In Nepal, there are 86 peaks (including sub-peaks) between 7,000m and 7,999m. While the limelight inevitably falls on the 8,000’ers, interesting stories are not limited to the highest peaks. Some 7,000’ers haven’t been climbed in years, if ever. As part of a new series, we’ll look at some of these. Today, we examine the climbing history of 7,591m Shartse.

Shartse

Shartse lies in the Khumbu Section of the Mahalangur Himal, on the Tibetan border. It is about two kilometers east of Lhotse Shar and 5.4km southeast of Everest. Shartse’s other names are Peak 38 or Shanti Shikhar.

Its prominence is 121m, but that doesn’t mean it is an easy climb. In fact, according to The Himalayan Database, Shartse is still unclimbed. The database records three Shartse expeditions, in 1997, 2003, and 2015.

Shartse and Shartse II, marked with red dots. Photo: Jill Neate

The Russian attempt

The Russian Shanti Shikhar Expedition took place in the spring of 1997. The eight-man team, led by Alexander Yakovenko, didn’t use Sherpas or supplemental oxygen.

The party chose the south ridge. Then, at the start of Lhotse Shar, they moved to the southeast ridge. But the climbers were not acclimatized for an alpine-style ascent and had to fix ropes along their route. After Camp 2 at about 6,200m, they came to a very dangerous section, and their progress slowed below some scary seracs. The weather also slowed them down, since fresh snow fell every afternoon. Eventually, the team retreated from 6,400m on April 25.

Later, some of the team climbed Island Peak and Lhotse. They concluded that the “best route to [Shartse] is via Island Peak. Lhotse Shar ridge to 7,100m and then either continue up the ridge to Lhotse Shar’s east ridge or traverse east somewhere below it.”

Shartse on Google Earth.

The Czech south face attempt

In the autumn of 2003, the Czech Peak 38 Expedition tried the south face of Shartse. Like the Russian team, the Czechs had only eight climbers and went without bottled oxygen. Led by Robin Baum, they approached from Chhukung Village.

The Czechs put up base camp at 5,250m, on Island Peak’s east side on the Lhotse Shar Glacier. Then they progressed toward its west side. Between Camp 1 and Camp 2 (at 5,300m and 5,800m respectively), they faced a difficult rock pillar. After Camp 2, things became even harder. Several avalanches came down from Lhotse Shar.

Three of the party reached 6,160m. Here, they found huge crevasses and more avalanche danger. They knew that their route above Camp 3 would have to continue by the east ridge, but finally, they had to turn around. They had run out of rope and had no ladders to cross the crevasses.

Another important factor led to their retreat. While they were climbing, a Korean team lost members on Lhotse Shar in an avalanche. This psychologically affected the Czechs.

Sunrise lights spindrift blowing off the summit of Shartse. Photo: Stephen Venables

The South Korean expedition of 2015

In the spring of 2015, a South Korean expedition led by Cha Jin-Chol targeted the south side of Shartse. The team consisted of six South Koreans and five Sherpas. However, the expedition never got going because of a strong earthquake that spring.

Shartse II

At 7,459m, Shartse II (also known as Junction Peak) is a secondary summit located 7.2km southeast of Everest and 1.9km east-southeast of Shartse. Like Shartse, it is little visited, with only four expeditions: 1960, 1974, 1984, and 1988.

In the autumn of 1960, a four-man team led by Edmund Hillary approached without bottled oxygen from the Chhukung Valley via the Hardie Col up to 6,300m on the south ridge. They didn’t go further but climbed Ama Dablam, Ombigaichen, and Island Peak instead. They scouted Lhotse Shar and attempted Makalu.

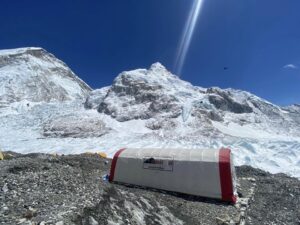

Shartse. Photo: KTM Guide

The first ascent of Shartse II

In the spring of 1974, a German-Austrian team set out to ascend Lhotse by a new route from the Khumbu side. Led by Gerhard Lenser, the team consisted of Hermann Warth, Klaus Peter Bach, and Austria’s Kurt Diemberger, with Sherpas Nawang Tenzing and Sonam Girmi.

Lenser’s team changed its plans because a large Spanish expedition wanted to climb Everest and wanted to be alone in the Khumbu. Today, this would be impossible, but the Nepalese authorities asked the German-Austrian team to shift their objective.

Sunrise on Shartse II. Photo: Mountains Of Travel Photos

With the change, getting to Lhotse would require the team to traverse Shartse and Lhotse Shar. The south ridge of Shartse alone is four kilometers long.

On April 5, after a mammoth 161km approach via the Arun and Barun valleys, the team established base camp on the Upper Barun Glacier at 5,400m.

“The east ridge and the southeast buttress are very steep,” Diemberger wrote.

So in the end, they decided on the south ridge.

The party reached Barun La and then established four camps on the south ridge over the following three weeks. Every afternoon, the weather deteriorated. Yet they managed to fix the route, reaching Camp 4 at 6,500m on May 7. But the harsh storms kept destroying their camps.

On May 18, Diemberger, Warth, and Nawang Tenzing re-climbed the ridge and reached 7,100m on May 22. They stopped to bivouac before the final summit push.

The next day, Warth and Diemberger climbed for 15 hours. They topped out at 1:45 pm, the first ascent of Shartse II. But they were still short of their ultimate goal, Lhotse. “The reconnaissance is completed, good luck to those who go further,” Diemberger wrote.

The view down the Barun Valley from high above Langmale Kharka. Photo: Roger Nix

The second and last ascent of Shartse II

Ten years after the German-Austrian party, in the spring of 1984, a South Korean/Nepali joint expedition climbed the south ridge via the southwest face. On May 26, team leader Lee Yong-Ho reported a sheer ice slope on the southwest face above Camp 2 at 6,100m.

On April 29, after fixing rope along 300m of the ice slope, they put Camp 3 at 6,450m on Shartse II’s main south ridge. Another steep section followed. Yong-Ho described it as a knife-edge ridge.

Eight members of the party started a summit push on May 4, but climber Kim Jung-Ja had to retreat because of exhaustion. On May 7, Dae-Pyo Yoon, Hyo-Kyun Kwak, and Nima Wangchu Sherpa bivouacked at 7,250m. The next day, they summited Shartse II at 11 am.

The three climbers didn’t use supplemental oxygen. Some suffered mild frostbite and one climber fell during the ascent, but nobody was seriously injured.

The party also targeted Nuptse West but gave it up as they had spent too much time and money on Shartse II.

The 1974 and 1984 ascents of Shartse II are the only ascents registered in The Himalayan Database.

The last attempt and tragedy

A small French party led by Erick Bourdais attempted Shartse II in the autumn of 1988. With Jean-Marc Perrot and Jean-Louis LeTrong, Bourdais wanted to ascend by the south col and south ridge. They established base camp at 5,300m at the foot of Island Peak on October 14. They then set up Camp 1 at 5,600m.

Shartse, Shartse II, and Lhotse. Photo: Ramon Munoz

Tragedy struck on October 21. At 6,000m, a serac fell above Bourdais while he was hammering a piton. The avalanche swept Bourdais away. Perrot jumped aside at the last minute before the avalanche reached him.

In The Himalayan Database report, according to the testimony of the two surviving climbers, the seracs didn’t seem threatening before the accident. The party abandoned their attempt after the fatality.