wordie, a fellow geologist and veteran of Shackleton’s Endurance expedition. The young man must have impressed Wordie, because the experienced Scot agreed to make a place for Watkins on his upcoming 1927 East Greenland expedition.

Determined to prove his mettle, Watkins spent the next 18 months on a Teddy Rooseveltian program of self-improvement. He trained relentlessly, learned to pilot small aircraft, picked up skiing, read polar literature non-stop, and otherwise developed the jack-of-all-trades skill set needed by the polar explorers of the day.

It wasn’t to be. Wordie’s expedition became delayed indefinitely. But with the kind of cheerful, undaunted perseverance few but 19-year-olds can muster, Watkins proposed to the Royal Geographical Society a scientific expedition — which he would lead — to Edge Island, a Norwegian island in the Svalbard archipelago. The RGS agreed and partially funded the expedition.

Immediately, Watkins organizing the trip with characteristic zeal.

Sea ice with Edgeøya (Edge Island) in the background. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Only five days of decent weather occurred during the month-long expedition. Still, the team — comprising eight men in the primary scientific group, all of whom were older than Watkins — collected enough geological, glaciological, botanical, and ornithological data to warrant publication in a leading journal of the time.

The expedition’s success allowed Watkins to secure RGS funding for future expeditions, one of which would cement his name in the record books of polar exploration.

Labrador and beyond

At the time, much of the Canadian peninsula of Labrador remained unmapped, something the RGS and Watkins were jointly hoping to correct. The plan was to explore good portions of the region’s complicated waterways and lakes using canoes.

The extent of Watkins’ previous experience as a canoeist is unknown, but he likely picked up some paddling skills from both First Nations people and the experienced Canadian trapper/scouts who served as guides.

The expedition tested the then-21-year-old’s skills as a leader. One of the scouts, Robert Michelin, injured his foot with an axe while chopping firewood. It forced Watkins to temporarily halt exploration of the “unknown river” they were paddling and reverse the 20-day canoe journey the group had just completed.

After overwintering in the community of Northwest River, Michelin’s foot healed, and the canoe journey recommenced. During the next year, Watkins’ team also used dogsleds and manhauling to conduct their surveys — battling squishy and seemingly endless marshes, biting cold, low rations, and dense vegetation.

It was during one of these interminable sledging excursions that the idea for the British Arctic Air Route Expedition took root in Watkins’ young but increasingly experienced mind.

A path to glory

Epic boat journey

On the above map of southern Greenland, the red line indicates the route of Gino Watkins’ four-man, 1,100km open-boat journey. Image: Google Earth, ExplorersWeb

Tragedy on the ice

The always-restless Watkins next turned his attention to a proposed crossing of Antarctica. But a worldwide depression was in full swing, making fundraising for such an ambitious expedition virtually impossible.

Instead, Watkins ventured to the Arctic once again with the small East Greenland Expedition to continue the survey work begun with the British Arctic Air Route Expedition.

On August 20, Watkins set out alone in his kayak on a hunting trip. When he didn’t return, two other expedition members went out in a motorboat to find him.

Instead, they discovered his capsized kayak bobbing in the ocean and a pair of soaking-wet pants resting on an ice floe. The best guess is that Watkins’ kayak capsized, and he removed his pants to facilitate his swim to shore. His body was never recovered.

Today, Watkins is remembered for his youth, exuberance, and willingness to use cutting-edge methods to facilitate his surveys. Paddler Magazine speculates that he might be the first British person to have adopted the kayak roll. His expeditions, though few in number, were successful from both scientific and safety perspectives. Greenland’s highest mountain range now bears his name, and both the RGS and Scott Polar Research Institute now award memorial grants in his honor.

His death stands as a huge loss for 20th-century exploration. Who knows what achievements the young man might have wracked up in his thirties, forties, or beyond?